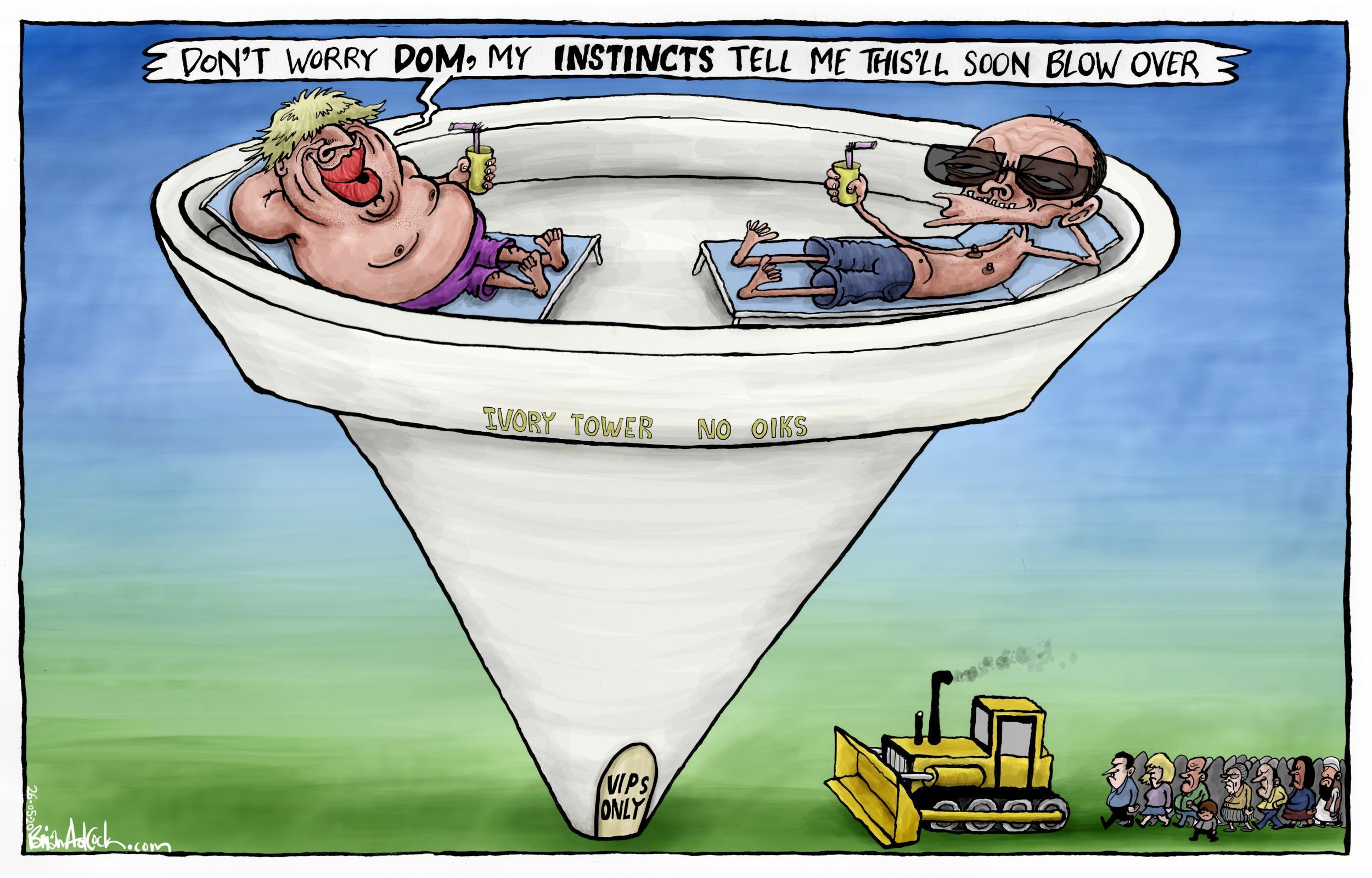

Out of the shadows and into the sunshine of the Downing Street rose garden, the British people got their first proper view of the (until very recently) obscure figure who has caused so much anger and consternation.

During Dominic Cummings’s long exposure to the journalists (who he is known to view with contempt), he did a number of things, not all of them helpful to the government’s case. First, he expressed no regret, no contrition and habitually blamed the media for the public’s widespread hostility. Second, he betrayed a certain amount of subterfuge when he said he’d not informed the prime minister about his movements straight away. Third, he admitted that he could and should have got his side of the story out earlier, and he nailed a few canards. Most of all, though, Mr Cummings confirmed that he had indeed broke the very lockdown rules he was partly responsible for, though he pleaded mitigating circumstances. The original point stands: he did not have to drive to Durham in the first place, and the rules did not allow for it. It remains an insult to the public. The story about testing his eyesight by driving through County Durham for 30 miles was a particularly tall tale.

By far the most important consequence of the Cummings scandal remains the damage it has done to the government’s still central message of staying home, still technically in force despite being already diluted to the nebulous “stay alert” slogan. It has given a green light to those tiring of social distancing in any case.

Adding the “Cummings effect” to the tentative moves on shops, open markets and car showrooms announced by the prime minister will inevitably mean more social contacts. That, in turn, suggests we may expect some increase in the incidence of infection and if the R rate, the reproduction rate, representing the speed at which any given number of cases will grow. The obvious risk is that it may rise above one in some parts of the country where it is already comparatively high. As it happens, this includes the north east of England; there and in some other places a second wave of hospital admissions will stretch still-inadequate NHS resources.

The impression given by the government, apart from a fairly counterproductive attempt to regain control of the news agenda, is of it attempting to fine tune its exit strategy. Ministers do not want to be so cautious that they risk permanent damage to the economy; but neither do they wish to see the NHS overwhelmed.

To be fair to the prime minister, his fresh announcements about easing restrictions are modest, but they do add to the risks, as does the partial re-opening of nurseries and schools.

Only four cohorts of schoolchildren will be invited to return to the classroom over the next few weeks, and there seems no appetite to impose punitive sanctions on parents, teachers or local authorities who feel the time is not yet right. Safety of all concerned – which encompasses older relatives and the wider community – should still come first. The precise arrangements for social-distancing and use of protective equipment are still to be worked through. Not enough is known about the way the coronavirus affects children for anyone to rule out risks to public health, but there is growing international evidence that they are at lower risk of serious harm, and may be less infectious.

For any relaxation to be fully safe, however, much more needs to be done to inspire confidence in the test and trace regime before more of the exit strategy is launched. Test-and-trace, as lockdown winds down, will become the nation’s first line of defence against Covid-19. Plainly, the system is not yet ready. The app doesn’t work, the number of tests is still too low and below the prime minister’s goal of 200,000 per day, the testing personnel are mostly inexperienced, and there seems to be confusion about who is running the system – local councils, public health agencies, devolved and national governments or the NHS?

The government was right to set out as its fifth principle on moving lockdown through its colour coded stages from red (stringent lockdown) to green (eradication of covid) that there should be no risk of a second wave that would break the NHS. Ministers need to be more conscious of the force of that criteria as anyone else. Quite apart from anything else the political fall out for this government, so complacent, so incompetent and so arrogant, from a Lombardy-style medical emergency would be terminal. By then the future career of Mr Cummings will be pretty irrelevant.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments