Why Ellan Vannin is the British Isles’ best kept secret

This is the mysterious Celtic alterego of an island you know by another name, says Mark Jones. Whatever you call it, here’s why you should visit

Ellan Vannin is an island in the middle of the Irish Sea. It is often shrouded in mist, allegedly because its resident sea god, Manannan mac Lir, wants to protect it from unexpected visitors.

If so, he has largely succeeded.

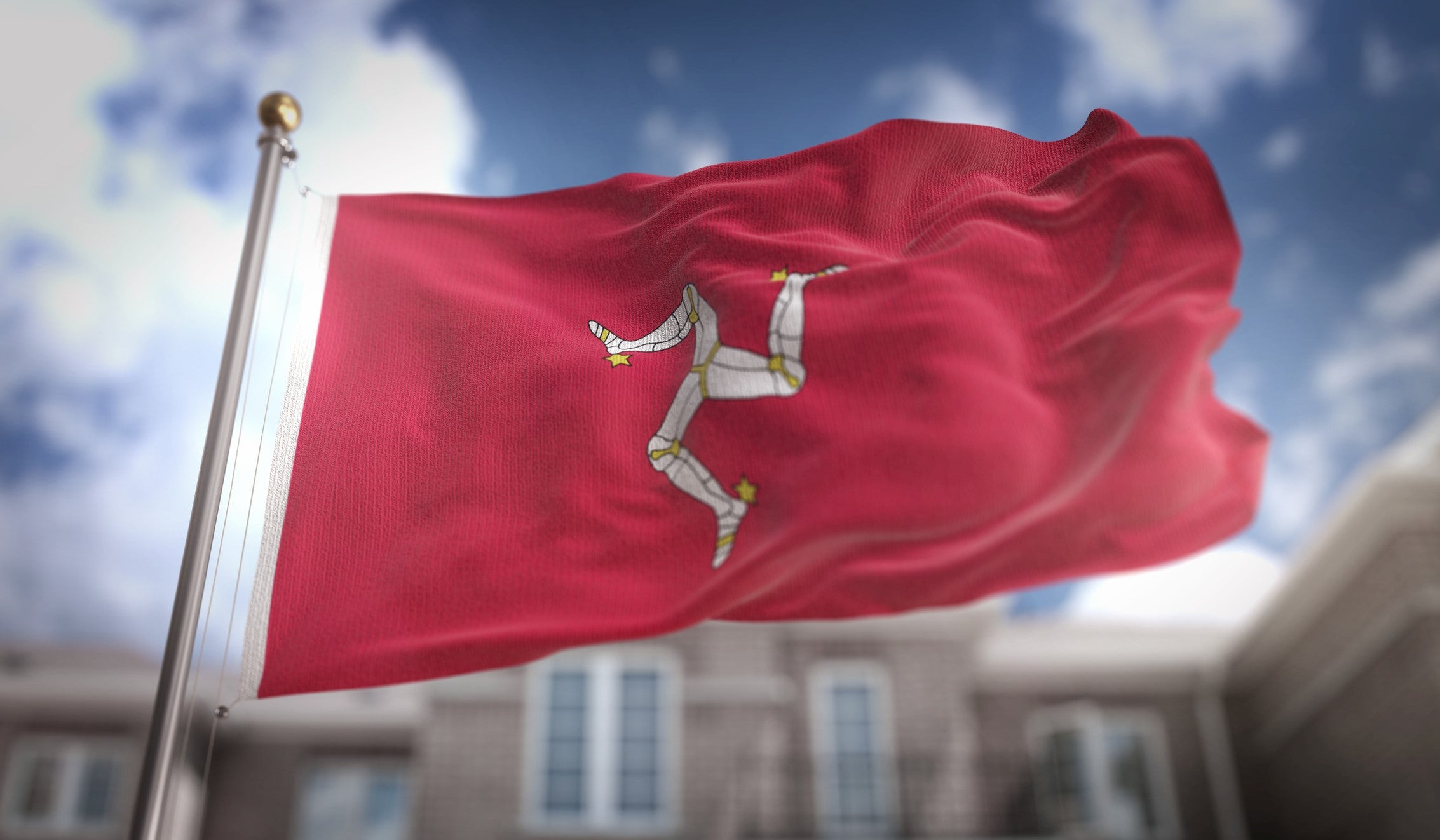

The island, which looks like a small rodent swimming in a northeasterly direction, is not part of the United Kingdom, nor the European Community. It’s a place of strange creatures – many-horned sheep, a bizarre feline sub-breed – and great natural beauty. Unesco named the whole island a protected biosphere for its geographical variety, clean beaches and remote hills.

Its villages and towns seem stuck in a Brigadoon timewarp, linked by steam railways and shaded country lanes. The native language is a Tolkienesque blend of ancient Celtic tongues.

Ellan Vannin – Insula Manavia to the Romans – has quietly been building a name for itself as a food and drink destination. Its scallops, cheese and – wait for it – kippers have an avid following among chefs. They have purity laws governing the local beer – and ice cream.

The people who come here – many get posted for work and settle – value the old-world neighbourliness, clean air and how easily you get around this 32 miles long by 14 mile-wide place, from the rocky shores of the south, the heathery plains of the north and the cheery port of the capital.

The island is only an hour’s flight from London and it’s connected to all the main British cities. So why doesn’t the mysterious isle of Ellan Vannin feature on more must-visit lists?

Possibly because it’s better known by its English name: the Isle of Man.

If travellers have a view of the IoM – and it’s hard to find many who do – they probably think of it as a tax-dodging chunk of Lancashire that found itself in the middle of the sea and is taken over by lunatic bike racers once a year.

The island’s tourism industry reached its height just before the First World War. The 663,000 who arrived on the steamships then had dwindled to 267,000 by 2018 – and 45,000 of those come for the annual Isle of Man TT motorbike race.

The remnants of that cheery Edwardian heyday are still there: a fine, cream-coloured seafront and a happy little electric train that coasts up the highest point of the island, Snaefell. From there, they tell you, you can see the seven kingdoms: Man, England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, the Ocean and Heaven.

They tell you this quite a lot. And about the fairy bridge; there’s one of those too.

The only kingdom I could see as my cab crept into the capital, Douglas, was a municipal domain of roadworks and shuttered shopfronts.

Things cheered up with a slug of albarino and the famed queenie scallops at the Tanroagan restaurant. But as I trudged back through the puddly, pedestrian-free pedestrianised street and roadworks (they’re relaying the seafront road), the mystical charms of Ellan Vannin seemed a long way off.

But a new day brought clear skies. And clear water – thanks to a big investment in, well, sewage management, and the sterling efforts of a one-man anti-rubbish operation called Beach Buddies, Man’s marine environment now complements its notoriously fresh air.

I went hiking with local archaeologist Andrew Foxon, who is very passionate about the Bronze Age. We pottered about King Orry’s Grave, a 5,000-year-old burial ground next to someone’s bungalow. Andrew was happy to come a bit more up to date and talk about the mines that profited from the zinc boom of the 19th century. The mines still reach for miles underground: on the top there’s Lady Isabella, a fairground-looking waterwheel.

Eschewing the chance to buy an Isle of Man tartan kilt at the very nice weaving shop, we had a coffee at the sunny beachside village of Laxey. Perhaps the name, a derivation from the Norse word for salmon, attracted the big fat seal that lay on the pebbly beach while we chewed our vegan flapjacks.

I played 18 holes of golf at the fabulous Castletown links, driving off towards the imposing King William’s College and scaring the local chuffs as my tee shots were caught by the wind and veered off into the bay.

It began to strike me that I was enjoying myself rather a lot. A couple of pre-dinner products from the Seven Kingdoms gin distillery and restaurant didn’t dampen the mood.

While a handful of artisan gin and beer operations doth not a hipster town make, Douglas is becoming a centre for e-gaming, online gambling and blockchain companies – so expect the beards to get longer and the bars livelier.

The next day brought a shock. The Victorian red-brick Douglas train station has been lovingly refurbished. But instead of hosting the usual performing arts centre or a co-working space, it turns out to be a place where you get tickets to go on trains. It’s all very Brief Encounter – the trains run (slowly) on steam power and inside my carriage the talk was largely about fuchsias.

At Castletown, I got off to look at the castle and have a pint. It was very relaxing in a 1953 kind of way. A tail-less Manx cat sauntered down the street pursued by American tourists with cameras.

Feeling that was all the action I was going to get in Castletown, I dropped in on the inventor John Taylor to experience his unique collection of clocks, fossils and opinions. He lives in a unique elliptical-min-castle overlooking sea and airport, which he designed himself. He designs everything himself. Throughout, there is a strange symbol on the carpets and balustrades. This turns out not to be a Celtic rune, but a gizmo he invented to turn kettles off automatically. You can do well from a patent like that. The house, Arragon Mooar, is on the market for £30m.

If you’d asked me before I went I’d have thought you could have picked up the whole island for around £30m. But this diverse, idiosyncratic place has what the estate agents call “fantastic potential for development”. If you ask me, the rebranding boys and girls should start with the name.

Travel essentials

Getting there

British Airways and easyJet fly from destinations across the UK to the Isle of Man from around £45 return.

Staying there

Mark Jones stayed at The Claremont Hotel, probably the best of the seafront hotels (but note: it can be noisy at the front thanks to roadworks). Rooms from £110.

Visiting there

For information on visiting the Isle of Man, go to visitisleofman.com

If you want to go further and look into working or living on the island, go to locate.im

For more information on the Castletown links course: castletowngolflinks.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments