What is a map for? In the modern era, technology has given us maps at our fingertips; satellites beaming live information to our phones so we can know in a moment the best (or, to be more accurate, quickest) way from A to B, wherever in the world those locations may be.

While the scale of the data available to us has expanded exponentially, for the most part we have reduced maps to route planners. No longer need we thumb through a printed road atlas, jotting down directions ahead of a long journey and noting alternatives in case of bad traffic. All that’s required now is to follow the highlighted line on the satnav, turning left or right as instructed. It is broadly unnecessary to know where you actually are until you reach your pre-programmed destination.

But maps can offer so much more than this. At the most basic level, they can show us what is just out of sight – the lay of the land beyond our immediate vision. Depending on their scale, they can show where we fit in the world’s family of nations, or the extent of a city’s built environment, or the contours of a neighbouring valley.

Above all, maps offer us context. They can help to explain why two states are embroiled in a dispute over territory, or how a conurbation has developed over hundreds of years, or why the ridge above the valley was such an important communications route in the distant past.

Maps can, if we let them, provide us with roots, as well as routes. But only if we both look, and act on what we see.

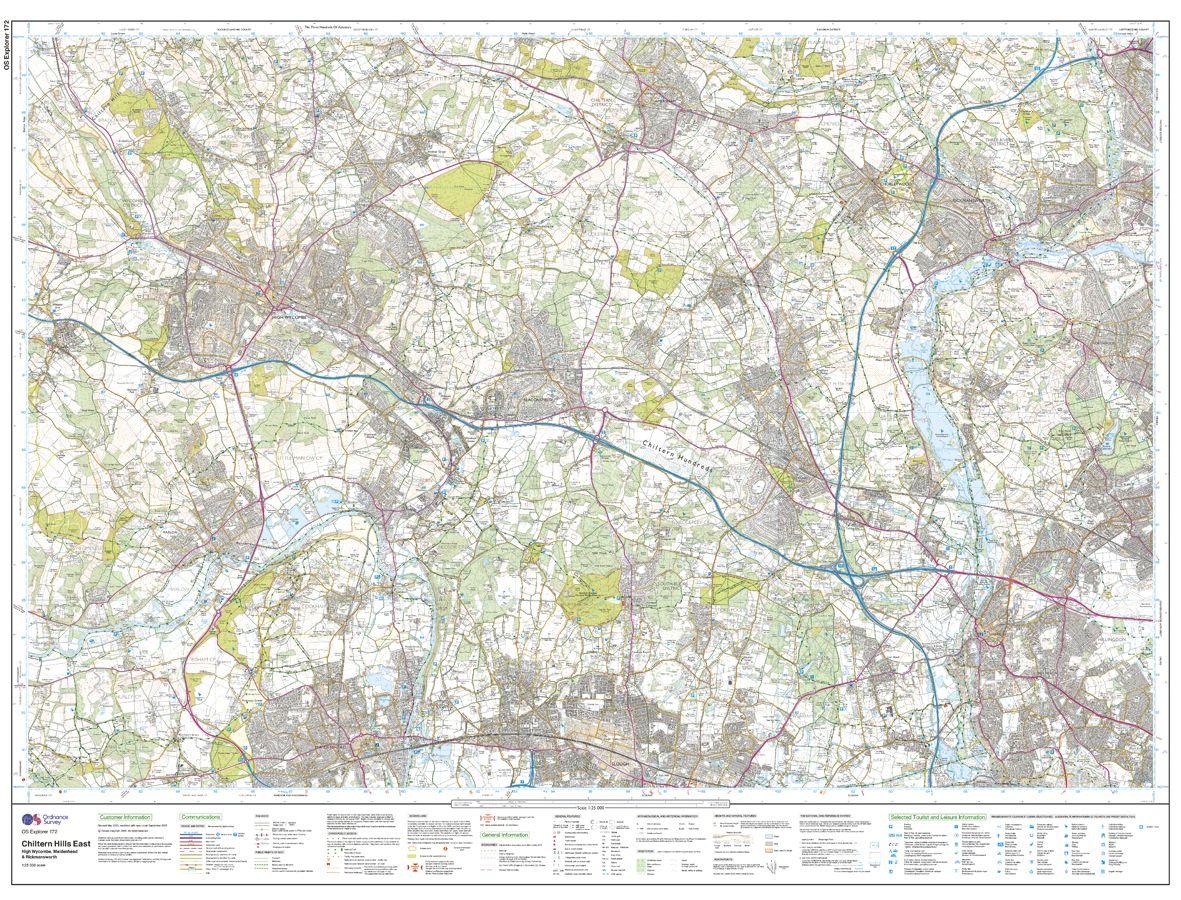

When I first decamped from London to the Chilterns I bought the relevant Ordnance Survey maps of the area, poring over them endlessly: tracing the line of the disused arm of the Grand Union Canal to Wendover; marvelling at the wooded hills over which the Ridgeway path wended its way; wondering how much the construction of the A41 must have changed the development potential of towns like the one I had moved to.

On the outskirts of a village nearby I spotted a circular path, apparently following the outline of some sort of embankment. I must, I thought, go to see it.

But for years I failed to act. It was a bit out of the way, there was no particular reason to go and there were lots of other paths to walk much closer to home. It was only when I read in a locally produced book about Cholesbury Camp, an Iron Age hill fort, that I put two and two together.

I got my map out once again and finally made my way to that circle of green dashes, where I found the extraordinary remains of those prehistoric ramparts, on which giant beeches and oaks now grow.

Red kites wheeled above, and in the plateaued centre of the ‘camp’, horses grazed – perhaps as they had done 2,000 or more years before, when earlier generations of local people trod this ground.

Having spent so long being intrigued by a feature on a map, I now find myself drawn back to the site of an ancient Chiltern community again and again, dragging my children around the earthworks in all weathers as we seek to root ourselves.

In the end, the joy of maps is not that they tell you how to get to a pre-planned destination – but that they can tempt you to places you have no particular need to visit, and to which you might nonetheless return many times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments