‘Collective punishment and imprisonment’: What is life really like inside the Kashmir state lockdown?

The political situation between India and Pakistan has nearly reached boiling point. It’s the people living here who are stuck in the middle, says Rajesh Venugopal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Why have you come here?” asked the policeman in Hindi. He was genuinely puzzled and concerned. It was 5.45pm on a sunny Friday afternoon, and I was the only civilian in the middle of Lal Chowk, Srinagar’s large, iconic central square and shopping district. At what should otherwise have been a busy evening, there were no shops open, no shoppers, pedestrians, cars or buses. A few stray dogs lay fast asleep, undisturbed under the shade of the shuttered shops. Otherwise, it was just me and the 30-odd armed paramilitary police of India's Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) dotted around the square, many holding riot shields and standing alongside long stretches of concertina wire. At one end of the square stood a full military bunker and an armoured vehicle with guns poking out of them – pointing in my direction.

Srinagar, and indeed the entire Kashmir valley of seven million people, is under lockdown and saturated with security forces who have blocked off traffic in large parts of the city. There is also a general strike, called by no one, but observed by everyone, so that virtually all schools, colleges, and shops are closed. The internet and mobile phone networks are dead.

This is the middle of tourist season, but the tourists were ordered out by the government along with most migrant workers a few weeks ago. Srinagar’s beautiful Dal Lake, and its iconic shikaras and houseboats are idle, and there’s a deathly quiet.

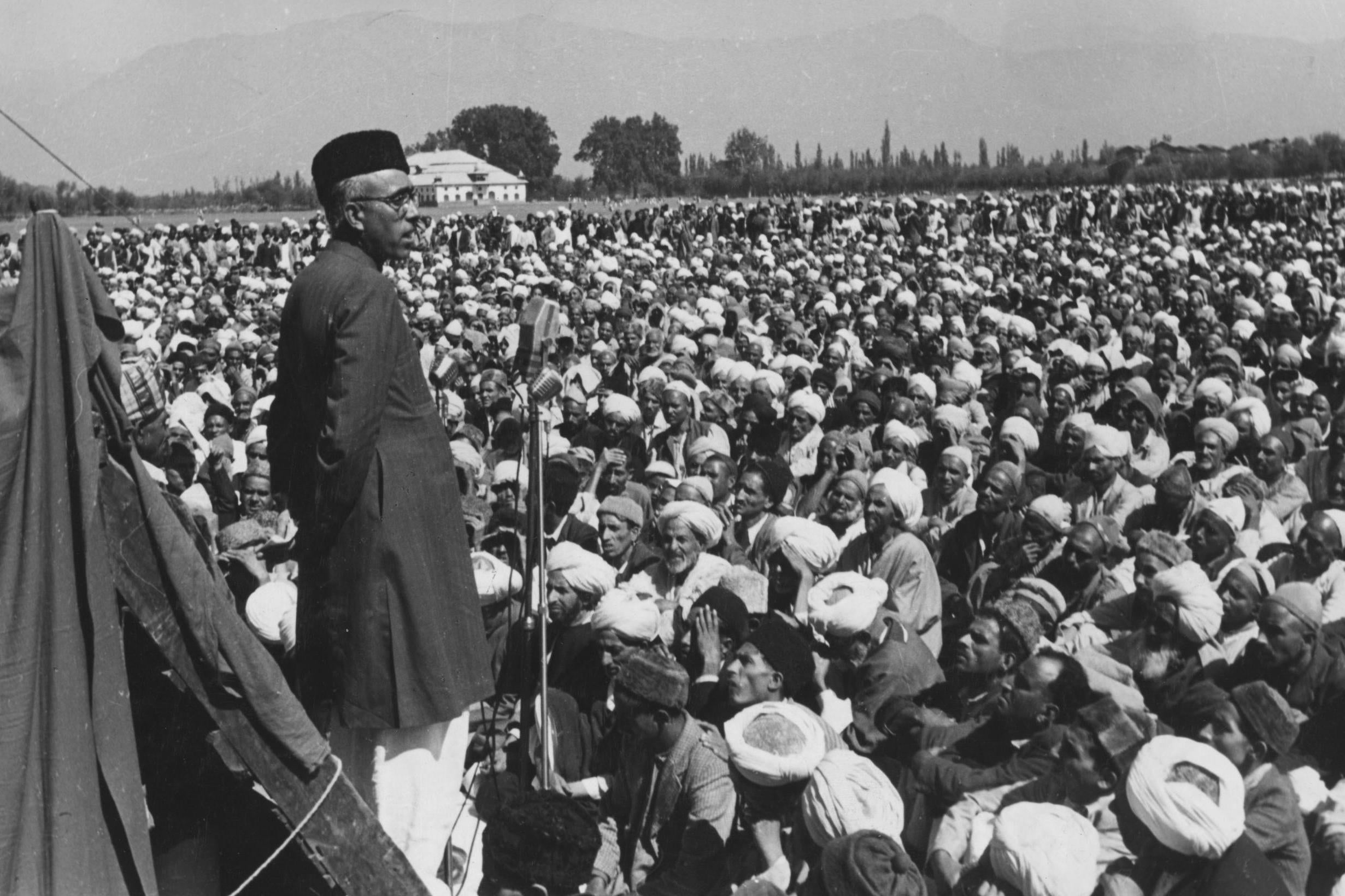

I came to Srinagar two weeks after a constitutional blitzkrieg by India’s Hindu nationalist BJP government that sought to impose a radical new status, and effectively annexe this disputed territory. Kashmir is part of the ‘unfinished business’ of the partition and decolonisation of British India in 1947 – a Muslim majority princely state whose Hindu ruler acceded to independent India rather than Pakistan under the fog of war. In Kashmir valley, which is over 95 per cent Muslim, Indian rule is manifestly resented, and there is widespread support for azaadi (independence), often erupting into street protests, stone-pelting, and strikes that last for days.

From Lal Chowk, I crossed the road, and walked over towards Maisuma, a densely populated neighbourhood that is home to separatist leader Yasin Malik, and which has been a hotbed of street protests. But the entrance to Maisuma was blocked, and the neighbourhood had been turned into a fortress by the police, as have many parts of downtown Srinagar. There are armed paramilitary cops strung out in thick numbers everywhere, in virtually every street, intersection, bridge and flyover. I’ve travelled to many conflict zones over the years, including Jaffna during the civil war, and I’ve never seen anything quite as oppressive and claustrophobic.

I have been off-grid in Srinagar for two days now, but I still keep reaching reflexively for my phone. For everyone else here, it is day 18 of groundhog day. Every day is just like yesterday: there’s nothing to do, nowhere to go, no phones, no internet, no idea when it’ll end, and the security forces are watching suspiciously from every corner. For weeks now, people haven’t been able to speak to relatives abroad or even the rest of India.

They also have little knowledge of what is going on outside, except through the maddening experience of watching Indian TV news, much of which has become part of an embedded, official disinformation campaign. To be fair, this is not true of all the Indian media, but there are a number of toe-curling propagandist English and Hindi news channels that have taken it as their patriotic duty to broadcast sunshine stories about Kashmir that have no bearing with reality: that life is back to normal and getting better every day; Kashmiris have accepted and welcomed their new fate; and that they appreciate the hard work of the security forces in keeping them safe.

New Delhi’s approach to Kashmir, and indeed to the other ethnic separatist insurgencies in sensitive border areas has long been about asserting firm military domination over a hostile population. But beyond the sticks of counter-insurgency, Indian rule always rested on a number of carrots designed to win popular consent, including economic development schemes, political autonomy under local elections, and a special status within India’s federal structure. It is another matter that these provisions are largely formalistic, have been whittled down over the years, and have generated a pliant pro-India political elite who are viewed with scorn by the public.

For long, mainstream Indian political leaders had grudgingly accepted the inevitability of negotiations with Pakistan and the Kashmiris themselves, in order to arrive at a final status agreement. Kashmir is, after all, no ordinary internal insurgency, but the subject of an international dispute, so that leaving aside the instrument of accession signed by the Maharaja, or Nehru’s failed promise of a plebiscite, India’s de facto control of the Kashmir valley rests on the basis of a military ceasefire line dating from 1948.

Within just the Indian side of that line, the complexities are significant and one has to consider the rival claims of the Dogri-speaking Hindus of Jammu, Kashmiri Muslims of the valley, the Tibetan Buddhists of Ladakh, as well as the displaced Kashmiri Hindus living outside the state. A final resolution of this kind, much discussed and debated over the decades, and the subject of many books, has always been on the cards, but perpetually postponed for some future government to handle, pending greater political will and better relations with Pakistan.

Kashmir will not have more autonomy, but less so and be more closely monitored and controlled

The protracted indecision of no-war, no-peace kept Kashmir on the edge in its present phase since the end of the militancy in the mid-1990s, and a deformed political spectrum evolved into existence in its shadow. Separatists and integrationists, moderates and militants co-existed within relatively predictable parameters of this ecosystem, and people operated within both these spheres in their public and private lives. After seven decades of incorporation into India, everyday acts of resistance to the occupation had come to live alongside, and blend into the everyday necessity to collaborate with it.

All this would come into question very suddenly as of 5 August. Buoyed by electoral success in May, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his henchman, Home Minister Amit Shah finally decided to end years of indecision by imposing a solution of their making. Shah, who is possibly the most powerful and dangerous man in India today, announced in parliament – with no prior warning or consultation – that the state of Jammu and Kashmir would no longer exist. As of 31 October, it would be carved up into two parts, its special status would be cancelled, and the state would be downgraded into a union territory, with considerably less powers, and more centrally governed from New Delhi.

At a stroke, the decades-long debate over autonomy or negotiations, and the productive ambiguity of various future options was brought to an end. India has unilaterally imposed a final solution in which there would, in fact, be no negotiations with the Pakistanis or Kashmiris about anything. Kashmir will not have more autonomy, but less so and be more closely monitored and controlled.

Amit Shah’s bill, announced for the first time ever in parliament on 5 August, passed through the upper house the same day, the lower house the next day, and was signed into an Act by the president three days later, while most of Kashmir was under lockdown and its leaders in jail. Barring a judicial challenge, it will become the new reality on 31 October. The 12 million people of Jammu and Kashmir were informed of this fate after the fact, and learned of it through television news.

Everyone knows this is collective punishment and imprisonment, and that those doing it to them are Hindu nationalists who make no bones about the fact that they hate Muslims

Modi and Shah have timing on their side. Domestically, they are in command of the political landscape, and at the peak of their powers after a resounding election victory to a second term. The abrogation of Kashmir’s special status, enshrined in article 370 of the constitution has played well to the gallery and has been so popular in the rest of India that it has divided the opposition. The only possible threat they face is a legal challenge in the supreme court, but the chances of that are slim given its present composition.

Internationally, with Trump still in post for the next year, and Europe mired in Brexit, the calculation is that there will be no serious pressure brought to bear on India. Putin’s Russia has supported India. China has made a largely tokenistic protest. Pakistan, on the other hand, has responded in complete outrage, and Imran Khan is in many ways, being forced to respond to a massive tide of public pressure by talking tough and taking whatever measures he can against India. This too, is not necessarily a problem for Modi and Shah, for whom the idea of locking horns with Pakistan in a hostile status quo is the default comfort position.

Anticipating the fury that would erupt on the streets, Shah ordered all non-Kashmiris – tourists and workers – out of the state in early August, deployed thousands of fresh security forces to control the inevitable civilian outrage, and locked up between two to four thousand people in preventive detention.

What was really extraordinary though was that it was not just the usual suspects in the separatist and pro-Pakistan leadership of the Hurriyat Conference who were detained, but also the entire ‘moderate’ pro-India leadership, who have been New Delhi’s interlocutors and who have governed the state on its terms for decades. The former chief ministers of Jammu and Kashmir, Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti, have suffered the indignity of being taken into indefinite custody and held incommunicado themselves. At the time of writing, they remain confined in Srinagar’s Centaur Hotel without any internet or phone connections.

Kashmir is no stranger to long drawn-out general strikes. The last one, which stretched out for several months, was in 2016, after the security forces gunned down a young Kashmiri militant Burhan Wani. But in 2019, there are no separatist leaders to call a strike – they are all in jail. Neither is there any email or mobile phones to communicate and spread the word. Yet there is a general strike going on, which is widely observed voluntarily, day after day. There aren’t many demonstrations or much stone throwing yet, but there is absolutely no mistaking the suppressed fury on the streets, waiting to erupt in some form. Kashmir has been angry in the past, but this time, it is more widespread, more profound, and more reckless than before.

Everyone knows this is collective punishment and imprisonment, carried out by Hindu nationalists who make no bones about the fact that they hate Muslims and want to drive them out. With the moderates locked up and publicly disgraced by their erstwhile patrons, the options presented to Kashmiris are now are much simpler – they are the extremes of total capitulation or total defiance.

This is exactly what Shah Faesal, a young Kashmiri politician who was previously in India’s prestigious civil service corps tweeted: “You can either be a stooge or a separatist now. No shades of grey”. And it doesn’t take much to get people to say this in different ways, whenever the opportunity presents itself. Journalists, hotel receptionists, old friends, doctors, airline staff, off-duty poets, taxi drivers, and shopkeepers sitting outside their shuttered shops all said it with passion and conviction. Even Kashmiri policemen say it, but they whisper it, in the same tone of perplexed but desperate defiance. “Why are they doing this to us? … India is leaving us with no option ... What else do we have to lose now? … We will never give up or accept this …”

After a long hot day standing on the edge of Lal Chowk, the policeman also wanted to talk. He quickly became animated, holding his rifle in one hand and the riot shield in another. People didn’t understand what the CRPF had to go through. He was from Chattisgarh, some 1500km away, and he too was a victim of the communications blockade. He hadn’t been able to speak or text his family since he was deployed to Srinagar three weeks back, and his mother would be worried, glued to the news channels every hour for the latest on Kashmir. “They don’t have any idea what it’s like here, but in a way, that’s good,” he says. ”Go back to Delhi, sir. Things look okay here now, but this is just the beginning.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments