Unethical gold: How Dubai is complicit in exploiting West Africa’s youth in Mali

The Emirate state’s pursuit of being ‘biggest and best’ is fuelling a chain reaction of trafficking children and women toward Mali’s small-scale artisanal gold mining towns, writes Paddy Dowling

In recent years, the United Arab Emirates has positioned itself as one of the world’s fastest developing gold trading hubs. While its economy has always been underpinned by oil, tourism and real estate and property, gold has now become one of the largest exports for the emirate state of Dubai.

Dubai’s mission to future-proof life after oil may not be to everyone’s taste, but it has to be admired. Millions of travellers flock there each year to admire its marvels: the world’s tallest skyscraper, vast shopping malls, gold souks and so forth. They approve of the state’s ability to twist, pivot and dazzle. The performances are faultless. Dubai is tenacious, innovative and daring. But at what cost?

The UAE’s rapid rise up the global gold import rankings to fourth (trailing Switzerland, China and India) has ostensibly been accomplished by imposing minimal restrictions on imports. Often little or no proof of origin is required, and no questions are asked as to whether taxes have been paid to countries that have produced the imported merchandise. Mali is one of these countries, Africa’s fourth-largest producer of gold.

Ousmane, 58, has been part of Mali’s gold-producing inner sanctum for more than 25 years and explained how industrial mining companies in Mali did not sell to the UAE.

We were all told that within three months of working at the mines, we could earn enough to buy a motorbike, but it’s not that easy. Even if I work hard, I can only earn around £360 per year

“Whereas industrial mining remains heavily regulated, Mali’s artisanal small scale mining (ASM) gold sector is entirely different. It’s a black market trade in gold, subject to every type of exploitation, women and children faring worst.”

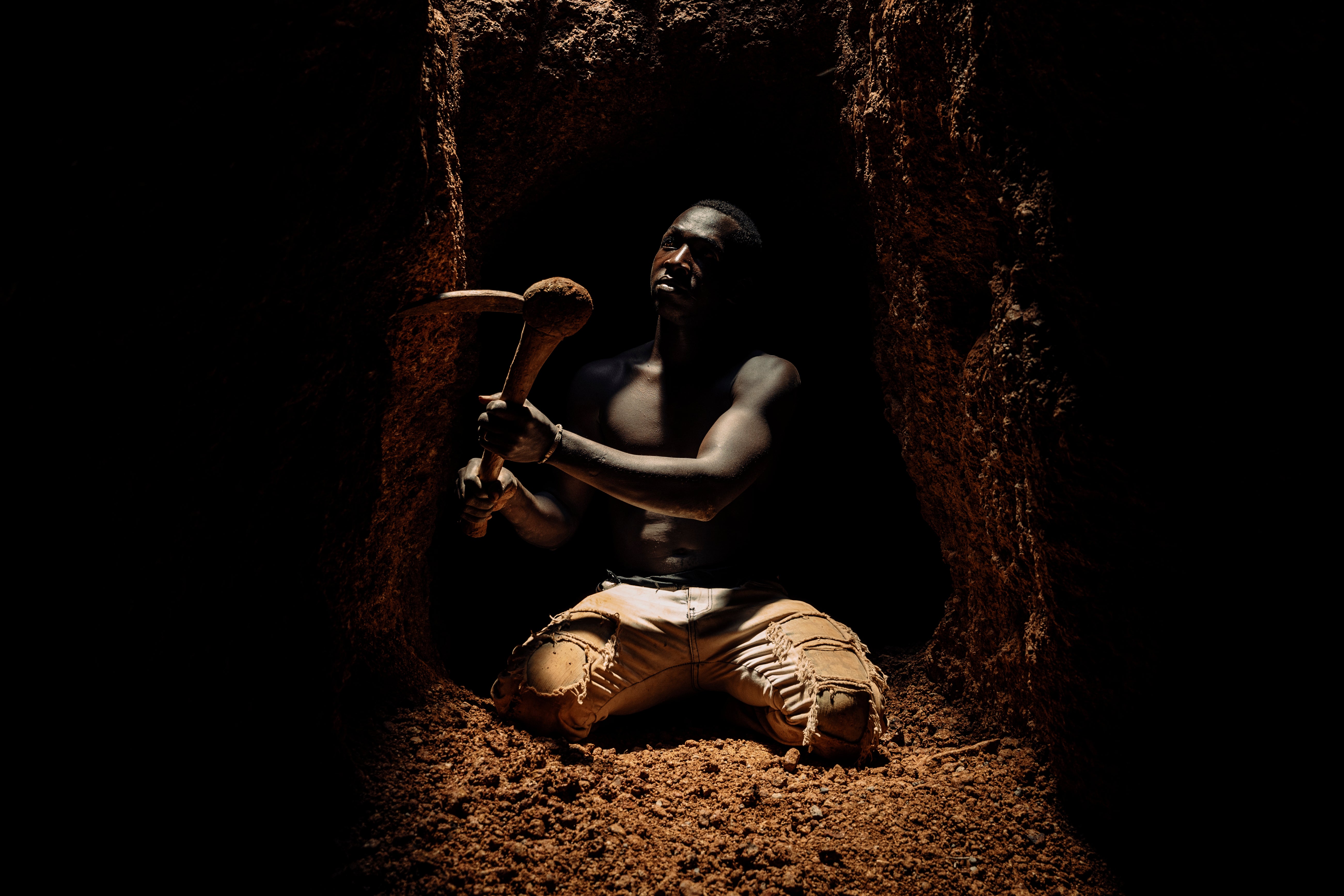

For the unenlightened, ASM is subsistence – mining is done by independents, often by hand, involving children and in appalling conditions.

The United Nations’ Commodity Trading Data platform (Comtrade) recorded the UAE having imported $1.52bn in gold from the West African nation in 2016, with confirmed totals from Mali’s government registering only $216m being exported. By 2019 the UAE had imported $3.3bn. According to Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC) Dubai’s share was 80 per cent.

Ousmane continued: “The illicit trade of Artisanal gold is shrouded in secrecy. Gold is smuggled out by unregistered dealers, hand carried, without export documents but with the complicity of airport staff and police authorities, each taking their cut. Mali’s artisanal gold is all destined for Dubai”.

In a backstreet dealing room hidden from view on the third floor of an old souk beyond a maze of mirrored corridors, four armed youths rose to their feet, filling the room and were told to stand down.

A young Malian, one of the largest dealers in Bamako, withdrew his head from behind the door of a large steel safe with his phone held horizontally to his ear, talking loudly in Bambara (Mali’s local dialect).

He slapped five solid shrink-wrapped six-inch-tall blocks of 10,000 Communauté Financière Africaine (CFA) franc banknotes (worth £13) down onto his oversized desk. Another employee, who buzzed into the fortified office, carried a perforated aluminium plate full of gold. He exchanged this for the cash, which he stuffed into an old black bin liner, and left.

This choreographed dance continued. Gold came in, and money went out.

When asked to see the gold bars for export, the dealer laughed and explained: “You missed them, our transporters left for Dubai yesterday, 40 kilograms every week. Dubai wants exclusivity on every grain and every gram. As much as we can provide.”

Mali has endured extreme instability since 2012, with ethnic and tribal conflicts, rebel groups vying for territories in the centre and north, deep-seated corruption in past governments, military coups and the rise of Islamic insurgency across the entire Sahel region. The aggregate effect has plunged Mali into severe multidimensional poverty, now ranking 184 out of 189 countries according to the United Nations Development Programmes (UNDP) and Human Development Index (Human Development Report Office 2020).

The escalating conflict in Mali has also closed 1,532 schools, leaving approximately 400,000 children with no access to education and vulnerable.

Amadou, 16, originally from Segou, arrived at a mining town near the Guinea border, 120km from Mali’s capital Bamako, three years ago, hoping to change his family’s fortunes.

“We were all told that within three months of working at the mines, we could earn enough to buy a motorbike, but it’s not that easy. Even if I work hard, I can only earn around £360 per year”. His salary is equivalent to 99 pence per day, a rate well below the UN’s extreme poverty level of £1.37.

In an area that covers 400 square kilometres, children as young as 12 dig vertical shafts up to 16 metres deep and then horizontally as far as 200m, often passing abandoned tunnels radiating like an underground interconnecting spider’s web. The shafts are unsupported, hot and airless. The children work in the dark, emerging from the hundreds of shafts to rest, drenched in sweat. Their clothes and skin were painted with the rich ochre colours of Africa’s gold-bearing soils.

Traditionally activity at ASM sites during rainy seasons would reduce to a trickle, as the dangers of pit wall collapse force many to return to the fields and work in agriculture. However, due to the increased demand from buyers and the pressures from the organised gangs that brought them there, this is not an option for many children.

Emanuelle, 12 years old from Burkina Faso, explained: “I came here like most of us, to support our families. Sometimes we get paid a salary and sometimes we don’t. I had hoped to return home during the rainy season, but I was brought here by car, and I have to repay my debt before I can leave”. Emanuelle earns around £14 per month, which accounts for just 47 pence a day.

Pascal Reyntjens, chief of Mali mission at the International Organisation for Migration, said: “The resilience we see in Mali has turned to resignation, a complete absence of hope. Artisanal gold mining is undoubtedly producing labour abuses, exploiting the vulnerability of people who plan life one day at a time”.

“The trafficking of boys from Burkina Faso to ASM sites in Mali is just a classic technique where children are often subject to debt bondage for transport, somewhere in the region of half a million CFA [£650].”

Exploitation does not stop with children, it extends to women. A steady flow of girls from Nigeria are tricked and trafficked towards Benin, given new identities and smuggled to Bamako under the guise of employment in the capital’s many hotels and restaurants”, IOM’s Chief of Mission told The Independent.

“On arrival in Mali, they are asked to reimburse their costs at around 1.2 million CFA [£1,560] and sent to the brothels at mining sites in order to repay their debt. There are currently around 4,000 protected victims of sexual trafficking in Mali from Nigeria”.

The London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) is an independent body founded to ensure responsible sourcing to protect the integrity of the whole gold supply chain. Its head of responsible sourcing, Alan Martin, said: “Governments of those countries who import ASM gold are aware of the vulnerabilities, and so are their buyers. However, these challenges are not unique to just Dubai. Importing artisanal gold presents a whole litany of issues, and the responsibility falls on the shoulders of many”.

The laundering of artisanal gold through Dubai’s gold souks, only to be resold to one of the states’ 11 refineries as “scrap”, re-emerging in the supply chain untainted, provides enormous challenges for consumers seeking to purchase responsibly sourced goods. This is further exacerbated by the fact that Mali is used as a gateway to UAE gold markets by African nations looking to fund conflict.

The UAE’s Ministry of Economics, via the DMCC, was asked to comment but is yet to respond.

Dubai’s current mechanism to import artisanal gold contravenes no legal framework. There is, however, a moral issue. Through its lack of due diligence on its supply chains, which go right back to the mining sites, the country is relying on apparently plausible deniability.

Whatever concessions and efforts Dubai is currently making to be “cleaning house” over responsible gold sourcing, in reality, is not working. Today, the pressures on Mali’s dealers to meet the bottomless state quota are coming at a cost. A human cost.

The haunting stares of the boys from Burkina Faso lined up, shovelling gold-bearing rock into crushers with robotic fashion, toiling under the midday sun, obscured behind plumes of noxious diesel soot, offers a stark reminder to all consumers – to ensure that the gold they purchase does not come at a cost which importing nations are still prepared to overlook. Otherwise, consumers are as complicit as the human traffickers, unregistered dealers, smugglers, transport mules, gold cartels and those countries who believe they are beyond reproach, yet who are importers.

*All names have been changed to protect the identity of the individuals

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments