Prisoners locked down during the war used intellect and creativity to survive

The British Isles’ last lockdown – when German Jewish refugees were interned on the Isle of Man – sparked a creative and intellectual renaissance after the war. During their confinement these emigres founded a university, theatre, gallery and an orchestra, reports William Cook

Many Britons have been keen to follow the Queen in evoking folk memories of the Second World War. From the tabloids to the twitterati, “Blitz Spirit” has become a popular rallying cry in the battle with coronavirus. Fair enough. If it works for you, good luck to you – whatever floats your boat. In times like these we all need stories that inspire us to keep going, to keep calm and carry on.

As someone whose two grandfathers fought on opposite sides in the Second World War, I’ve always felt a bit conflicted about this sort of thing (my English grandfather lost a brother at El Alamein – my German grandmother lost a brother on the Russian Front). However, even I can see that for a lot of people, the war has become a useful reference point in our struggle against the virus. Sure, it may be inadequate and imprecise, but it’s still a handy shorthand. Why, even Angela Merkel has harked back to it, calling Covid-19 the greatest challenge Germans have faced since the Second World War.

For those brave Britons on the frontline (doctors, nurses, care home workers, transport workers…), the Blitz is probably a fitting metaphor. For layabouts like me, sat at home, a different war story springs to mind. As someone with a German passport and a British passport (and deep feelings for both nations), I’ve been drawing inspiration from the oft-forgotten tale of those “enemy aliens” who were interned on the Isle of Man during the war.

For me, learning how those persecuted people coped with a far more arduous form of lockdown has been a valuable lesson. Maybe it’ll inspire you too. Like a lot of war stories, it’s a tale of courage and fortitude, but what makes it special is that it demonstrates the importance of intellect and creativity in a crisis. These internees showed that in tough times, when you’re cut off from society, the life of the mind isn’t a luxury – it’s essential. They transformed their internment camps into virtual universities. And now, a lifetime later, their achievements have suddenly become topical again…

When Britain went to war with Germany, in 1939, around 80,000 Germans and Austrians living in Britain became classified as enemy aliens, including 55,000 Jewish refugees. Initially several thousand were interned, including over 500 Jews. In May 1940, after Dunkirk, when a German invasion suddenly became a far bigger threat, a further 8,000 Germans and Austrians were interned. “Collar the lot,” said the new prime minister, Winston Churchill, indifferent to the fact that many of these enemy aliens had lived in Britain for decades, and that many of the more recent immigrants had fled here to escape the Nazis (some had even been in concentration camps). No matter.

More than 7,000 were subsequently shipped to Canada and Australia (tragically, hundreds died when one of these ships, the SS Arandora Star, was torpedoed by a German U-Boat). Those who remained were interned in the British Isles, mainly on the Isle of Man. In June 1940 Italy declared war on Britain, and so 4,000 Italian residents were added to the list. As the conflict intensified, the number of internees on the island soared, their numbers bolstered by Hungarians, Romanians, Bulgarians, even Fins. Knockaloe Internment Camp, near Peel, just one of six camps on the island, ended up with 23,000 inmates.

The Isle of Man is a charming place (my English grandparents used to live there and I spent many happy childhood holidays there) but being taken there against your will in wartime was clearly a very different prospect. “Very few of us even knew that there was an island in the Irish Sea, and all sorts of rumours arose about our destination before we actually docked at Douglas on the Isle of Man,” remembered Freddy Godshaw, a German Jewish refugee who was interned, along with his elder brother, Walter, and their father (who’d recently been released from a Nazi concentration camp). “Armed guards escorted us with fixed bayonets to a square in the centre of Douglas. A double row of barbed wire had been erected around three streets.”

Women were taken to a separate camp, in Rushen, in the south of the island. The regime in Rushen was more relaxed than in the five male camps on the Isle of Man. Here, there were no barbed wire fences and no soldiers standing guard. Female inmates were free to stretch their legs outside the camp, rather like lockdown today (there was little chance of escape – Britain and Ireland were both a long way away). Nevertheless, inmates were left in no doubt that their liberty had been curtailed, for an indefinite period. “When we arrived, we had pictures taken with our number on,” one internee, Hilda Wolfgang, told the BBC. “We already had the feeling we were criminals.”

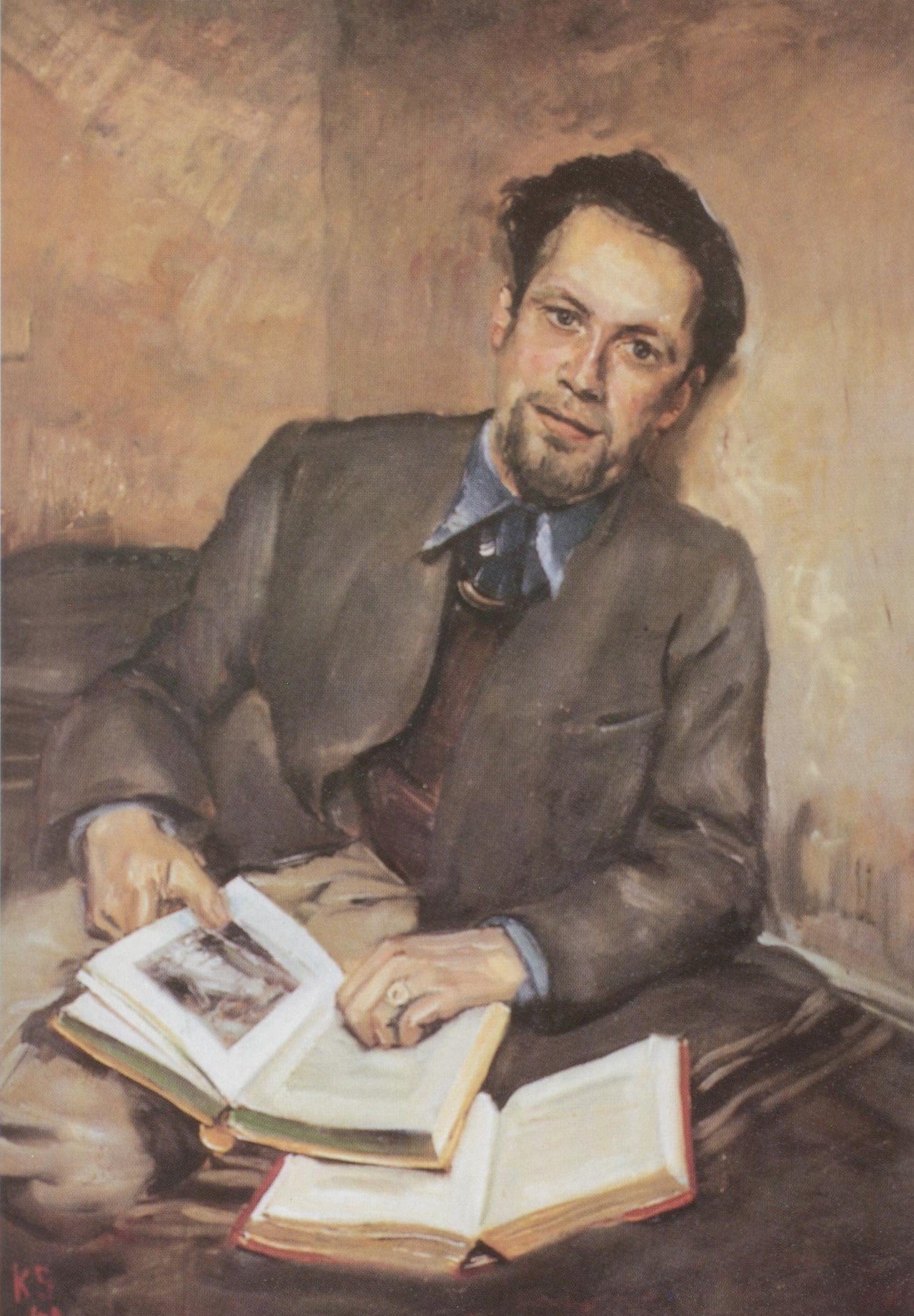

Musician and composer Peter Gellhorn taught music, conducted choirs and ensembles – and gave more recitals, he reckoned, than at any other point in his career

The male camps were more severe and spartan: better than being in a normal British prison, but imprisonment nonetheless. Unlike purpose-built British prisons, the accommodation consisted of requisitioned boarding houses, which sounds quite nice until you learn that only one room in each house was heated. Marooned in the middle of the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man is windswept at the best of times, and cold and wet in winter. The boarding houses were cramped and crowded, and conditions were rudimentary. A lot of inmates had to share beds. Yet these internees soon realised that self-improvement was the best way to preserve their sanity. Workshops were established for all sorts of crafts: tailors, watchmakers, toymakers… Inmates taught each other. Camps published their own newspapers, in German and English.

A good many internees were musicians, and many had brought their instruments with them. In Mooragh Internment Camp, in Peel, musician and composer Peter Gellhorn taught music, conducted choirs and ensembles – and gave more recitals, he reckoned, than at any other point in his career. He also wrote some wonderful music.

“There are several pianos, of which one will do for recitals, and I have given quite a few, alone and with string players,” he wrote to his friend and fellow composer Priaulx Rainer. “Since I came here I’ve written a piece for choir and strings, two studies for violin alone, and two pieces for strings.” Gellhorn’s piece for choir and strings was Mooragh, July 1940, set to a poem by his fellow inmate FF Beiber, first published in the camp newspaper, The Mooragh Times, and subsequently in an anthology called Stimmen hinter Stracheldraht (Voices behind Barbed Wire).

Hutchinson Internment Camp, in Douglas (the island’s capital), was also blessed with numerous musicians. Inmates staged regular concerts: German composers (Bach, Brahms, Beethoven) were especially popular. One group of internees formed the Amadeus Quartet, which became one of Britain’s leading ensembles after the war. The camp was also renowned for art and, above all, academia. This was where Freddy Godshaw and his brother Walter ended up (they’d narrowly escaped being shipped to Canada on the ill-fated SS Andora Star). There were dozens of academics interned here – Freddy counted over 50 professors among the 1200 inmates. “We soon had a timetable and lessons every morning.”

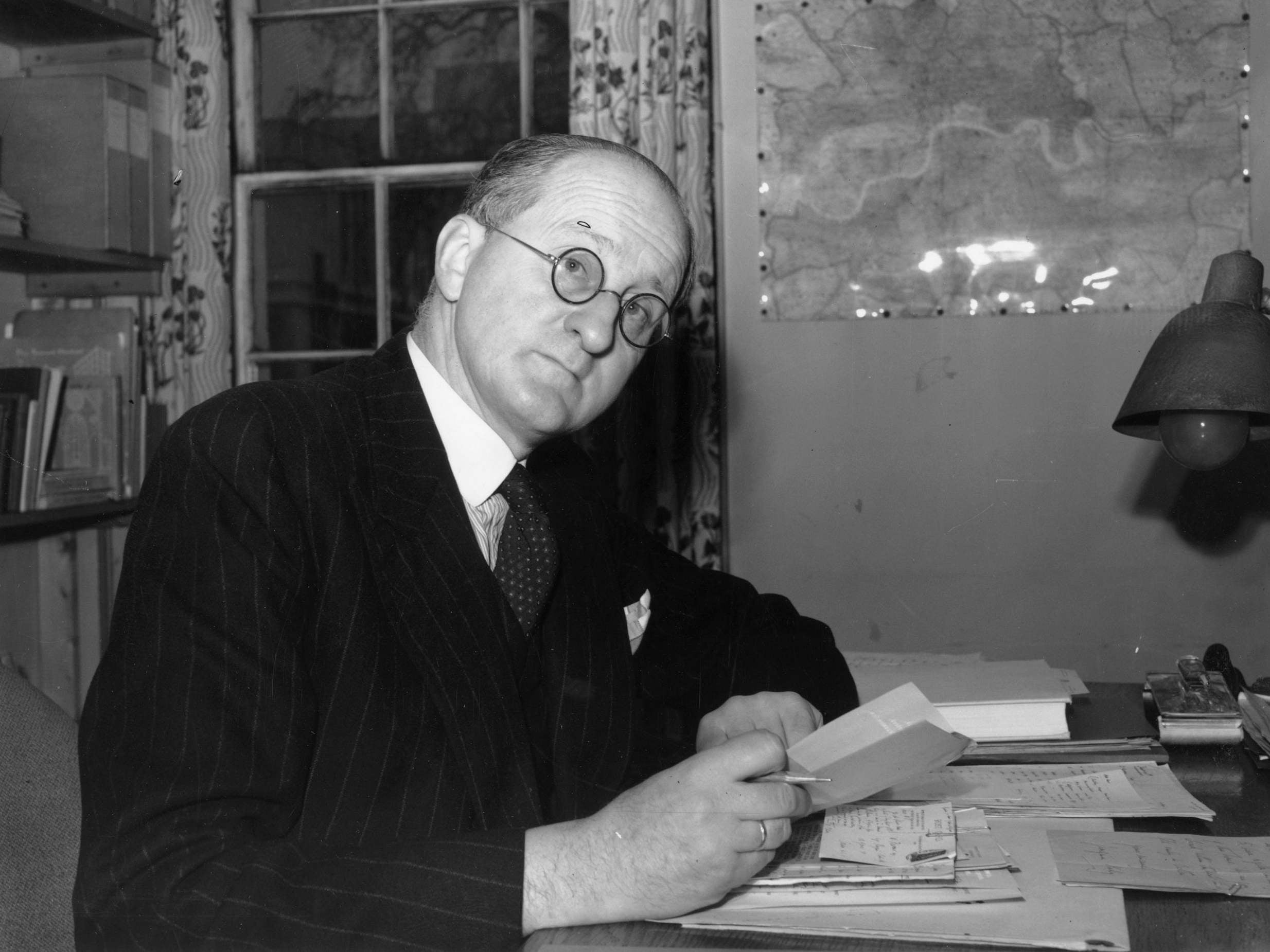

You could study virtually any subject you could think of (and quite a few you couldn’t). “A typical week’s worth of activities in October 1940 included history lectures on Metternich, the rise of English democracy, church history, Medieval culture and the British Empire; science lectures on bacteriology, physical chemistry, mathematics and aspects of nutrition; a philosophy series on the Ancient Greeks; lectures on French and German literature, and various literary and musical recitals,” writes Daniel Snowman in his absorbing, groundbreaking book, The Hitler Emigres – The Cultural Impact on Britain of Refugees from Nazism.

For Fred Uhlman, a German Jewish lawyer cruelly separated from his pregnant wife, this lavish curriculum was an invaluable distraction. Indeed, there was such a wealth of lectures on offer that inmates were often spoilt for choice. “What if Professor William Cohn’s talk on Chinese Theatre coincided with Egon Wellesz’s introduction to Byzantine music?” mused Uhlman. “Or Professor Jacobsthal’s talk on Greek literature with Professor Goldmann’s on the Etruscan Language? Perhaps one felt more inclined to hear Zunz on The Odyssey or Friedenthal on the Shakespearean stage?’

Drama was also an important respite. Highlights included a dramatisation of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice & Men, and a homosexual version of Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, entitled Romeo & Julian. In an era when homosexuality was an imprisonable offence, this was brave and radical (homosexuality was only decriminalised in Britain in 1967, and not until 1992 on the Isle of Man). For others, learning languages was a precious release. There were courses in English, French, Spanish, Greek, Russian and Japanese, all taught by fellow inmates. Classicists could even brush up on their Latin.

That’s pretty much what those internees were doing. Nobody was paying them to play music or paint pictures or publish newspapers or put on plays. They did it for the fun of it

Art materials were in short supply, but this didn’t deter the camp’s artists. Wrapping paper from parcels was recycled as drawing paper. Linoleum flooring was pilfered to make lino cuts, and oil from sardines tins to make oil paint. Despite such privations, these artists had far more creative freedom in internment than they’d enjoyed in Nazi Germany. Modernist genres such as Expressionism and Primitivism, denounced as “degenerate” in Nazi Germany, flourished behind the barbed wire. The most well-known “degenerate” artist in the camp was the Dadaist artist Kurt Schwitters, who produced hundreds of works during his internment. His portraits of his fellow inmates were especially prized. Freddy Godshaw sat for him, as did his brother, Walter. Freddy treasured these sketches, and kept them throughout his life.

For Schwitters, art was a great escape – a way to forget about the frustration of confinement. “He worked with more concentration than ever, to stave off bitterness and hopelessness,” said his son, Ernst, who was interned with him. “For the outside world he always tried to put up a good show.” However, as we’ve discovered during our own confinement, seclusion can be hard to bear. Under the strain of isolation Schwitters’ epilepsy, dormant since childhood, flared up again. “In the quietness of the room I shared with him,” remembered Ernst, “his painful disillusion was clearly revealed to me.”

Schwitters lobbied the authorities, imploring them to set him free: “As an artist, I cannot be interned for a long time without danger for my art.” Yet his entreaties were in vain. Long after every other artist had left the island, he remained in captivity. Even so, he remained stoical. “I am now the last artist here – all the others are free. But all things are equal. If I stay here, then I have plenty to occupy myself. If I am released, then I will enjoy freedom.” Have you ever come across a better mantra for enduring lockdown?

Schwitters was finally released in November 1941, and moved to London. At last he had his freedom, but it wasn’t an easy emancipation. He had several exhibitions in London, but he sold very little. Now was not a good time to be exhibiting avant-garde art. In 1943, he learnt that his home and studio in Hanover had been destroyed by Allied bombers. In 1944 he suffered a stroke. In 1945, he moved to the Lake District, where he recreated his old studio, in a barn in Elterwater. In 1946, he had another stroke. On 7 January 1947, he was granted British citizenship. On the 8 January, he died.

For me, Schwitters’ story encapsulates this internment saga, and shows what we can learn from it. For these blameless men and women, internment was a catastrophe, an awful infringement of their civil liberties. And yet they made the best of it, making order out of chaos. Schwitters was particularly affected, yet he was particularly productive during lockdown. Without adversity, without suffering, art has no meaning. Happiness writes white.

So will lockdown turn us into great artists, great novelists, great composers? Will you finish that unfinished novel, or write that musical you always meant to? Maybe, but for most of us that’s not what creativity is about. If you’re anything like me, it’s about trying to live from day to day with a bit more passion and imagination – trying to make each day a bit more like the life we dreamt about when we were kids.

I’ve had good days and bad days during lockdown, and the bad days have been bloody awful, but on the good days I’ve had fleeting glimpses of something special – a different way of living, closer to the way I used to feel. Have you felt it too? Daft stuff my wife and I have done together, fun times I’ve shared with my teenage children... In these listless times I’ve been terribly bored, so I’ve found new things to do, and then I’ve remembered what I used to do for fun when I was young.

That’s pretty much what those internees were doing. Nobody was paying them to play music or paint pictures or publish newspapers or put on plays. They did it for the fun of it, because it was the best way to stay sane. Those good times you’ve had in lockdown, in spite of everything, are just as creative as any artwork. And if you can do it here and now, in lockdown, you can do it anywhere. Like those internees, you can use what you’ve achieved in these tough times to build a better life.

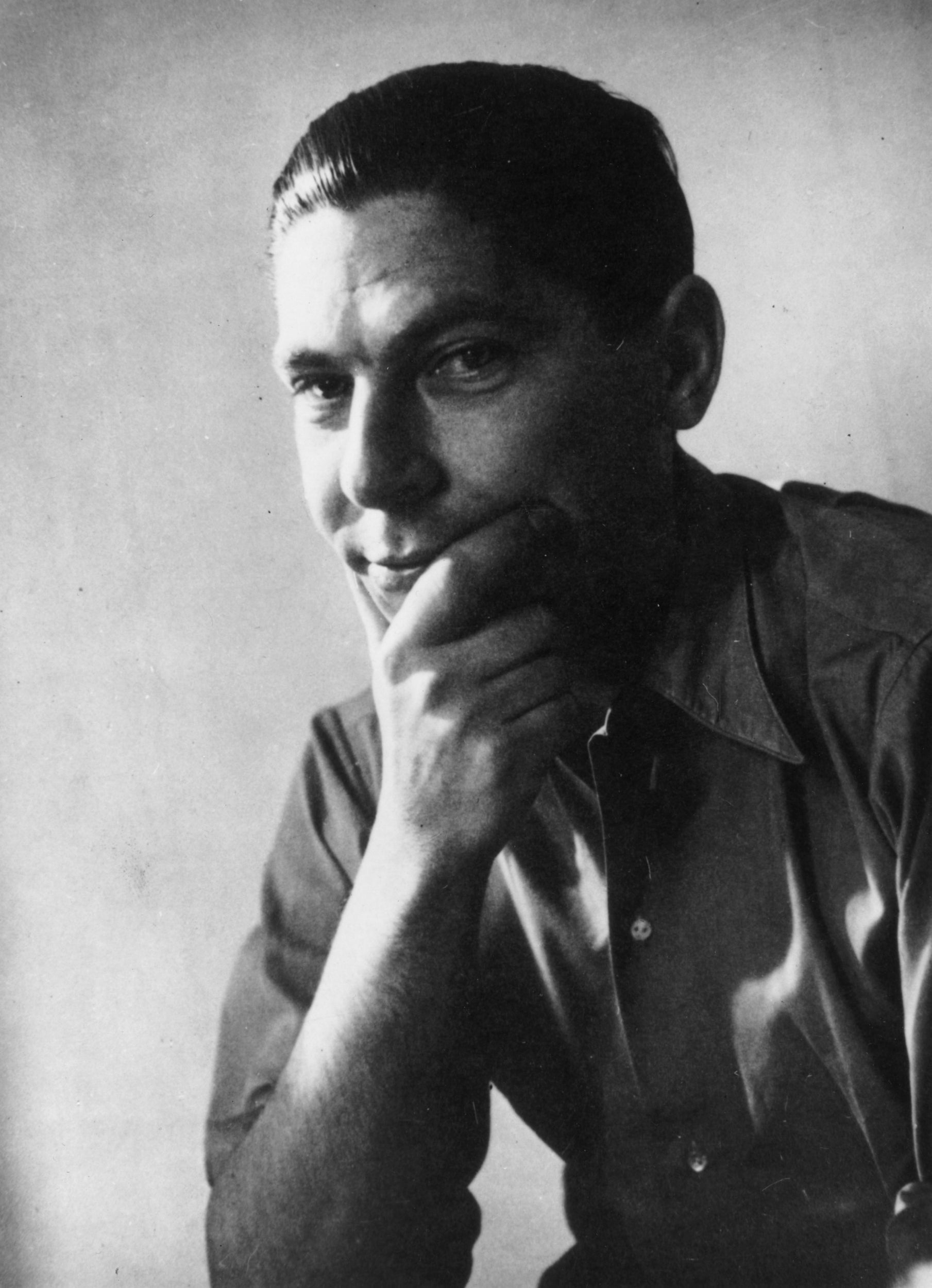

Those Germanic refugees were transformed by their internment. After they were released they changed postwar Britain for the better. Kurt Jooss (dance), Arthur Koestler (literature), Hans Keller (music), Claus Moser (opera), Nikolaus Pevsner (architecture)… The list goes on and on. After the war nobody wanted to go back to the way things were before, and after lockdown nor will we. My idea of a more creative life is about living with a lot less stuff and a bit less money if needs be, and a lot more time to do the things I really want to do. That was their idea, too. What’s yours?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

6Comments