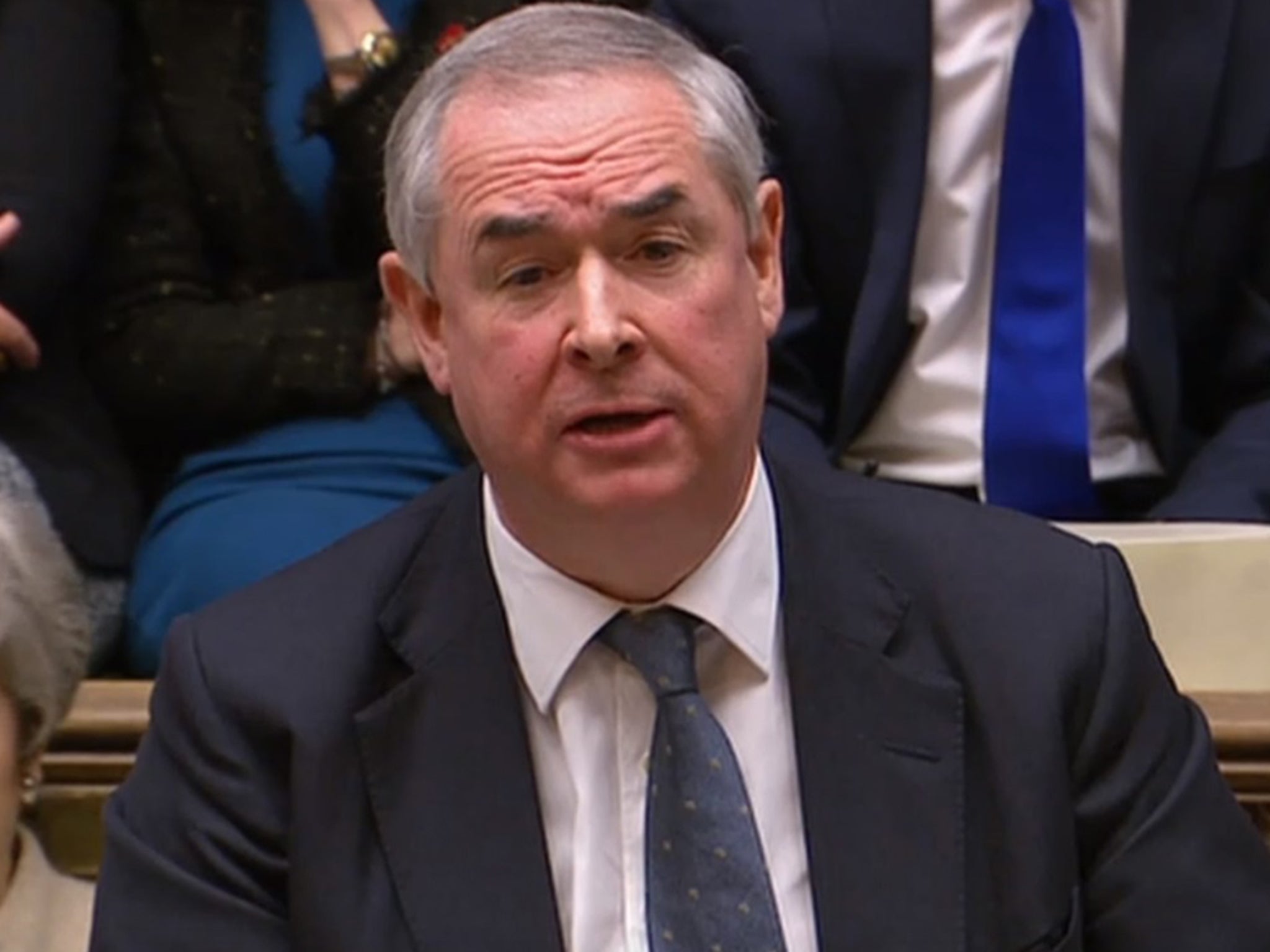

Sir Geoffrey Cox MP: From lawyer to Tory MP to tabloid press sensation

Sean O’Grady considers Sir Geoffrey Cox’s career trajectory, from popular Tory MP to making the headlines for all the wrong reasons

It’s a funny old world isn’t it, as someone once said. In the latest condemnation of his alleged conduct, a Conservative colleague of Sir Geoffrey Cox MP calls him “an arse”, which is probably not defamatory. Sir Geoffrey, it seems, has become synonymous with a certain sort of attitude, a certain arrogance, and is a net negative for the Tories’ poll ratings. He has taken over from Owen Paterson in the sleaze headlines. No 10 has let him hang in the wind.

Yet not so very long ago, Geoffrey Cox was dominating the headlines in every paper, all over social media, the very focus of the nation’s attention and provoking intense reactions in Conservative circles – and for all the right reasons. For a few days in October 2018, he was the darling of the Tory press. There was overexcited talk about the then attorney general being the next party leader and prime minister.

The activists, starved of confidence after the previous year’s disastrous election, were ecstatic about Sir Geoffrey’s bravura performance at the Conservative conference. It was the first time they had tasted the rich fruity baritone, the baroque delivery, and his near-erotic display of erudition. His 12-minute speech at the Birmingham arena was billed as a mere warm-up act for the prime minister Theresa May. In the event, he stole her limelight and almost her job. Not so difficult, true, but he also displaced Boris Johnson, then a marginalised and unhappy former foreign secretary, something that must have hurt and perturbed Johnson in equal measure.

He was called the Tory Gandalf, the Mufasa of Brexit, the “breakout star” (Daily Mail). The Telegraph concluded: “Move over Boris Johnson – the Conservatives have a new Brexit champion: Geoffrey Cox QC”. Mixing jokes and easy references to The Rolling Stones with some hard legal truths, Cox enchanted his audience by extemporising around the stage in a mash-up of Brian Blessed, Tom Baker and Patrick Stewart. The highlight, surely a treasured moment still for Sir Geoffrey, was a passage from John Milton’s paean to free speech, Areopagitica:

“Methinks I see in my mind a noble and puissant nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep, and shaking her invincible locks: methinks I see her as an eagle mewing her mighty youth, and kindling her undazzled eyes at the full midday beam”.

After the rapturous applause died down and May was allowed her anticlimactic go, she asked if she could borrow Sir Geoffrey’s voice, an uncomfortable reminder of her coughing fit the previous year. The suddenly enthused activists took to Twitter to ask each other where the Conservatives had been hiding their megastar. Sadly, after the revelations about his vast earnings and the time he spent practising law in the British Virgin Islands, they’d now rather like to send him back to his hiding place. And he has gone a bit quiet lately. The Daily Mirror has put up “Wanted” signs in his constituency, and the Daily Mail is asking, “Where IS Geoffrey Cox?” The rumour is he’s somewhere comfortable in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

The answer, of course, back in 2018, was that Sir Geoffrey had been “hiding” in plain sight in the House of Commons, representing the seat of Torridge and West Devon since 2005, having first tried to win the seat from the Liberal Democrats in 2001, but never giving up the lawyering. In between his tilts at a political career he was appointed a Queen’s Counsel, aged 43, after about 20 years at the bar. He spent some time on the environment select committee and on the standards and privileges committees.

In an augury of what was to follow, he resigned from the Committee of Privileges in 2016, because he’d made a late registration of £400,000 in legal fees. It was, and is, not unusual for him to be acting on behalf of clients as a barrister, and his clientele has included the government of the British Virgin Islands, the state of Mauritius, and various wealthy individuals and entities in the world of business and finance. He is no stranger to clients with links to so-called tax havens, and they’re not popular things.

In his defence, it has to be added that justice demands every client deserves a fair hearing, competent representation, and (in the BVI Commission of Inquiry, which is not a trial) sound advice. As he put it in his recent statement: “This is not to ‘defend’ a tax haven or, as has been inaccurately reported, to defend any wrongdoing but to assist the public inquiry in getting to the truth. No evidence of tax evasion or personal corruption has been adduced before the inquiry and if it had been, that person would have been required to seek their own representation.”

In the kind of high-stakes commercial, as well as the more political, cases Sir Geoffrey takes on, fees can be very high, and he is, in his own immodest words, a “senior and distinguished professional in his field” (including at Thomas More Chambers). In his position, he can hardly avoid earning half a million a year just by getting out of bed and taking a couple of phone calls. He claims to do a 70-hour week (no reason to doubt it), and “always ensures that his casework on behalf of his constituents is given primary importance and fully carried out”.

As far as Sir Geoffrey is concerned (he was knighted as is traditional on appointment as attorney general), it’s up to his voters as to whether they like how he allocates his time. Given that his first majority of 3,326 had mushroomed to 24,992 by 2019, they have seemed contented enough. If there were to be a by-election it’d be a bit of a long shot for the Liberal Democrats, but they are an independent-minded bunch down Tiverton way.

Indeed, Sir Geoffrey’s surprise emergence from relative obscurity – “I did not expected a frontline political career” – was almost accidental. Some are born great, some achieve greatness, some have greatest thrust upon them: in Sir Geoffrey’s case, by being the only Brexit-supporting QC in the Commons when May decided she needed a heavyweight attorney general to bring some heft to the Brexit talks.

Sir Geoffrey tells the story of how he got the job, on a side hustle at that moment, as follows: “I had been sitting in a courtroom on 9 July 2018 when the mobile phone buzzed. Generally, one doesn’t have one’s mobile phone on in a courtroom, but mine was on, and I recognised the number; it was the number of the chief whip of the time. Even I, hitherto impervious to the blandishments of whips generally, and quietly practising at the bar while serving my constituents on the back benches, felt that I should take that call, and whispering to my junior that I had to take the call at about 4 o’clock, by 9 o’clock I found myself attorney general.

“I had no expectation of a frontline political role.”

Nonetheless, Sir Geoffrey viewed this appointment as “the pinnacle of my career” and the only government job he’d be willing to take at that stage (aged 58). He was to enjoy mixed success.

In Sir Geoffrey’s formulation, the job of Her Majesty’s Attorney General for England and Wales “combines a necessary and important political element but also is made for, and occupied by, someone who has spent a good proportion of their life in the practice of the law”. He is indeed part government lawyer, and puts the law first, but he is also an aggressive partisan politician, which is unusual in a law officer.

Sir Geoffrey was not the first to find it challenging. To his credit, on key occasions, both in post and after, he has put his supreme loyalty to the law first, despite his round abuse of political opponents. This could, and did, prove critical. In 2018, and again in 2019, he refused to oblige May with helpful advice on her “backstop” Brexit protocol, which would have left the whole of the UK in the EU customs union should a new trade deal fail to solve the Northern Ireland border issue. He was as helpful as he could be, arguing that failure was highly unlikely, but in the final analysis he advised that the May deal could not be unilaterally cancelled by the UK – not lawfully, at least. It was pretty much May’s political death warrant.

In much the same vein, Sir Geoffrey later told Johnson bluntly that he had to write a letter to the EU requesting an extension to the UK’s Brexit leaving date, for the simple reason that parliament had just passed a law explicitly requiring him to do just that. Sir Geoffrey refused to countenance Johnson breaking the law, so Johnson resorted to a childish tactic of not signing the letter, and added another one stating the opposite – but the date was postponed all the same. Later Sir Geoffrey was to declare that it is “not acceptable for an attorney general to massage and improve his advice for the purposes of party politics”.

That episode probably didn’t endear him to the prime minister, and, reportedly, No 10 began to think that Sir Geoffrey wasn’t “a team player”. It was Johnson who sacked him in the reshuffle that fell just before the Covid lockdown. As his resignation letter pointedly stated, Sir Geoffrey left at the request of the PM, and he was said to be looking grumpy after his interview with Johnson in the prime minister’s rooms in the Commons. Equally sharply, Sir Geoffrey reminded everyone that he had always offered “candid and independent” legal advice, code for “unwelcome advice”.

Unlike, say, his predecessor in the Blair government, Lord Goldsmith – who changed his advice on the issue of the legality of the Iraq war, allegedly for political reasons – commentators suggested that Sir Geoffrey wouldn’t alter his legal advice for political expediency. In due course, while out of office, Sir Geoffrey also honourably objected to the Internal Market Bill, which famously threatened to abrogate parts of the withdrawal agreement recently signed by the UK if they were inconvenient, especially in Northern Ireland.

You may recall that this was the time when the Northern Ireland secretary Brandon Lewis, amazingly, stated at the despatch box that international law would be broken, but only in “a very specific and limited way”. This was intolerable to Sir Geoffrey, and he refused to vote for the bill. Sir Geoffrey, who should know, said that Johnson knew what he was signing, and that the British could not “renege” on a solemnly agreed treaty with “known, unpalatable but inescapable, implications”: “What you can’t do is break the law.”

His sacking and subsequent estrangement from the leadership was somewhat ungrateful, not to say tragic. Sir Geoffrey had, after all, backed Johnson’s early prorogation of parliament that was later overturned by the Supreme Court – “bad” advice. He had also been, within the limits of the law, as effective a Brexiteer as anyone could be, stemming from his “strong, intellectual conviction of the importance of Brexit”. As with his barnstorming conference speeches, his Commons performances had an unusual galvanising effect, and he is one of those rare parliamentary performers who actually thrive on heckling, his baritone voice capable of punching through the jungle din. He knew how to make the MPs think, back in those turbulent, chaotic, groundhog days. In chart terms, he had two smash hits – one when he was in May’s group:

“A litigant in court who was dependent upon having concluded a contract on the basis of EU law and then found themselves suddenly having the rug pulled from under them, not knowing what their legal obligations were, would say to this house, ‘What are you playing at? What are you doing? You are not children in the playground. You are legislators’ ... We are playing with people’s lives.” (January 2019)

And, eight months later, for the Johnson band:

“this parliament has declined three times to pass a withdrawal act to which the opposition had absolutely no objection ... We now have a wide number in this house setting their face against leaving at all. When this government draw the only logical inference from that position, which is that we must leave therefore without any deal at all, they still set their face, denying the electorate the chance of having their say in how this matter should be resolved.

“This parliament is a dead parliament. It should no longer sit. It has no moral right to sit on these green benches”. (September 2019)

That peroration was memorably described by The Independent’s sketchwriter, Tom Peck:

“At this point, he began almost to orbit the despatch box. He jabbed his finger with such force it seemed to drag him four feet in every direction it went. It was like watching that old ‘haunted tea towel’ trick with the hidden spoon, as he chased his hyperextended digit all around the room.

“I cannot recall a solo performer covering such a wide area since Kanye West headlined the Pyramid Stage.”

Now it feels very much as though it is Sir Geoffrey’s political career that is dead, or at least, in a Pythonesque state of repose. The latest briefings from Downing Street declaim Sir Geoffrey for being “a lawyer first and an MP second”, something Sir Geoffrey would probably think a compliment. A lawyer all his life, he qualified for the bar in 1982, having studied classics and law at Downing College, Cambridge. But as well as being someone who reveres the law, as you’d expect, he is a real, traditional Tory.

He’s been characterised as a straightforward free-market Thatcherite, and he is genuinely evangelical about Brexit, “the greatest political mission of our time”. His is also a typical Conservative background. He comes from Wiltshire and a typically upper-middle-class family (his father was an officer in the Royal Artillery), and he went to a fee-paying school. Something of a country squire, there’s a photo of him, complete with waxed jacket, entertaining the Lamerton fox hunters in Devon, where he, his wife and three children have lived for many years. In his outlook, and indeed in his style, strength of personality and self-belief, he has much in common with the prime minister, and was once close enough to have introduced Johnson at the launch of the latter’s leadership campaign in 2019.

Had things panned out a little differently, then, and had he chosen always to put politics before law, Sir Geoffrey would still be in the cabinet, and would have been usefully absent from his legal duties and the Caribbean throughout the recent crises – an asset to the government, short as it is of real talent at the highest level. His oratory, described by one observer as “part Wolfit, part Sinden and part Brian Blessed”, would be flowing freely around the Commons.

He would also have been in prime position, it was said, to be put in charge of the “Constitution, Democracy and Rights Commission” promised in the 2019 Tory manifesto, which was intended, in crude terms, to tame the judges and weaken any remaining checks and balances on executive power. He’s in favour, for example, of having appointments to the Supreme Court vetted by a committee of the Lords and Commons, inevitably dominated by Tories. He still had some political use in him, though now it seems inconceivable that Sir Geoffrey will ever be rehabilitated. He awaits the inquiry of the standards commissioner and the standards committee on his alleged use of Commons facilities (his office) for private work. He’ll abide by their judgement.

Sadly for him, and sadly for public life, the political jury has already returned its verdict on Sir Geoffrey. He is, so far as can be seen, quite finished, and – setting aside the envy and the “optics” – it is a bit of a shame. He is the victim of his own success – the money – and perhaps of his lawyerly mindset: the one that tends to the view that, if something’s within the rules and it’s legal, it must be ok. That’s crude and unfair, because Sir Geoffrey is well aware of such dangers, but it’s how it looks that counts. Together, the money and the legal mind seem to have created blind spots, like the claim he once made for a 49p carton of milk, a £2 box of tea bags, and £4.99 for some weedkiller for the constituency office (though not for any sinister usage).

Had his judgment been better, and had he paid more attention to perceptions, you’d suppose that he’d be adding a bit more ballast to the top table (compared to his predecessor Jeremy Wright or his successor Suella Braverman), and exercising some sort of mild restraint on our wilful, impatient, legally careless prime minister. With his tubby, Rumpole-esque persona and his ready wit, Sir Geoffrey would generally add to the gaiety of the nation, but that prospect has now evaporated. He won’t, though, ever have to worry about where his next square meal is coming from.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments