Heaven, hell and Irish politics: Conversations with Gerry Adams and Ian Paisley

February 1997: Robert Fisk met Gerry Adams and Ian Paisley and spoke of war and peace and Ireland

There was a gin and tonic on the bar table and the former Northern Ireland Office official, features as gnarled as his cynicism, a Protestant as brutally honest about his own people as he is about Catholics, was waiting for me in his usual Belfast haunt. A quarter century ago, he would curse my pessimism. Now he was worse than me; and I was shocked. “Bob, I’ve never seen such sectarian hatred. You know, I was talking to a senior policeman the other day about Drumcree. He had been working for Chief Constable Annesley – whom we called ‘the eternal flame’ because he never went out – and I told this policeman that it all ended last summer at Drumcree when the RUC let the Protestants march through the Catholic streets. I said to him there was no way forward since the loyalists set aside the rule of law at Drumcree. It proved for everyone that the Protestants, when they take to the streets, have more power than the law.”

Drumcree has become a milepost of Northern Ireland history, like Bloody Sunday in Derry or the Protestant Ulster Workers’ Council strike that brought down the power-sharing Belfast government in 1974. In 1972, Bloody Sunday destroyed finally and for ever the British army’s credibility among Catholics. The Protestant strike destroyed the British government’s credibility among Catholics. And Drumcree, in the early summer of last year, destroyed the last shreds of Catholic hope that the RUC could be trusted.

Sometimes I suspect that Ulstermen take pride in these epic disasters. I must have been told 100 times – with pride, of course – that it was the men of east Belfast who built the Titanic. And like that state-of-the-art White Star liner, my old friend with the gin and tonic could see his province sinking ever deeper into its grave.

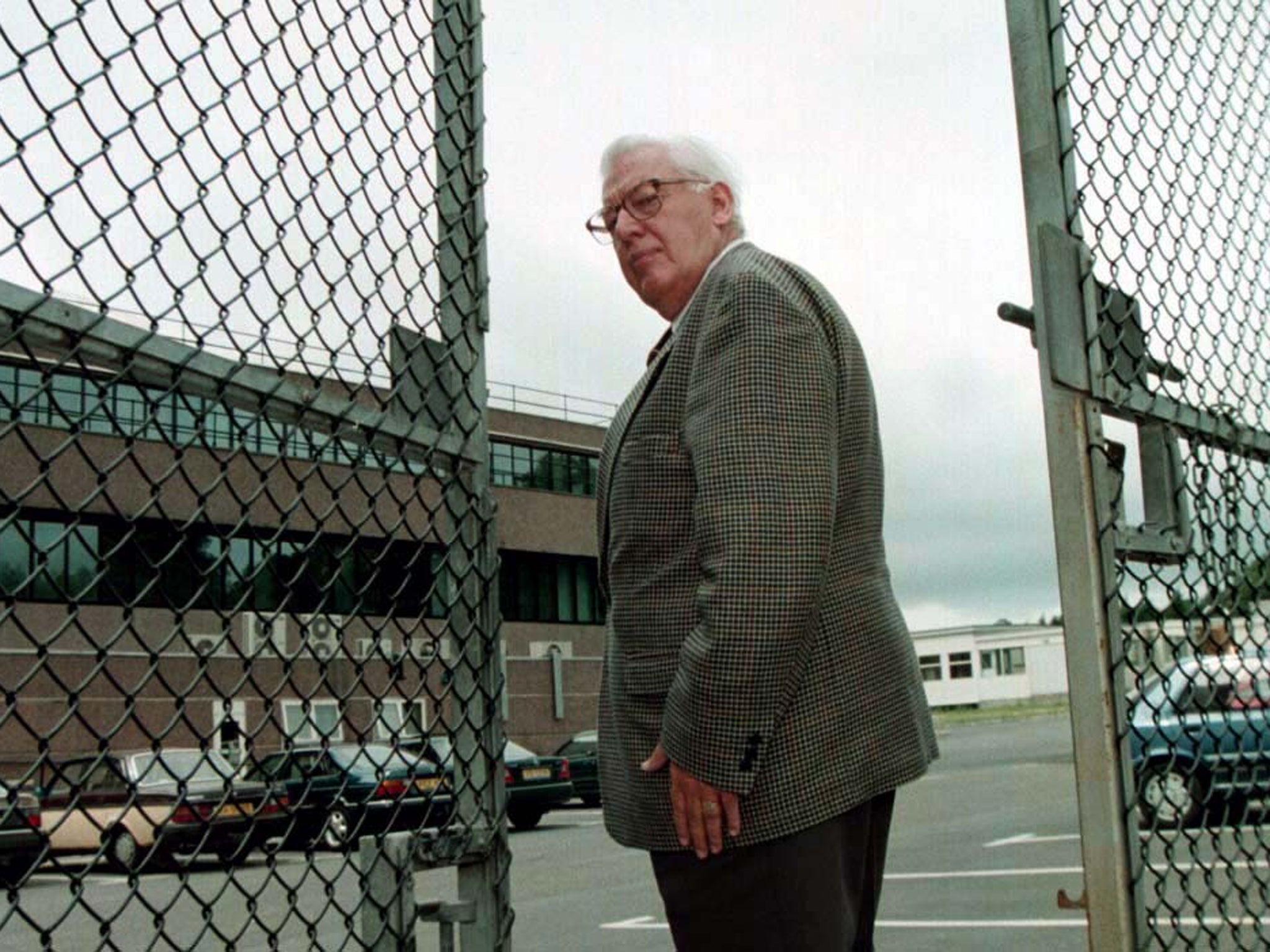

There was a terrible irony in all this. This same man – a trusted confidant of British officials – would abuse me for suggesting that Protestants could not live alongside Catholics, for ignoring “Protestant suffering at the hands of the IRA”. Yet just a few hours earlier, I had been walking up the Falls Road in the rain, listening to the political representative of that very same IRA as he insisted that peace could be obtained, that the British could bring it about – if only they would face up to Unionism. It was a droll conversation I had with Gerry Adams at the corner of Finaghy Road North as his bodyguard, pale green shades wrapped around his face, scanned each passing car with the moonbeam eye of a man looking for a gun barrel.

Watching Adams, I kept thinking about war. And he kept talking about peace.

“We took the British by surprise when we declared our ceasefire. They had a problem. They were saying that the war was being contained. And all of a sudden we were suing for peace – and it was out of their control. And so they wanted to slow it down, to forget the consensus that our peace was creating. And that’s why, after we had a ceasefire, there was an attempt to create new conditions.” I knew we would reach that fatal phrase, the “decommissioning of weapons”. I remember when I learnt of it over the BBC in Beirut – where the civil war militias were allowed to bury their guns on the promise that the future peace would make them irrelevant, turn them into museum pieces, like the civil war swords on the walls of English pubs.

He’d sit with anyone. He’d sit down with the devil. In fact, Adams does sit down with the devil

“When I first heard of ‘decommissioning’, I asked Martin McGuinness what it meant,” Adams said. (McGuinness was a gentleman who had a different role when I last met him 25 years ago in Derry, one rather closely associated with Armalite rifles.) “Well, McGuinness went through the dictionaries and couldn’t find the word. Then at last he said it means ‘taking out of commission’. And still I don’t know what that means. It’s an issue – I talked to Mayhew about it. But he never had any expectation he’d get his way. The point is that for a peace to work, it has to ‘click’. It hasn’t yet ‘clicked’ with the British.”

Now I could think of quite a lot of clicking – of a rather different kind – that had come from the IRA over the past quarter-century. And I wasn’t very impressed with the political mea culpas that came from Gerry Adams. “One of the things we’ve failed to do,” he said brightly, “is engage with British public opinion.” But you did, I said, at Canary Wharf last year. And Adams’s head turned suddenly towards me. He didn’t like the “you”. And he wanted to see if I was joking. I wasn’t. “I’m talking about political engagement,” he said and on we walked, a little faster than before, as if the rain were getting heavier. It wasn’t.

How easy it is for those Americans who have supported the military “efficiency” of the IRA to forget, as John Hume has acidly observed, that while 87 per cent of civilian fatalities in the past 25 years have been killed by nationalist or “loyalist” paramilitaries, more than one in two of all dead IRA men were killed by their own hand. What kind of an outfit is this that the British are so afraid of, I kept asking myself?

But then again, we sometimes ask why the militarily powerful Israelis are so apprehensive of a few thousand Hezbollah men in southern Lebanon. Is this because Israel needs an excuse to stay in southern Lebanon? Does Britain need an excuse to delay the peace process?

There are more parallels. We journalists experience a little hesitation in pointing out the flaws in a “peace process”. Suggest that the Middle East peace is unjust to the Arab nations, and we are condemned for being “against peace” – and thus sympathetic to “terrorism”. Suggest that the IRA, for all its viciousness, may have a point about arms “decommissioning”, and the same lies are told about us. Peace, it seems, can be a very dangerous commodity.

The parallels go even further. Just as Israel dictates American policy in the Middle East, so the Unionists believe – not without reason – that they can dictate British policy in Northern Ireland. In both cases, this makes the relationship between protector and protege unhealthy, even explosive, for their enemies. Which is why Adams wants the British to “face up” to Unionism and for Unionists to bargain with nationalists for an “accommodation”. He would sit down with Paisley. “The Unionists have real difficulty in ceasing to be top dogs – nationalists have had enough of that.”

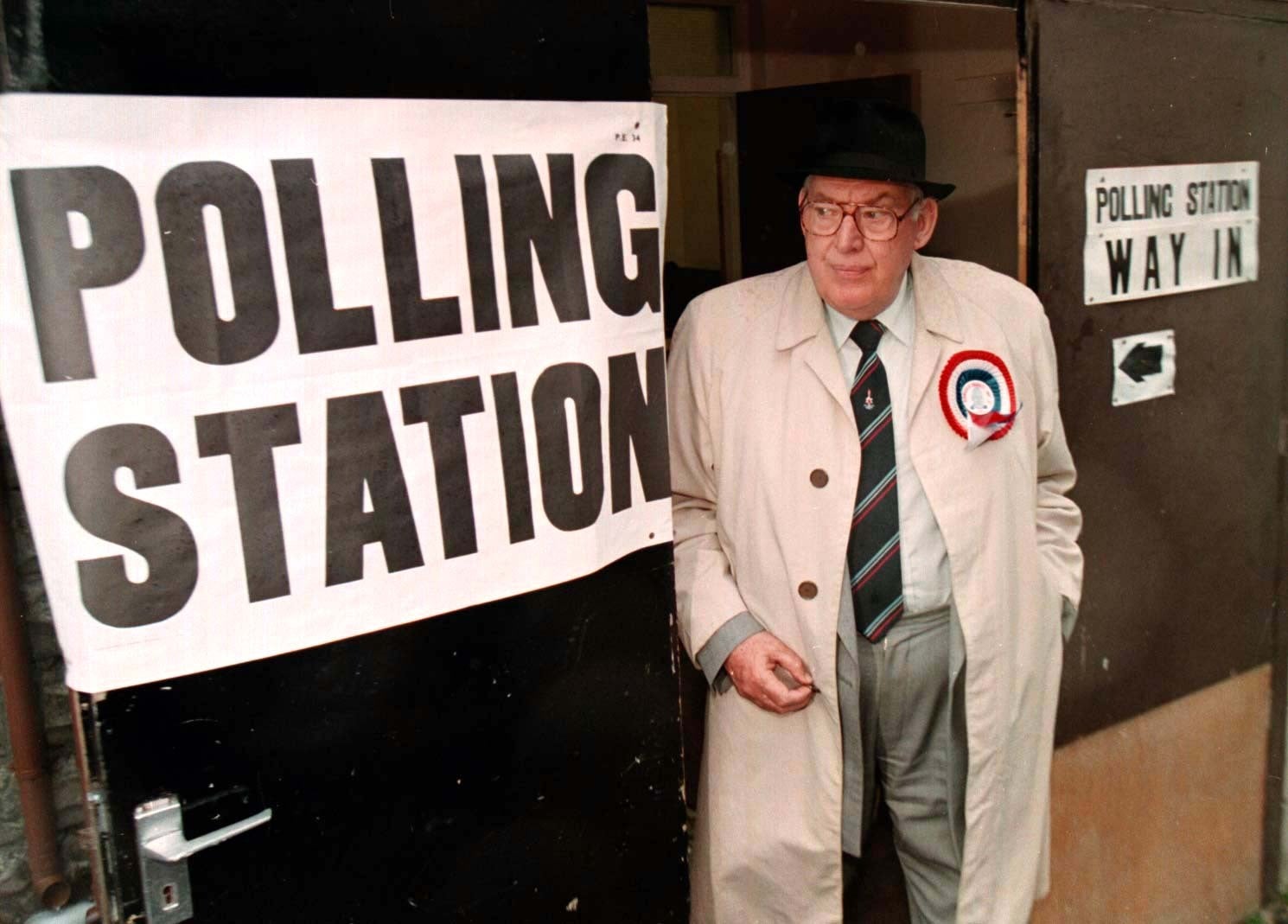

Is Dr Ian Paisley a “top dog”? He likes to be tame and wag his tail in a chummy way, watching you all the time to see if you spot the moment when he bares his teeth before clamping them firmly into your shin. Paisley saw no obvious parallels with the Middle East but surprised me with one of his first comments.

The Irish economy will dry up when European subsidies are drained, while the Irish themselves are disillusioned with their religion

“I’ve visited the Holy Land many times and I don’t doubt that the promised land was for the Jews,” he said. “But the Palestinians are a large body of people – and it was their land as well. I can well see their situation.” Somehow, I did not think he saw the Catholics’ situation in quite the same way.

We met in a stuffy Portakabin, crammed with plastic chairs, behind the Stormont offices where the hopeless “peace talks” are taking place. Paisley needs a church for his oratory but he was in fine form. The solution to Northern Ireland was “democracy” – ie majority, ie Unionist rule – and there was no fear of Catholics outnumbering Protestants, as recent statistics suggested. “I was taught as a youngster that in 50 years they would outnumber us. I’ve lived those 50 years and the figures are not much different. If the figures were that encouraging for them, the Republicans would have been content to let matters take their course.” The Irish economy will dry up when European subsidies are drained, while the Irish themselves are disillusioned with their religion: “They always thought we were lying about their priests.”

Drumcree was the fault of the nationalists – “the IRA had infiltrated the Garvaghy Road area” – and Catholics who remember Bloody Sunday should recall that two Protestant civilians were later killed by the same Parachute Regiment, which was why Dr Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party had refused to attend the Darlington talks that led to the power-sharing executive. The worst moment of the last 25 years was not Bloody Sunday but the IRA slaughter of 20 civilians at Enniskillen.

But at one point, Dr Paisley said something that could have been uttered by that most famous of all nationalist politicians, John Hume. Hume had told me 24 hours earlier that “in many ways what we need is a Unionist de Klerk – there are parallels between the South African situation and our own”. And now Dr Paisley said to me: “I would settle for what happened in South Africa – they got it by the maintenance of the Union of South Africa, and by majority vote.” But fear not, reader, the teeth were still intact in the old dog.

“I will never sit down with Gerry Adams.” But he’s just told me he’d sit down with you, I said to Paisley. “He’d sit with anyone. He’d sit down with the devil. In fact, Adams does sit down with the devil.” And if there is a devil, there must, of course, be a God. “I believe,” said Paisley, his voice rising, “that I will see God, as the scriptures make it clear, because I’m a sinner saved by grace. Every man stands on the common ground of sinnership. Yes, I believe heaven is a definite place, that God is a real person as revealed in the mystery of the Trinity.” This was heavy stuff. Our little Portakabin was turning into a Presbyterian chapel and I didn’t know how to halt the transformation. Yes, Paisley said, Protestantism was growing in the Republic. Why, a well-known IRA man south of the border had converted to Protestantism and was now among his church wardens.

This was too much. I tried to change the subject. Muslims believe in a rather colourful, physically attractive heaven, I said. Why didn’t Protestantism describe heaven? And the teeth flashed, quite literally, at me. “Ah Robert, you do not know your scriptures,” he boomed. And as Paisley delved into his pocket and produced a small red notebook with gold-edged pages, I felt the teeth closing. “Revelations, Chapter 22, verse one, ‘And he showed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb . . . and I saw an angel standing in the sun.’” Paisley’s voice was so loud in the tiny room that my ears began to hurt. “Revelations Chapter 21, verses one and two, ‘And I saw a new heaven and a new earth . . . And I . . . saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.’”

And I was thinking about Jerusalem when the voice suddenly stopped and lowered to prayer decibel. “Ah Robert,” it said, “you are an ignorant man.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments