10 magnificent pieces of architecture to visit in Europe

From Roman greats to modern masterpieces, Oliver Bennett takes a closer look at some of the continent’s most awe-inspiring works

Is there such a thing as European architecture? It’s a thorny question at the best of times – and obviously, our current political era can hardly be described in glowing terms.

But as Nikolaus Pevsner’s Outline of European Architecture (1943) noted, there are great architectural threads through time, and his “changing spirits of the changing ages” drew the evolution of European building from Romanesque basilicas through Gothic cathedrals, Renaissance villas and Baroque churches. Much was drawn from the well of Roman and Greek classicism. To which we could add a host of styles and types that crossed borders: Classicism, Gothic, Art Nouveau, Modernism through to the “icon” urinating contests of the last two decades.

There were always tower-height contests and different forces, from Moorish Andalucia to the Renaissance, through the grandiloquent works of Albert Speer, architect of the Third Reich, to Victor Horta, the great Belgian Art Nouveau architect.

Europe’s city-planner architects gave powerful expressions of place, from Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin to Georges-Eugene Haussmann in Paris and Joze Plecnik in Ljubljana.

As Spain-based architect Fabrizio Barozzi once said: “I see European architecture as more of a collage of entities, than of one single identity.” Like Europe’s heterogeneous social composition, that’s just how it goes – the continent remains a huge laboratory.

Architects pick their favourite European buildings

Paul Monaghan (Allford Hall Monaghan Morris)

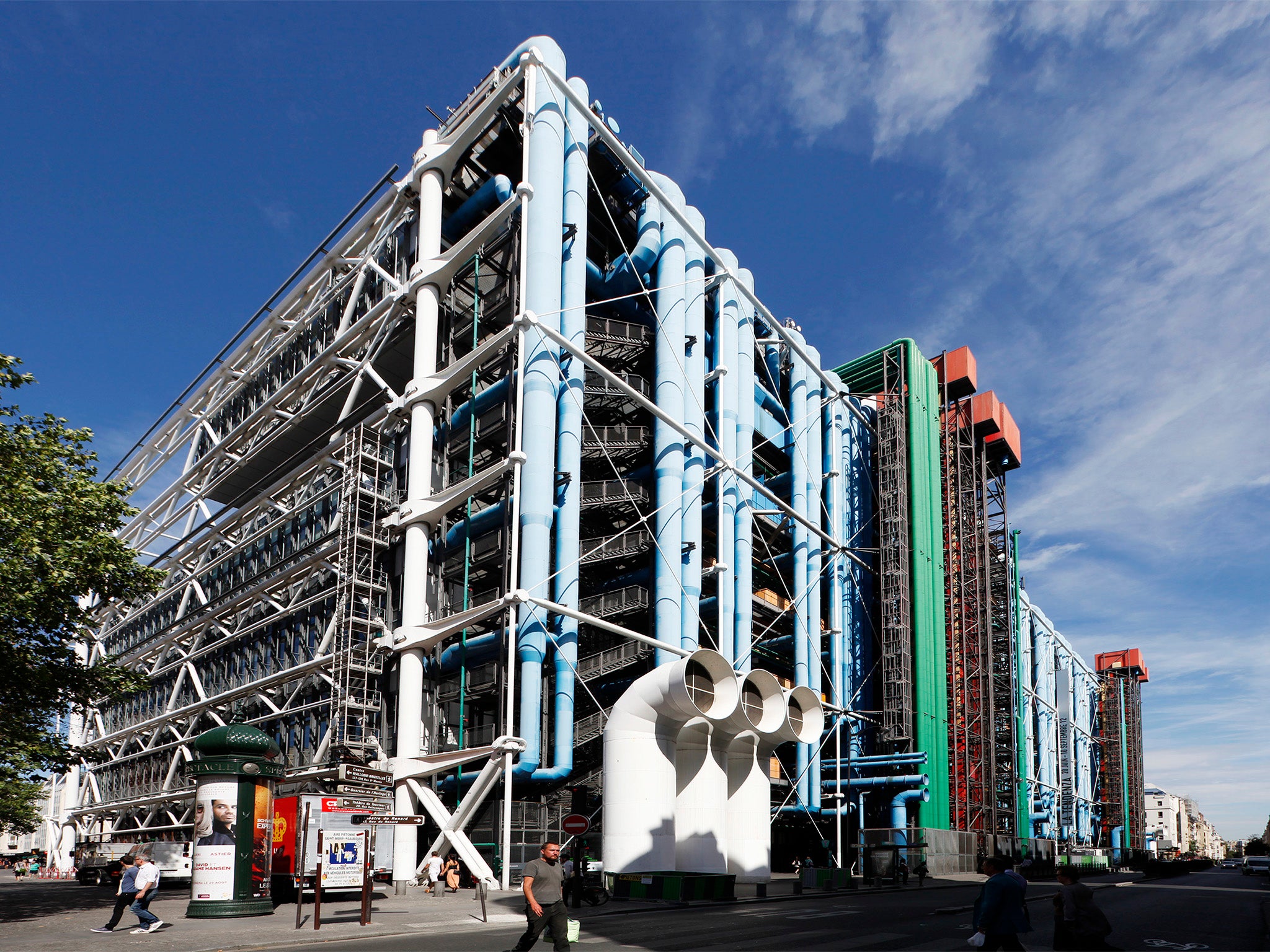

“My favourite European building has to be the Pompidou Centre. It was so radical when it was built 40 years ago and still is today. I first saw it when I was 19 and it made me realise that public buildings could be optimistic and forward-looking. The long rear elevation with coloured ductwork is a real triumph while the civic elevation with its cascading elevators, always full of people, shows that visionary architecture can be both populist and challenging.”

Alison Brooks (Alison Brooks Architects)

“The Staatsbibliothek [State Library] in Berlin by Hans Scharoun is one of my all-time favourites. It’s an organic, meandering and hugely generous building. It feels like a landscape populated by panoramic mezzanines, powerful columns and integrated, sculptural lighting. It’s civic architecture that makes you feel lucky to be a citizen.”

Chris Wilkinson (WilkinsonEyre)

“My favourite European building is the Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe constructed in 1929 for the International Exposition in Spain. It was one of the first buildings to integrate the inside and outside spaces using vertical and horizontal planes. It is beautifully crafted with travertine stone walls and the roof is supported with cruciform steel columns finished in chromium.”

Paul Williams (director at Stanton Williams)

“Many buildings move me, but none quite like Carlo Scarpa’s Castelvecchio Museum in Verona, Italy. Scarpa’s reworking of a 14th-century castle (in 1959-73) balances new and old, sensitively revealing the history of the original building, at the same time celebrating new contemporary interventions. One of the finest and earliest examples of an architect successfully juxtaposing old and new, and creating something greater than the sum of its parts. This project remains an ever-present inspiration today.”

Rab Bennetts (director at Bennetts Associates)

“Palladio’s powerfully elegant Basilica in Vicenza, still the focal point of the city nearly 500 years after it was built, is as European as the cafes and communal meeting spaces it accommodates.”

Fernsehturm, 1965-69, Fritz Dieter, Gunter Franke and Werner Ahrendt (Berlin, Germany)

The Soviets just loved their television towers, and this is perhaps the finest. Built by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) during the Cold War, at 368m it’s the tallest structure in Germany, gazing far over Berlin. Now subsumed by the trend for ‘ostalgie’, the recherche affection for Communism’s past, you can dine in its revolving restaurant Telecafe. But in winter you can still sense the all-seeing eye of the GDR.

Chapel of the Rosary, 1948-1951, Henri Matisse (Vence, France)

In a back street of a pleasant town, this chapel is the masterpiece of artist Henri Matisse. At the ripe old age of 77, Matisse created it for a chapter of Dominican nuns, including his nurse and muse Monique Bourgeois. And if the whitewashed exterior is lovely, then the interior is divine: yellow, green and blue stained glass contrasting with black and white ceramic murals. It took an atheist to make one of the loveliest buildings in the world.

Finlandia Hall 1967-71, Alvar Aalto (Helsinki, Finland)

A discreet grandeur pervades the Finlandia Hall – a congress and event venue in central Helsinki. Aalto designed everything from the doors to tiles, and it has a lovely position by Toolonlahti Bay in this archipelago city. With long horizontals and just-so details – not to mention a restaurant and concert hall – the Finlandia Hall is a kind of meditation in itself.

Alhambra, 889, (Granada, Spain)

The Alhambra started as a fort in the Moorish occupation of Spain. When the Reconquista happened, it changed – apart, that is, from the courtyard, fountains and gardens. It’s a world-class wonder for a relatively small city and almost didn’t survive the 18th and 19th centuries. Now Unesco-listed and with the Museo de Bellas Artes and the Museo de la Alhambra within, the whole site is a delight. Or as author Washington Irving put it: “How unworthy is my scribbling of the place?”

Druzhba Holiday Centre, 1984, Igor Vasilevsky (Yalta, Crimea)

The James Bond baddie school of architecture. This cylindrical holiday centre on the Black Sea has that Cold War space-race aesthetic down pat – indeed, legend has it that in those febrile years, the US thought it was a new and sinister military building. Perched on a hill, and supported by legs and trusses, guests enter via a glass tube. All the rooms are oriented to get a good view, hence that prickly hedgehog look. A late Soviet gem.

Colosseum, 70-80 AD, Vespasian, Titus (Rome, Italy)

It’s hard to think of the huge Roman ovoid without thinking of a swords-and-sandals epic starring say, Charlton Heston – and equally hard to enter it without the clang of sword in the mind’s ear. Yes, the Colosseum really delivers and the Flavian Amphitheatre (as it’s also known) held up to 80,000 spectators, only marginally less than Wembley Stadium. As you clamber over the stalls, remember that they watched executions, classical dramas, animal hunts and battle re-enactments right through to the medieval era. Just watch out for the scammers in plastic centurion helmets outside.

Field of Miracles, 11th century onwards, Bonanno Pisano and others (Pisa, Italy)

It’s thronged, and absurdly touristy, with annoying people taking photographs – and you’re one of them. But it really is worth it. There’s the Cathedral or ‘Duomo’, the Baptistry, the Monumental Cemetery, and of course, the Leaning Tower. The mixture of green grass and the white marble is exquisite, and Pisa itself straddles the Arno river like a dreamscape (indeed, it’s those riverine marshes that make the ground unstable and caused that fateful lean). Come on a winter morning, avoid the tat and you’ll see a dreamscape – yes, it is miraculous.

Pompidou Centre, 1977, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers (Paris, France)

When the Pompidou Centre opened in 1977, it was startling – particularly its escalators, which ran outside the building. The Italo-British duo of Piano and Rogers won a competition with their colourful ‘inside-out’ boiler house: so celebrated was it that Rogers was parodied in satire series ‘Spitting Image’ with his intestines outside his body. The Pompidou exceeded expectations, and with a ‘multi-disciplinary’ ethos and a space outside full of inter-railing students, it changed the face of the modern art museum and ushered in the era of the artistic “icon”.

Sagrada Familia, 1882 onwards, Antoni Gaudi (Barcelona, Spain)

This eccentric architect is Barcelona’s great mascot and Templo Expiatorio de la Sagrada Familia, his masterpiece. Towering over Barcelona, it’s the exemplar of Gaudi’s sinewy Gothic-meets-Art Nouveau style: utterly impressive and vertiginous. Amazingly, it’s due to be finished in 2026, 100 years after Gaudi’s death, when it will have six full spires, topping out at 172m and making it the tallest church building in the world. Consecrated by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010, it should be part of a great double visit to another Gaudi highlight, Park Guell.

Rietveld Schroder House, 1924, Gerrit Rietveld (Utrecht, Netherlands)

The best thing about this primary-coloured, cubic house is that it’s so unexpected, tucked away in a side street in Utrecht. Built by Rietveld for a female client, his big idea was to design it without walls so that one could change it whenever one wanted. By all accounts there was a lot of blood, sweat and tears – and a client-architect affair – but now it’s revered as the domestic expression of the avant-garde art movement De Stijl. If you’re near Utrecht, go – it has a real cranky charm.

Oliver Bennett is the author of ‘Amazing Architecture: A Spotter’s Guide’ (Lonely Planet, £7.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments