Revealed: The plot to spy on Jamal Khashoggi’s wife

Hanan El-Atr lost her husband just four months after they were married. That loss is all the more bitter because spyware on her phone allowed her husband’s enemies to track his movements, reports Andrew Buncombe

Hanan El-Atr, the widow of Jamal Khashoggi, always felt she was being spied on. Now, she has proof. In April 2018, six months before the journalist was murdered inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul by a hit squad dispatched by Riyadh, she was pulled over by the Emirati authorities at Dubai International Airport, and questioned.

She had deleted from her British phone, three WhatsApp messages she had sent to a Moroccan singer living in London and a journalist in Qatar. Yet, her interrogators knew the content of those messages. “Telling me the content of the messages at the beginning of my detention really scared and I couldn’t recall a thing to answer their questions,” says El-Atr, who for a number of years worked as a flight steward for Emirates Airlines.

“I have nothing to hide, but they keep threatening me, saying they will get my family, or torture my family in front of me to answer their questions. Or they will hand my family over to Egyptian intelligence to be tortured or sent to jail or even killed.”

El-Atr and her lawyer, Randa Fahmy, say they have proof both her phones were targeted by an NSO Group spyware programme known as Pegasus. NSO Group has denied its spyware was involved in the murder of the commentator and broadcaster, or that his family members were monitored.

Last year, analysis carried out on behalf of Amnesty International revealed El-Atr, along with Hatice Cengiz, the Turkish woman said to have been engaged to the journalist, were among dozens of figures around the world – among them, politicians, dissidents and journalists – to have had their phones targeted by the spyware. El-Atr’s British phone had been targeted via spyware contained in SMS messages that were sent to her.

One said: “You got a flower bouquet”. Another read: “Look at these pictures.”

But recently, experts from the Toronto-based Citizen Lab, along with another specialist hired by Fahmy, uncovered what they said was proof that El-Atr’s second phone, which had an Emirati number, had been compromised. Perhaps most astonishingly, they found the software had been manually downloaded from the internet while both phones were in the custody of the Emirati authorities, and she was being questioned by their agents. The developments were first reported by the Washington Post.

Bill Marczak, a senior research fellow at Citizen Lab, termed it the “smoking gun”.

El-Atr and Fahmy are now preparing for legal action against the NSO Group, accusing it of being party to the journalist’s death. And they are using the analysis and the proof it has given them to step up their efforts to press for justice for her husband, three-and-a-half-years after he was murdered. “It’s fairly clear to me that there are three parties who were responsible for Jamal’s death, and they will be held accountable,” says Fahmy.

Two of those are countries – Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. “The other is the NSO Group. They’re being sued right now by WhatsApp and they’re being sued by Apple,” she says. “They’re also being sued by a number of parties.” She adds: “We are presently assembling our legal teams.”

Yet, the proof her phone had been compromised has created fresh grief and even a sense of guilt for El-Atr. The Pegasus spyware not only tracks a person’s movements or copies their text messages, it can also turn on a phone camera and microphone. Often, her phone would on the table when she and Khashoggi spoke together at his apartment in the suburbs of Washington DC. Unknowingly, she says, she helped her husband’s enemies set a “trap” for him.

Confirmation that the widow of Khashoggi was targeted using the software, comes as the NSO Group has been under fresh and intense global scrutiny. A recent investigation by the New York Times revealed how the software had been sold to numerous nations, including countries such as Hungary, India and Poland, which have human rights records that are less than stellar. In India questions have been asked of the country’s nationalist prime minister, Narendra Modi, in the nation’s parliament.

In the US, which has made use of the software to help track individuals such as Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the notorious drug lord known as El Chapo, there has been a rethink at the highest levels of government. In December 2021, the Biden administration blacklisted the NSO Group, saying its technology had been knowingly provided to foreign governments to “maliciously target” the phones of human rights activists, lawyers and journalists.

The US is committed to aggressively using export controls to hold companies accountable that develop, traffic, or use technologies to conduct malicious activities that threaten the cybersecurity of members of civil society, dissidents, government officials and organisations here and abroad

In a statement that appeared to stun the Israeli technology firm, US Commerce Secretary, Gina Raimondo, said: “The United States is committed to aggressively using export controls to hold companies accountable that develop, traffic, or use technologies to conduct malicious activities that threaten the cybersecurity of members of civil society, dissidents, government officials and organisations here and abroad.”

In January 2022, the US went further, when the National Counterintelligence and Security Centre, part of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, issued advice on how individuals could protect themselves against being spied upon. “Companies and individuals have been selling commercial surveillance tools to governments and other entities that have used them for malicious purposes,” the authorities warned.

“Journalists, dissidents, and other persons around the world have been targeted and tracked using these tools, which allow malign actors to infect mobile and internet-connected devices with malware over WiFi and cellular data connections. In some cases, malign actors can infect a targeted device with no action from the device owner.”

A spokesman for the NSO Group repeated in a statement: “As NSO has previously stated, our technology was not associated in any way with the heinous murder of Jamal Khashoggi or any of his family members, including Hanan El-Atr. Publishing these false statements is defamatory and won’t change the reality.”

Marczak says their work has for the first time uncovered a case where the Pegasus software was added manually to someone’s phone. “It was the first time we had established this really good quality evidence that at some point the spyware had been on the phone,” he says.

“Previously, on Android phones, we’ve seen initial targeting via the voice SMS or something like that WhatsApp message, but we’ve never seen any subsequent activity of the spyware on the phone. So this was the first one where we were able to make that additional leap on Android, which is, you know, much tougher to do forensics on than the iPhone.”

Marczak says Android phones are harder to hack simply because they carry less data than an iPhone. But he says the analysis of this and others proves that at some point, someone opened the web browser on Elatr’s phone and downloaded the software. He says the timing of the infection came when she was in the custody of the Emirati Authorities, as she was placed under house arrest after the initial interrogation.

But why would the Emiratis need to manually infect the phone if the software can be added by an SMS or WhatsApp message?

“Usually the remote infection is through one of these links that are sent to the target and the target has to be socially engineered to click on the link. This takes the person out of the loop,” he says. He adds: “From time to time, they do have these so-called “zero click” exploits to work without the target taking any action. But those are highly dependent on the exact type of device, the exact version of software running on the device. They are not available all the time, just because they’re very technically complex to develop and maintain.

“Hannan did not need to click on the phone or do anything. They just take the phone, infect it and give it back to her.”

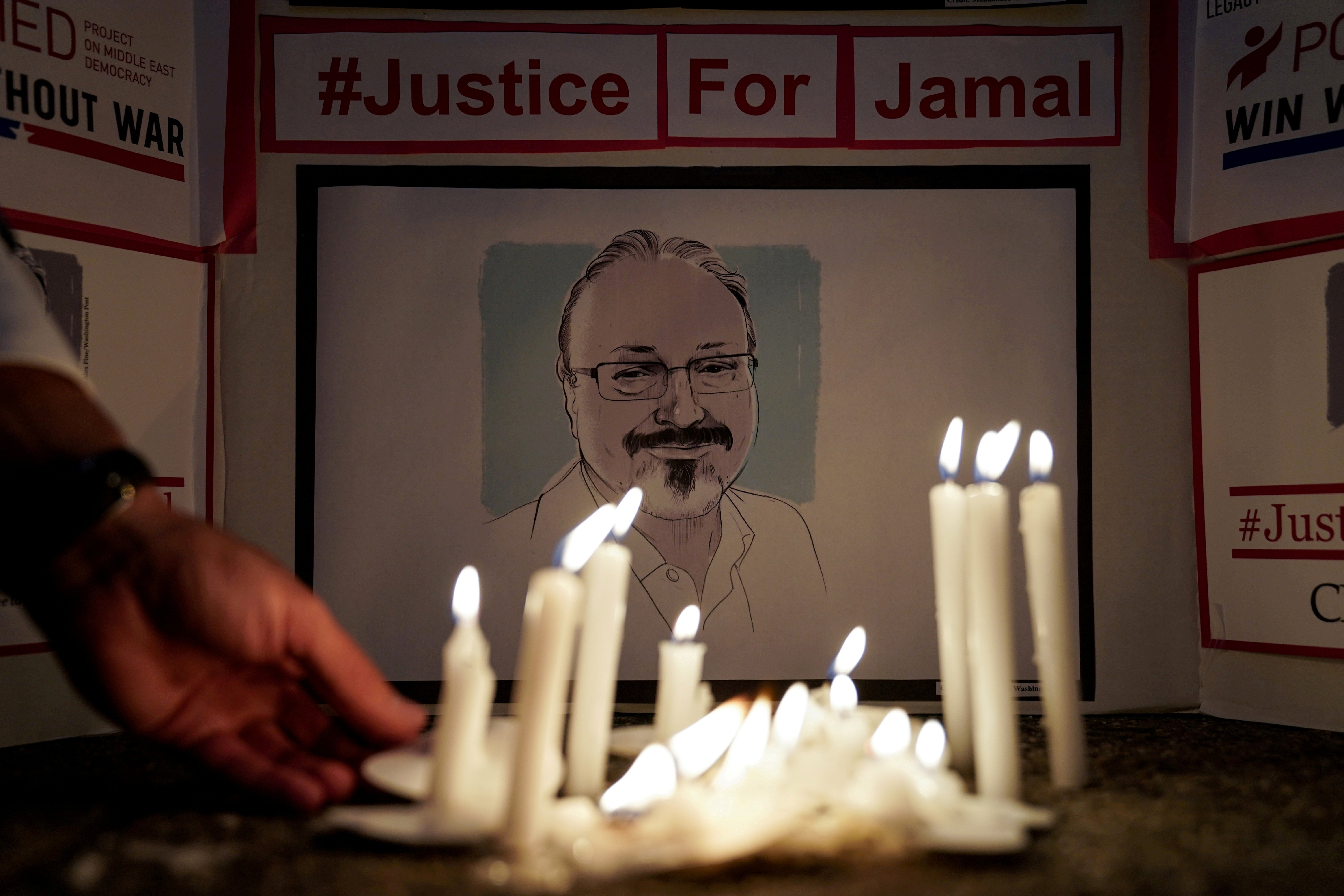

Jamal Khashoggi, 57, a celebrated journalist and most recently a columnist for the Washington Post, was murdered in October 2018 after entering the Saudi consulate, apparently in order to obtain a visa. It emerged he had been planning to visit Saudi Arabia and he had gone to the consulate that day with Hatice Cengiz, a Turkish student to whom he had apparently proposed marriage. Cengiz, now aged 40, had waited outside for Khashoggi, but he never came back.

In the days and weeks that followed it would emerge that Khashoggi had been murdered by a 12-strong hit team, and his body dismembered by a bone saw. It was alleged he had been murdered on the orders of the highest level of the Saudi state, after falling out with the authorities. Saudi Arabia denies the accusations and claimed he had been killed by “rogue” officials.

A report published in 2019 by Agnes Callamard, the UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions, said Saudi Arabia was responsible for “premeditated execution”. In addition, she said that there was credible evidence of the liability of crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, known as MBS.

In February 2021, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence said MBS had approved the operation to capture and kill Khashoggi. In the time since the killing, much attention has focussed on Hetice, who has sued the Saudi authorities and demanded justice. But the murdered journalist’s personal life was much more complicated: El-Atr says she first met Khashoggi in 2009 and that their relationship became more serious in 2017, when the journalist left Saudi Arabia for the US, determined to make a new life.

She says she visited him in the suburbs of Washington DC in the spring of 2018 at his invitation. In June of that year, they were married by Anwar Hajjaj, an imam in northern Virginia. It took her and her lawyer more than a year, and the threat of legal action, to obtain the document proving they were married. The two women did not know of each other.

The revelations have also put into sharper focus the role of Saudi Arabia as a major power player in the Middle East, and its increasingly close ties with the United Arab Emirates, a federation of seven monarchies. The most powerful of these is the emirate of Abu Dhabi, the leader of which is crown prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (MBZ).

Many consider MBZ to be the de facto ruler of the UAE. He and Saudi Arabia’s MBS are known to be close. Since 2011, and the weakening of regional powers such as Egypt, Iraq and Syria, the two countries have been increasingly forward leaning. In 2012, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, members of what is termed the Gulf Cooperation Council, signed a security and intelligence agreement.

Human Rights Watch was among various groups to warn those countries could use the agreement “to suppress free expression and undermine privacy rights of citizens and residents”.

Most recently, in December 2021, MBS visited the UAE during part of a mini-tour of Arab states. “The excellent relations between our countries keeps growing stronger as they are founded on fraternity, history, geography and common interests,” MBZ said in a statement. “Saudi Arabia has been, and will always be a key regional player. We are confident that together, we will be able to confront all challenges in the region and to maintain our common interests and the welfare of our peoples.”

Neither the foreign ministry of the UAE or its embassy in Washington DC responded to inquiries from The Independent. The foreign ministry of Saudi Arabia and its embassy did not respond.

A spokesperson for the NSO Group said: “As NSO has previously stated, our technology was not associated in any way with the heinous murder of Jamal Khashoggi or any of his family members, including Hanan El-Atr. Publishing these false statements is defamatory and won’t change the reality.”

Khashoggi’s widow says she now must secure justice for her late husband, and pursue anyone involved in his murder. “I feel there’s more responsibility on me. With [my lawyer’s help] I’m going after all parties, individuals or countries, to be charged, and to be accountable for the death of my husband,” she says.

“I could not lead a media campaign before or make a noise because I did not have a solid evidence.”

With the evidence provided by the analysis of her phone she says she is determined to push ahead. She suspects the Saudi or Emirati authorities had in all likelihood been monitoring her and her social media accounts since 2016 when she posted something in support of Khashoggi.

El-Atr, who calls herself Hanan El-Atr Khashoggi, and her lawyer are also appealing to the Turkish authorities to return to them Khashoggi’s cell phone and other belongings, seized as part of the investigation. They have written to the Turkish ambassador, Hasan Murat Mercan. The embassy has not responded to inquiries.

“We will get more evidence as to which country was watching my husband,” she says. “If they are watching me and my British number it means they were also following my husband and they made a trap to get him to Istanbul.”

She also wants to continue her husband’s efforts to highlight the cases of political prisoners in Saudi. El-Atr says that when she learned her lawyer had obtained proof her phone had been compromised, she felt “very bad, and devastated”.

Now, she says, the whole world knows who she is. Yet at the same time, she feels traumatised and lost. Other than her lawyer, she is confronting these powerful nations and companies by herself. “I’m still going through [the trauma] because I’m standing alone,” she says. “But now, I have the whole evidence in my hand.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments