Mamas of Africa: How a new female-only expedition is helping empower women in Kenya

Women in Kenya are on a mission to improve gender equality through tourism. Georgia Stephens travels from Nairobi to hear their stories

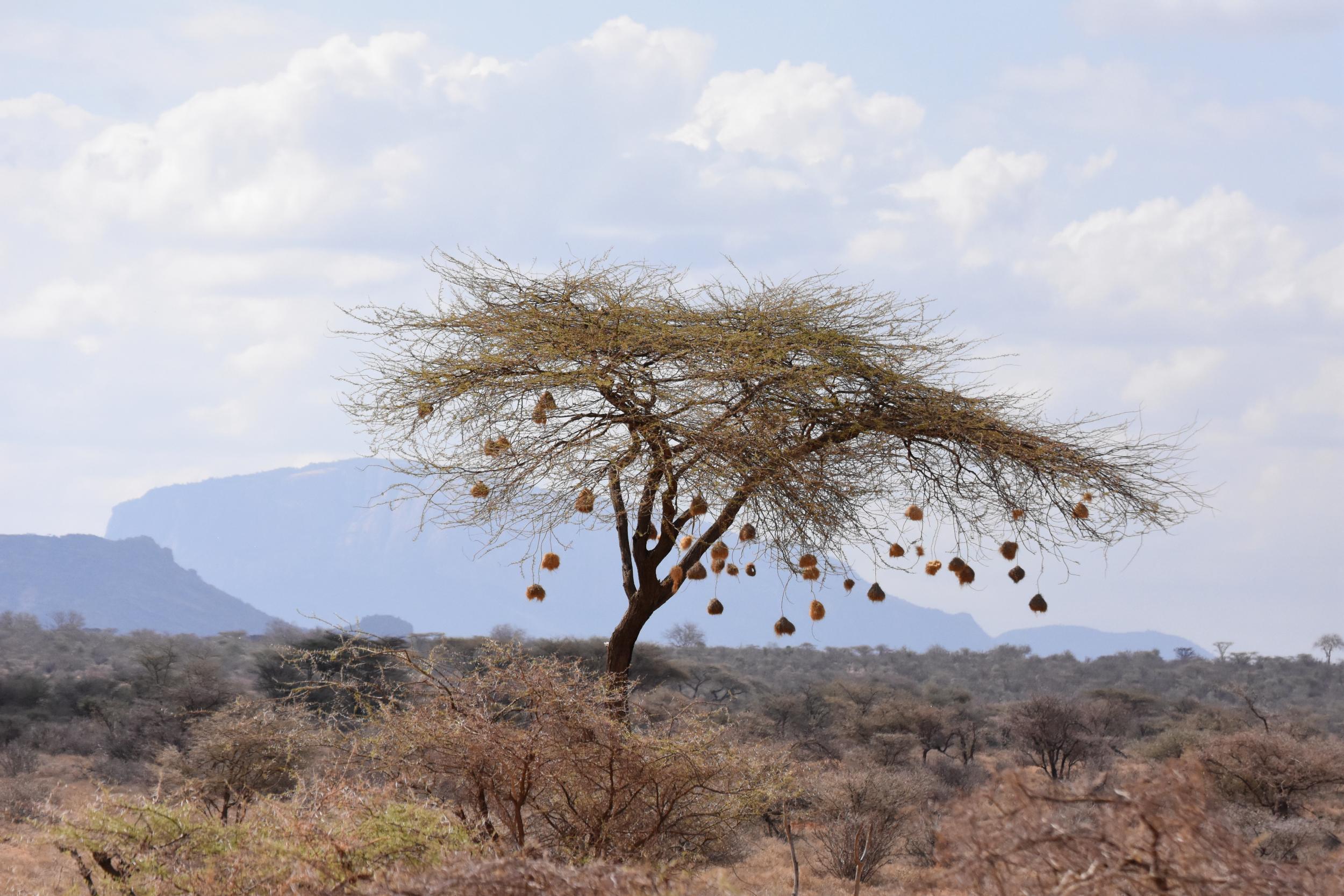

Hold on tight!” comes the warning, too late, as the truck hits a rock and makes a break for the sky. One second, two seconds and bump – we’re back on the dirt road to continue on our rattling way. To my left the scrubland’s tangle of thorn bushes is a blur, vanishing at some far-off point beneath a sweep of umbrella acacias. Hot wafts of baked earth blow in through the truck’s open windows, while up front Becky is shifting gear. The top of her cornrowed head is peeking over the driver’s cab. At 50 years old, she’s east Africa’s first female overland truck driver.

We’re skirting the boundary of the Samburu National Reserve, a protected 64-square-mile sweep of parched semi-desert two hours north of Mount Kenya and a further four hours still from the capital, Nairobi, where our journey began. It’s 38C – this close to the equator, daytime temperatures rarely drop below 30C.

Many who visit Kenya come to see wildlife, to watch nature unfold as it always has here under the rule of tusk and claw. And we will too eventually, once we head south for the plains of the Maasai Mara. But I’m on Intrepid’s inaugural Kenya women’s expedition, and I’m here to listen to the stories of its mamas – that is, the matriarchs of local society. Becky is a mama; these days they call her Mama Overland. But when she first followed in her father’s footsteps to become a driver, she became a controversial figure overnight.

“As a woman, you’re not supposed to do what men do,” she says, casually manoeuvring the truck around a large pothole. “Your job is to give them children and take care of the home: that’s it, that’s all women are for.” Where we are, it’s considered the man’s job to provide protection and tend to the herds of cows, sheep and goats that act as currency in these parts. Women are house builders, they chop firewood and fetch water – but never drive.

“Doing this, I’ve become the talk of my area,” Becky says, suddenly grinning. “But I’m a driver for tourists now, and I’m trying to spread the gospel to young girls that you should never be cheated out of doing what you love.” She slaps the steering wheel for emphasis, saying: “Follow your passion and, let me tell you, you’ll be smiling all the way.”

Women like Becky are sowing the seeds of change in Kenya. In 2017, women were elected to serve as governors and senators for the first time in the country’s history, while a respectable 29 per cent more women ran for office than the previous election. Female-owned businesses are springing up across the country, and women are gradually making a run for those traditionally male roles. And, while progress is slow, things are moving along – in part thanks to the financial support and job opportunities that tourism brings.

We’re off-road now, and Becky is easing the truck to a stop. The doors fold inwards, and immediately the head of a little white goat appears, mirage-like, in the stairway. A herd has surrounded the truck in a skittering mass. And behind, lined up in silence, is a group of women wrapped to the ankles in shades of pink, green and canary yellow, each with a bright beaded necklace hanging stiffly past the shoulders.

We’ve reached Kirish, a community founded to help women who’ve been forced to flee their villages. Some have been cast out for being unable to bear children. Others have lost their husbands to disease or tribal warfare, and been left without an income as a result. In Samburu culture, polygamy is the norm, and it’s common for girls to be married to much older men. Some are widows before they’ve turned 20.

As if there’s been some invisible cue, they start to sing. One by one they strut, birdlike, towards us, their beaded necklaces bobbing with each stride. Abruptly I’m pulled in – an older woman in a zebra-print dress has taken my hand, and we form a circle together with the others for a kind of dance. She’s grinning broadly and nodding approvingly as I awkwardly bounce on the balls of my feet.

The woman in the zebra-print dress is Margaret, mother to six and mama to many. Her head is shaved, and on her ears hang a pair of heavy brass rings – the mark that she was once married. “It’s the older women who guide the group,” Naomi, the project’s coordinator, later tells me. She’s wearing a brilliant green cape tied in a thick knot over a red dress. “Margaret shows the others how to be strong.”

She explains that the women of Kirish are independent, predominantly supporting each other through the beadwork they sell to tourists. They pool their resources, using an initiative called table banking to give each other loans when times are tough. Together, they have learned to be strong. But without the income from tourism, Kirish village would not exist.

Over the next few days we travel 370 miles south to the Maasai Mara via the shore of Lake Naivasha. It’s September and the Great Migration is in full swing, when 1.5 million wildebeest arrive on the plains on a route etched into their DNA. The landscape is green and rolling; it could be Wales were it not for the giraffes.

One morning we rise before dawn for a hot air balloon safari with Lea, one of only two female pilots in the Mara. She learned to fly in a homemade balloon when she was a young girl in Switzerland, and was flying solo by the age of 13.

“I’ve had groups before that haven’t respected women and said they’re not going to fly with me,” she says as we float over a lioness stalking an eland. “So I told them ‘then you stay on the ground!’”

We find our final mama in a village of traditional mud huts in Loita Plains, three hours east of the Mara. Hellen is a formidable figure despite her small stature, a fan of bold beaded jewellery with a booming voice, who’s estimated to be in her fifties. As we stroll the stone-lined paths she gestures widely as she speaks – something she picked up during her time as a school teacher. Years before that, when she was nine, she tells me she suffered female genital mutilation (FGM).

Hellen is a Maasai, a cousin of the Samburu, and in her culture FGM is considered a requirement for a girl to become a woman. Thankfully the harmful practice was made illegal in Kenya in 2011, but it remains prevalent in rural communities. Girls are given a year to recover before they’re married off in exchange for cows. Hellen was traded as an uneducated 11-year-old to a man in his seventies, and was later rescued by a Catholic nun. Now, she’s a champion for Kenyan women’s rights.

“I just said enough is enough: I should fight for the rights of my girls,” she tells me, clenching her fists. In response to her experiences, Hellen founded Enkitenf Lepa School, a rescue centre to educate and protect at-risk girls, which she mostly funds through her eco-camp and other tourism projects. Translated from the Maasai language, it means “Our Cow School”. Hellen’s family have since rejected her, and she’s facing daily resistance from tribal leaders who will oppose change no matter what.

We stop in the shade of an acacia, and she turns to face me, her expression resolute: “All of my girls were supposed to be wives. Now, some are at university. They have grown up with culture in one hand and education in the other.” She pauses thoughtfully. “Change is coming to Kenya, and we will do away with harmful practices – even if it’s one step at a time.”

Travel essentials

Getting there

Intrepid Travel’s 10-day Kenya Women’s Expedition starts from £2,095pp, including accommodation, activities, overland transport, all breakfasts and dinners and six lunches.

More information

British nationals require a visa to enter Kenya, available online at evisa.go.ke or on arrival at the port of entry (£42).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments