A growing workforce, but is it becoming less efficient?

More than a decade after the global financial crash, the UK still has to face some difficult truths if it is to have any chance of a healthy economic future, writes Chris Blackhurst

The memory plays tricks. Looking back now, to the beginning of this decade just ending, it is easy to forget the extent of the crisis that had befallen us. Sure, we’re feeling the effects of ever-intensifying global pressure, and we’re uncertain about our future place in that world and how our relations with our EU neighbours will unfold. But honestly, they’re as nothing compared with 10 years ago. Then, we’d seen one of the world’s biggest, seemingly most powerful, banks literally collapse. Watching those employees leave Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008, carrying their belongings in cardboard boxes, it seemed as if we were heading for catastrophe.

That continued to be the dread for some time afterwards, as other banks here, in the US and across the globe, also plummeted. What began with some borrowers defaulting on their sub-prime loans turned into an almighty economic earthquake. “The financial crisis ... was followed by the deepest recession experienced in the UK, and much of the western world, since the Second World War,” wrote Jonathan Cribb and Paul Johnson in their analysis of the emergency for the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Something as profound as that comes at a price. Of course, employment would suffer, and GDP would falter. Normally, though, history suggests, the recession is short-lived and then we recover. Not this time. “What has proved most remarkable about the crisis and recession, though, was not its initial scale but the persistence of its effects. We had got used to the economy, and with it, the public finances and household incomes, bouncing back strong following previous downturns. That has not happened this time.”

It may be, of course, that this should have been expected of such a calamitous event. Nevertheless, the slowness of the recovery has caused surprise, and it is the overriding theme of this UK economic decade.

The nation’s income, as evidence by GDP, is up just 9.7 per cent since its pre-crisis peak, and is 12-13 per cent higher than the lowest point post the crisis What this means is that we’ve endured a long period of relative economic flatness. Perhaps the more telling measure is that the economy is much smaller than it was predicted to be before the crisis hit. Then, we were on a steep upward trajectory until, suddenly, we came crashing down.

This is why the post-crisis journey has been so unusually laborious – it’s because the economy in the run up to Lehman’s demise was artificially strong. It was a boom propelled by the City. In the UK, too much of our economic strength was dependent upon financial services. That sector grew in importance and clout, and it created a false impression of our overall economic strength. Manufacturing, for so long our bedrock, was shrinking, but that did not matter while the bankers and financiers were raking it in.

To understand what occurred in Britain these past 10 years it is necessary to cast your mind back further, to the years prior to Lehman’s explosion. It was a crazy period, one in which conspicuous consumption fuelled by City bonuses was a dominant theme. House prices, especially in London and the southeast, soared. Apartments (apartments!) changed hands for multi-millions; the capital appeared awash with foreign money searching for investment opportunity; nothing seemed too outrageously expensive.

There were those of us who shook our heads at the extravagance, the decadence, and wondered where it would end. We did not, however, predict the causes of the eruption, or its severity. Anyone who says they did, in precise terms, is being parsimonious with the actualite.

We knew it could not go on, but we had no idea: that mighty banks would tumble; the financial markets would suffer a severe wound; governments would have to use taxpayers’ cash to mount a lifeboat rescue operation; and that the consequences would include, alongside a dramatic tightening of belts, the imposition of stricter controls that would limit future investment and borrowing.

This past decade has been characterised by a slowing-down in deals – a result of tighter strictures on banks’ ability to lend, the requirement to maintain higher reserves and greater attention paid to compliance. Technically, at the moment we entered the new decade, in 2010, recession in the UK had been and gone. We’d endured two successive quarters of negative growth in 2009, the formal definition of recession, and that was that. By the end of the noughties and the advent of the next 10 years, from 2010, we’d been through the worst.

Except that is not how it ever felt. That’s because the recovery for the most part has flattered to deceive – it’s been long and steady, but slight. And the levels of growth have never reached the pre-crisis heady abandon, and given the dominance of the financial sector in that rush, and the subsequent imposition of emergency braking systems, they’re not likely to be in the immediate future, if at all.

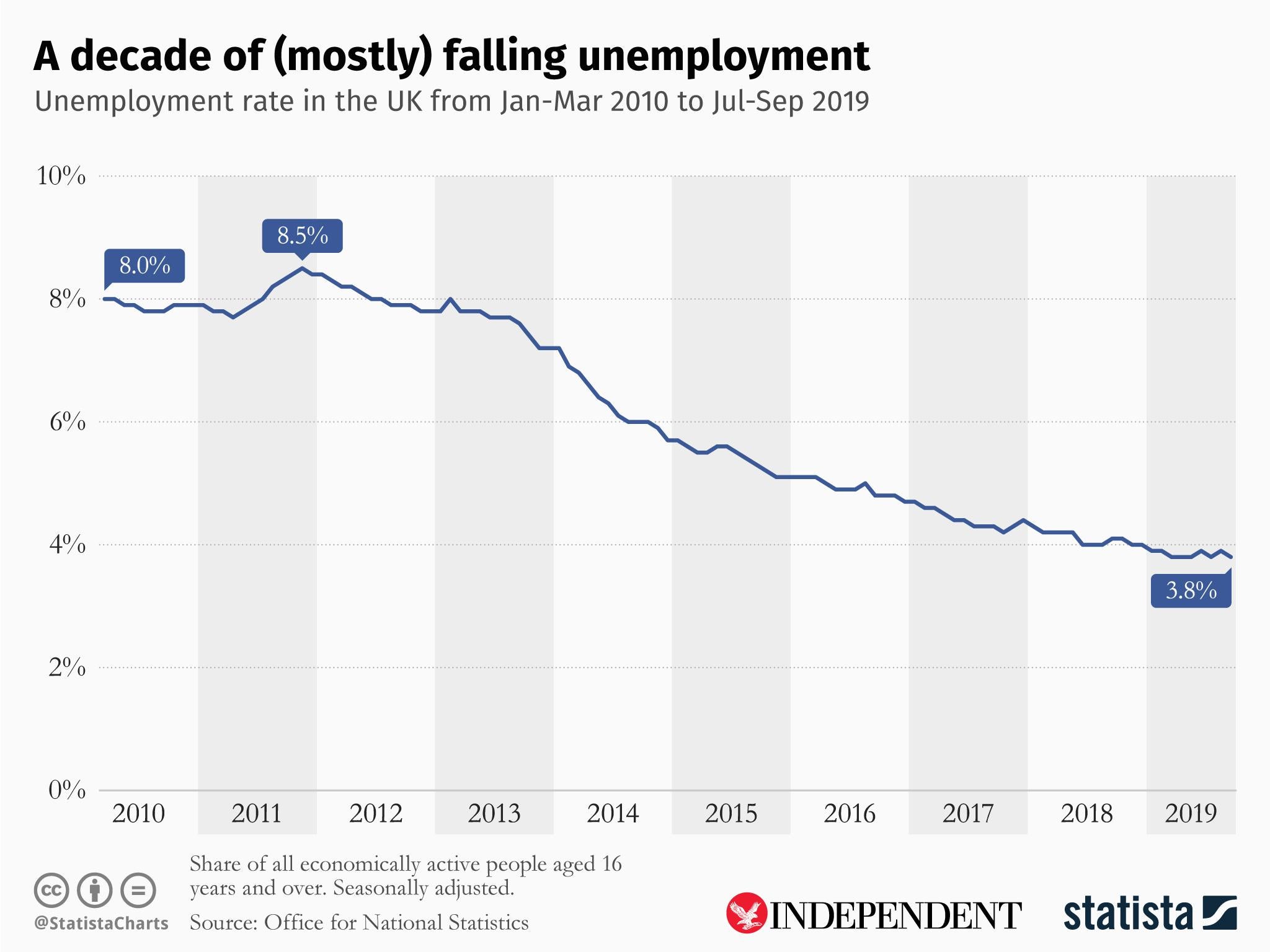

Yes, employment is up – to 32.5 million since we started the decade, from 29 million. Indeed, the creation of jobs and more jobs is our greatest economic success of the past 10 years. By 2015, David Cameron liked to say when he was prime minister, Britain had created more jobs post the financial crash than the rest of the EU put together. From 2015, the labour market has continued to improve. It’s enabled successive governments to proclaim that Britain’s economy is strong.

There were those of us who shook our heads at the extravagance, the decadence, and wondered where it would end

This, while austerity measures have been introduced, public services have been cut, and the welfare budget has been mangled. The experience of being in Britain this past decade has not been unlike one of living in a parallel universe. On the one hand, public facilities have closed or been cut back with consequent job losses and hardship; on the other, the number of those in work has risen.

The sense of division has been palpable. Between the public and private sectors; between those in employment and those without; between the young who struggle to get on the career ladder and must face the constant threat of AI and increased use of technology by would-be employers and older people who are living longer and more able to enjoy the fruits of their pensions; between the rest of the country and a London and the southeast that still enjoys the benefits of having international hegemony in finance and the new boom in fintech.

Remember also that the last portion has seen a draining in policy initiatives that often provide a financial stimulus in favour of arguments over Brexit. Remarkably, against this backdrop, as has been said, employment has held up well. More than that, it’s grown. And politicians have not been slow to boast about it.

But how many of those additional 3.5 million are genuine, full-time jobs? A glance round coffee bars in any city or town and the sight of all those people hunched over their laptops, will confirm a trend of the decade, the rise of the self-employed worker. The latest study from the Office for National Statistics found that freelancers totalled 4.9 million of the working population, or 15 per cent.

The experience of being in Britain this past decade has not been unlike one of living in a parallel universe

That jobs increase requires still further scrutiny. One of the oddities of the employment market is the availability of professional and senior jobs available, and unskilled jobs at the bottom, and not much in-between. The Institute for Employment Studies confirms this: of the newly created total of 3.4 million jobs when it conducted the study (now 3.5 million), 2.5 million were classified as professional or senior roles; 500,000 were low-skilled; and only 400,000 occupied the middle ground of skilled and semi-skilled.

By and large those top posts have gone to older workers working longer: they’re the ones equipped to occupy responsible managerial positions. Younger entrants to the employment market, by contrast, have struggled to fill them.

Meanwhile, the removal of age limits and the raising of the state retirement age have encouraged those who might previously have contemplated leaving to remain in employment. As well as holding on to senior jobs, many older workers are also dipping down, taking jobs in supermarkets and other industries that might once have been earmarked for younger employees.

Still, the labour market is up, and that is of enormous economic benefit – if not quite the triumph that is suggested by some eager political minds. Another, accompanying, factor has been the lack of wages growth in the past 10 years. Jobs up, unemployment down, pay, er, stagnant.

Britain has suffered a real wage squeeze, while more of us are finding employment. Repeated studies have found that the average worker is now worse off than they were a decade ago. Overall, said the Institute for Fiscal Studies, annual wages were £760 lower than a decade ago. More recently, wages have begun to outstrip inflation, but over the course of the decade this has not been the case, wages have remained flat. Indeed, once they’re adjusted for inflation, the average worker took seven years from 2010 to recover their pay to the pre-crash level.

Our employment rate may be the envy of other nations, but our workers are not working as efficiently. Governments have repeatedly failed to tackle it in a meaningful manner

Worryingly, people have been borrowing heavily again. Low interest rates have seen a rise in personal debt, to the extent that household debts have overtaken pre-crash heights – an era, let us not not forget, that witnessed the ready availability of mortgages for 100 per cent of value or more, and lending based on sometimes more than three-times salary and self-certification. That indebtedness has also been exacerbated by the rising cost of university tuition.

Jobs up, unemployment down, wages flat, borrowing up, and savings? They’re also down, put paid to by sustained low interest rates and wages falling behind the cost of living forcing people to dip into their savings pots and deposit accounts to make ends meet.

The most alarming aspect of Britain’s economy over the past decade, though, has been our inability to raise productivity. The dip started with the financial crash, and is probably that collapse’s most significant consequence. Until 2008, and the crisis, we had the highest output per hour worked than any country in Europe. Then the crash came, and our industry and its workers switched off, and they’ve stayed there.

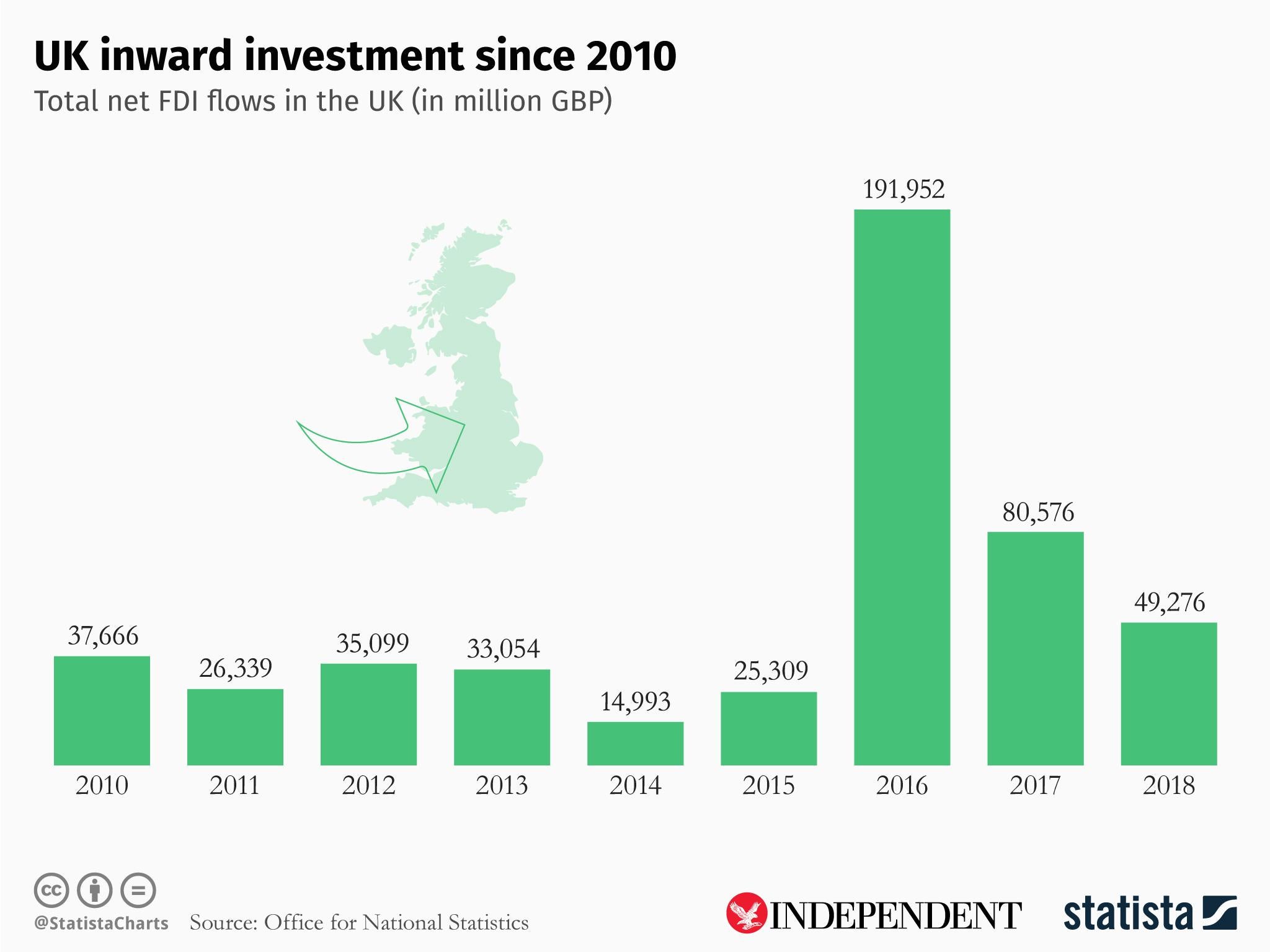

Our employment rate may be the envy of other nations, but our workers are not working as efficiently. Governments are all too aware of the problem – it’s not appeared overnight – but they have repeatedly failed to tackle it in a meaningful manner. As the new decade nears, as we examine our appeal to foreign investors with a myriad of destinations to choose for their money thanks to increased competition, we must make this a priority: why does £1 invested in Britain yield less output than elsewhere?

In a world of growing globalisation, where we can no longer take anything for granted, this is our weak spot – and it has been like this for the past 10 years. Some have even described it as “the decade of lost productivity”. Others would doubtless brand it as “the decade of austerity”, but while that is how it may have seemed, the name is wrong: austerity did not last a decade, did not touch everyone, while poor productivity has stayed the course, is a national disease, and must be resolved if the UK is to have a healthy economic future. The lack of investment in technology, in automation, and just as importantly, the skills required to get the most out of that new equipment, have to be corrected.

As does, too, the other main reason cited for our reduced motivation: employers do not treat their workers well enough, they do not devote enough resource to health and well-being, to ensuring, for example, they have proper childcare provision and are able to devote themselves to their jobs fully in the hours they’re required to work. It’s no coincidence that the most productive nations are those that invest in technology, and give their workers the skills to succeed, and look after them in the process.

Allied to our weak productivity is our national inability to push our small and medium-sized businesses on to the next level. Helping them grow, boosting enterprise, supplying the liquidity they require to expand – and not punishing them unduly if they fall short – has been a common complaint over the last decade.

Ten years from now, it would be wonderful to say these grievances have gone, and how much the economic landscape has improved for the better.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments