Why bringing James Dean back from the dead through CGI is proof of the diminishing allure of today’s stars

More than six decades after his death, the ‘Rebel Without a Cause’ actor is making his big-screen return in Vietnam-era action drama ‘Finding Jack’. As Hollywood trashes his memory, it’s obvious no star is sacred, says Geoffrey Macnab

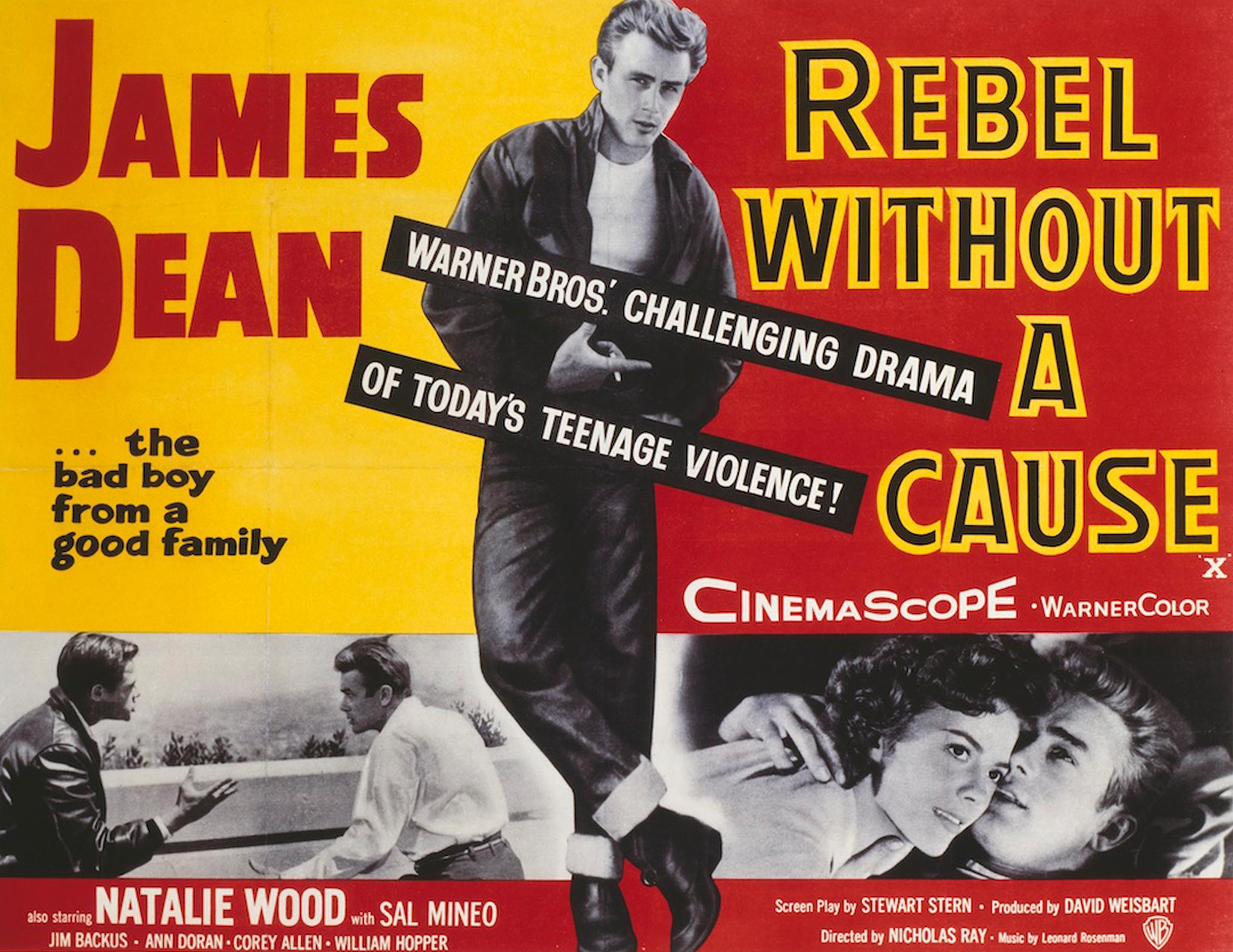

It was hard to avoid a sense of absolute dismay last week when little known filmmakers Anton Ernst and Tati Golykh announced through trade paper The Hollywood Reporter they had cast James Dean in their new film. The Rebel Without a Cause star, who died in a car crash in 1955, is to be resuscitated through CGI by visual effects companies in Canada and South Africa to play one of the roles in their Vietnam war drama, Finding Jack. Dean’s family granted the filmmakers the right to use his image.

“We never intended for this to be a marketing gimmick,” Ernst commented after the news of Dean’s digital rebirth was greeted with fury by many observers. Showing extraordinary naivety, the director expressed surprise that so many people were so upset. It somehow eluded Ernst that Dean’s short career (which ran to only three movies) had been based around an absolute refusal to compromise or cheapen his image to keep the studio bosses (“those bastards at Warners”) happy.

“To work with Jimmy meant exploring his nature; without that his powers of expression were frozen,” said Nicholas Ray, who directed him in Rebel Without a Cause. Ray pointed to the actor’s “urgent, probing curiosity … every day he threw himself upon the world like a starved animal after a scrap of food”.

Elia Kazan, Dean’s director in East of Eden, talked of the unique power of cinema to capture feelings, saying: “In film, you can photograph a person thinking, you can photograph thought. The camera can also be used as a microscope; it is a penetrating device by which you can photograph the inner experience of a person, particularly a sensitive person.”

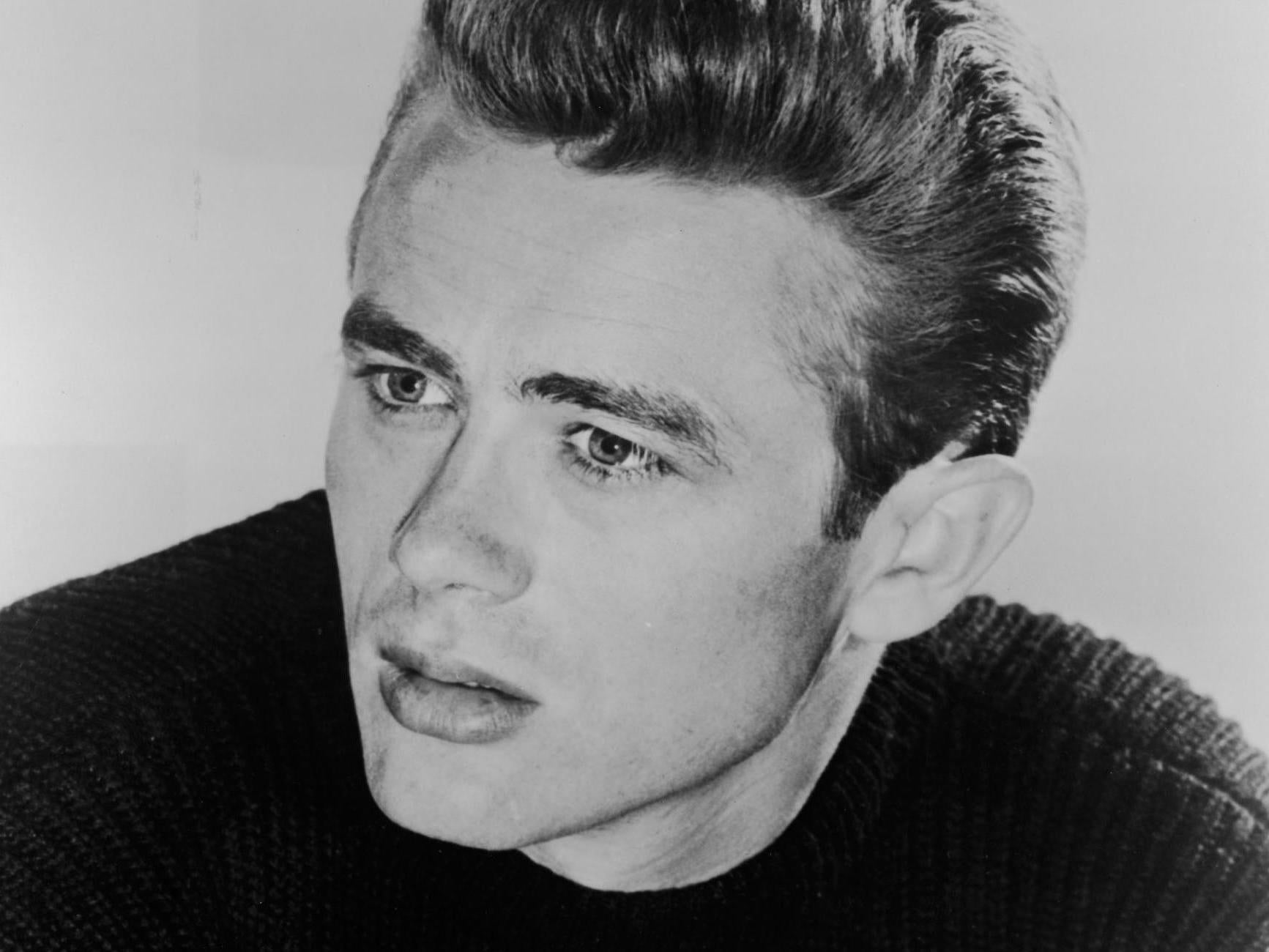

Dean, of course, was hyper-sensitive, morose, moody and charming but aloof.

“I’m a serious-minded, intense little devil, terribly gauche and so tense I don’t see how people stay in the same room as me,” he told LA Times. There is very little chance we will see any of that intensity or devilry in Finding Jack (if the film is ever made). Obviously, the new digital version of Dean, who will be voiced by another actor, is going to be one-dimensional: a computer-generated simulacrum of Dean rather than the real thing. The filmmakers may be able to recreate his appearance (the pompadour haircut, the moody scowl, the jeans, the leather jacket or, in this case, army fatigues) but they won’t be able to tap into what made him so special, namely his sensitivity and mixture of wildness and vulnerability.

The most depressing aspect of the ill-conceived attempt to bring Dean back from the dead is the contempt it reveals. The actor is being treated as a brand rather than a human being. “This opens up a whole new opportunity for many of our clients who are no longer with us,” Mark Roesler, CEO of CMG Worldwide, was quoted as saying in the Hollywood Reporter story on Dean. Roesler raised the possibility that if the Dean experiment worked, his company could press-gang, zombie-style, plenty of other deceased personalities whom it represents – Burt Reynolds, Christopher Reeve, Ingrid Bergman, Bette Davis and Jack Lemmon among them.

Stars used to be the single most important factor in getting films financed and in attracting audiences to them but now their status is much reduced. They seem to be worth as much dead as alive. However, one reason why filmmakers are so keen to exhume older stars is that so few of today’s actors have the same recognition factor.

Earlier this month at the American Film Market (AFM), an annual event in California’s Santa Monica where independent distributors from all over the world come to acquire new movies, it was noticeable how few star-driven “packages” were available. In years past, producers would announce dozens of new projects with big names attached. The distributors would happily buy these projects in advance on the basis of the actors involved, thereby enabling the films to be made. Now, the occasional Gerard Butler or Liam Neeson action thriller apart, very few independent films achieve meaningful “pre-sales”. The buyers prefer to wait to see the finished films. The stars are just another element to be considered rather than the defining element that guides distributors’ choices. The distributors are just as likely to be guided by storyline or genre (horror and family dramas seem especially popular) as they are by stars such as Johnny Depp or Angelina Jolie.

One of the bigger titles presented at the AFM was A Special Relationship, a new biopic of Elizabeth Taylor from See-Saw Films (the company behind The King’s Speech) starring Rachel Weisz. The film will explore Taylor’s journey from “actress to activist”. Weisz is a highly accomplished actor, with a very broad range, but Liz Taylor she isn’t. Her name is not enough on its own to sell the movie. She doesn’t wear the jewellery or have the tantrums or fascinate the paparazzi in the way that Taylor once did.

Lead actors in the Marvel superhero films (for example Robert Downey Jr or Scarlett Johansson) may earn millions but no one talks about going to see a Robert Downey Jr movie, a Chadwick Boseman film or a Gal Gadot film. The franchise is far bigger than the individuals in the films.

The same CGI chicanery proposed to bring James Dean back to life has already been used to keep the late Carrie Fisher in the new Star Wars film. (It helps that there is also unused footage of Fisher that can be spliced into the movie.) Whether this constitutes a “real” performance from Fisher is another question.

Devoted fans may turn up in huge numbers at Comic Cons, ready to pay for the autographs of their favourite actors. But their enthusiasm is driven by the blockbusters these stars appear in, rather than by the stars’ work as a whole. They’ll fuss over Daisy Ridley when there is a new Star Wars on the horizon, but there is no sign that they’re rushing to buy tickets for her new indie drama Ophelia (the Hamlet story told from Ophelia’s point of view) which is released later this month in the UK on only a handful of screens.

Paradoxically, although the star system is now under threat as never before, these are boom times for screen actors. Thanks to the immense amount of new drama commissioned by the streaming giants, the range of roles available has grown significantly. Top actors can earn fortunes in long-running TV and online series or blockbuster movies and then take parts between them in independent films, for which they will be paid far less – but which they see as a rewarding challenge. However, even the most expensive TV dramas don’t offer the red carpet opportunities and saturation media exposure afforded by a big movie premiere.

One trend evident in the market is the emergence of an “old wave” of movie stars. Judi Dench, Maggie Smith, Celia Imrie, Vanessa Redgrave and others are still considered bankable even as younger stars struggle to make an impression at the box office. This may reflect the changes tastes of younger cinemagoers, who don’t seem as interested in stars as their parents.

The audience is also becoming far more fractured. Actors can have ardent fans among the viewers of their TV dramas, without coming close to the blanket fame enjoyed by stars in classical Hollywood films, almost as a matter of course. If James Dean was to emerge today, you simply can’t imagine him reaching anything like the level of celebrity he achieved even before his final film, Giant (1956) was released after he was killed. In today’s distribution climate, East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause would be regarded as Sundance-type films, worth a limited release at best.

“His behaviour and personality seemed to be part of a pattern which invariably had to lead to something destructive. I always had a strange feeling that there was in Jimmy a sort of doomed quality,” Dean’s acting coach Lee Strasberg said of him. Inevitably, Dean’s untimely death added to his mystique. The plan to bring him back from the grave through CGI can’t help but seem like an act of wanton vandalism, a way of tarnishing a Hollywood icon that risks making him seem mediocre. He appeared in three films with directors (Kazan, Nicholas Ray and George Stevens) who were all titans of the industry. Now, as Hollywood trashes his memory, it is obvious no star is sacred.

“Live fast, die young and leave a good-looking corpse” is a phrase often attributed to Dean (although it was first coined by novelist Willard Motley). The quote won’t have quite the same resonance if Dean’s image is going to be recycled in such a crass and opportunistic way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments