Le Roi du Crazy: Was Jerry Lewis a nincompoop or a comic genius?

With Lewis’s ‘The Nutty Professor’ set for an unlikely screening at this month’s Berlin Film Festival, Geoffrey Macnab looks back on the life and career of a comedian revered by the French but sneered at elsewhere

Alongside all its premieres of new work from the most revered European art-house directors and symposiums on the future of cinema, this month’s Berlin Film Festival is to hold a special screening of an unlikely film. The original Jerry Lewis version of The Nutty Professor (1963) will be shown in the Haus der Berliner Festspiele, one of the city’s most prestigious venues. The star’s son, Chris Lewis, is expected to be in town for the event that is being held to mark the donation of new documents from the comedian’s estate to the Deutsche Kinemathek.

Scoffers will react with the usual cynicism to seeing Lewis (1926-2017) celebrated in this way. To many, he is still the nincompoop who goofed around opposite the urbane and understandably exasperated Dean Martin in all those film comedies (Sailor Beware, The Caddy etc) that used to be shown on a permanent loop on British television in the school holidays. He was American cinema’s answer to Norman Wisdom.

Contemporary critics tended to be very sneering about Lewis. “Sticky and unfunny,” The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther wrote of The Stooge (1953), although Crowther had been more generous than many other reviewers when Lewis first appeared on-screen alongside Martin, in My Friend Irma (1949). “This freakishly built and acting young man … has a genuine comic quality. The swift eccentricity of his movements, the harrowing features of his face and the squeak of his vocal protestations, which are many and frequent, have flair,” Crowther wrote, calling him the “funniest thing” in a film otherwise hardly worth seeing. He noted the comedian’s “genuine talent for first-class satiric mimicry”.

However, the influential American writer Andrew Sarris railed against what he called the “simpering simple-mindedness” and banality of Lewis’s work. The Sarris line was widely shared among US critics.

As has been well chronicled, Lewis’s critical reputation was “rescued” by the French who decided he was a genius. For some, this was just another reason to mock him. The Cahiers du Cinema and Positif critics wrote about him in such absurdly exalted terms that they only succeeded in making him seem yet more ridiculous. The comedian was called “Le Roi du Crazy”, and “the complete master of a magical world that could be called Lewisland”. French academics likened him to Moliere and Beaumarchais. Any Anglo-Saxons looking to caricature French cineastes as pretentious and deluded would always reach for Lewis.

Three years after his death, Lewis’s reputation is undergoing yet another shift. American filmmakers and critics now regard him much as the French do. It was instructive to watch French filmmaker Gregory Monro’s hagiographic documentary about Lewis, The Man Behind The Clown (2016), which received its world premiere at the Telluride Film Festival. Alongside the predictable European enthusiasts, Martin Scorsese, who directed Lewis in The King of Comedy (1982), features prominently in the documentary.

“The French in a sense gave us American cinema, the post-war critics in France. They hadn’t seen any American films during the German occupation and then all those films flooded into the country at once. Their appreciation of those films allowed us to see our pictures in a different way,” Scorsese suggests in the film.

“The idea that the French revered [Lewis] became a joke of itself. Nowadays, the people who are keeping the joke alive know really nothing about Jerry Lewis and particularly his films,” Scorsese added.

Arguably, what all those uninformed detractors referred to by Scorsese don’t know about the comedian’s work is that his films are becoming so hard to find.

The irony is that, whether in Europe or the US, you are now far more likely to find Lewis’s films in a cinematheque or at a festival alongside those of his admirers like Jean-Luc Godard and Louis Malle than in a mainstream cinema or on TV. In becoming accepted as one of the great artists of American cinema, he has somehow lost his popular touch.

The Nutty Professor (1963), Lewis’s fourth film as a writer-director, supports those lofty claims that the comedian’s admirers make about his comic genius. It’s a brashly shot Technicolor reimagining of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde that combines superbly orchestrated stunts with sly satire. It also shows off Lewis’s versatility as an actor. He plays both the toothsome, supremely nerdy scientist, Professor Julius Kelp, and Buddy Love, the long lizard Loathrio he turns into when he takes the potion he has concocted in the labs.

The film is regarded as one of his masterpieces but US audiences and critics were clearly discomfited by it at the time of its release. It’s a subversive affair which, seen today, has as much in common with Fight Club as with the Robert Louis Stevenson classic on which it is ostensibly based.

To cinemagoers accustomed to Lewis as a loveable loser, it was startling to see him on screen as an alpha male like Buddy Love. Lewis plays Buddy with absolute assurance. He is slick, charismatic and casually violent. The first time we see him, he humiliates a barman, beats up an onlooker, slugs back a cocktail with a strong enough alcohol content to knock out a mule, faces down the college jocks, whisks beautiful young student Stella Purdy (Stella Stevens) on to the dance floor and then launches into an impromptu, crooning rendition of “That Old Black Magic” with the house jazz band.

One reason reviewers reacted so ambivalently to The Nutty Professor was that they saw it as Lewis getting his own back on Martin. The writer-director-star strongly, if disingenuously, denied that he was settling scores with his old partner. Buddy shares Martin’s dress sense, his mannerisms and his swagger. The difference, though, is the sheer destructive force of Buddy. You marvel not just at Lewis’s performance as Buddy but at the glee with which he skewers an all-American archetype. The film is subversive in its suggestion that men like Buddy, generally portrayed in Hollywood films of the time as heroes, are, in fact, delinquent psychopaths. They’re also deeply insecure. Some of the funniest moments in the film come when Buddy falters, his voice begins to croak, his teeth suddenly protrude and his inner nerd takes over.

The American critics were “lukewarm” but, true to form, the French adored The Nutty Professor. Lewis was invited to Paris to pick up a “director of the year” award. Denied the recognition he acknowledged he desperately wanted at home, he received it in spades in France. “A coronation of sort, and my crown was sweet revenge,” he wrote.

As a filmmaker, Lewis is a contradictory figure. His old friend and mentor Frank Tashlin, who directed Lewis many times on screen, claimed that Lewis hated rehearsal. “Jerry never rehearses. Just one take and that’s it. You rehearse with Jerry and you’ll die. He doesn’t look at his dialogue until he walks on the set, and he never sticks to the lines anyway – usually, he makes them better. I just tell him roughly what the scene is and he does it,” Tashlin explained about their working relationship. However, on the films he himself directed, Lewis was a perfectionist and a control freak. Godard used to marvel at his flair for composition and “symmetry”.

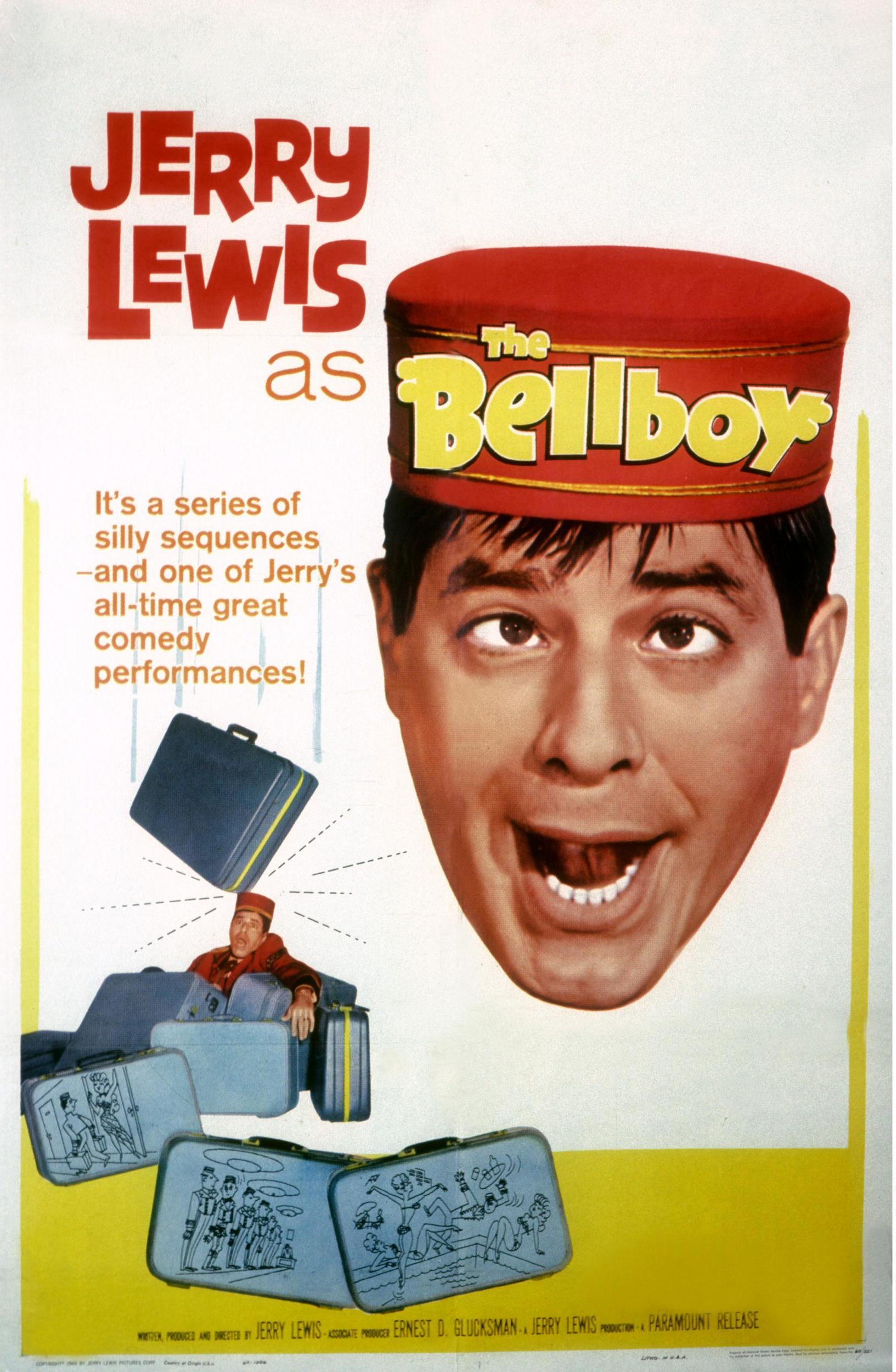

Lewis worked very quickly. In his autobiography, In Person, he claims that he began writing The Bellboy (1960), in January; started shooting the next month and “cut the picture, scored it, dubbed it and shipped it in May to Paramount for distribution”. This rapidity seems all the more startling when you realise he was also performing live throughout much of this period. The film doesn’t look as if it was thrown together in a rush. Lewis paid the same exhaustive attention to costume and production design as he did to getting the comic timing right. The Nutty Professor has bravura moments, like the sequence seen from Buddy’s point of view when he is seen walking into the nightclub, which bears comparison with the famous steadicam shot at the start of Scorsese’s Goodfellas.

The latter part of Lewis’s career is perplexing. He “wouldn’t play the game” and his directorial career trickled to a halt as a result. In the Easy Rider Hollywood, he began to seem old- fashioned. His Holocaust drama, The Day The Clown Cried, about a clown who accompanies children to their death at Auschwitz, was never released. He became as famous for his telethons, raising vast amounts of money for the Muscular Dystrophy Association, as for his movies. He was widely praised for his uncharacteristically serious performance in Scorsese’s The King of Comedy but had seemingly lost the desire to lay claim to that title for himself. He was as much in the public eye as ever but remained a polarising figure.

Now, after his death, Lewis is being taken more seriously than ever before as a filmmaker. His own films may have fallen out of circulation but his influence on later screen comedians from Jim Carrey, Mike Myers and Eddie Murphy (star of The Nutty Professor remake) is obvious. In Berlin in a few weeks, the Deutsche Kinemathek will take possession of many of his papers, including his own copy of the script of The Day The Clown Died as well as stills, correspondence and previously unseen behind the scenes footage. Given the subject matter, it is likely to be a sombre occasion… at least until the screening of The Nutty Professor begins, when the mood is bound to lift.

The Nutty Professor will screen at the Berlin Film Festival on 22 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments