Disco Demolition Night: How racism and homophobia nearly burnt the genre to the ground

It’s been 40 years since Chicago’s Comiskey Park hosted a cultural bonfire – reminiscent of Thirties Germany – attended by an overwhelmingly white crowd. But the phoenix of disco rose from the ashes, writes Jake Cudsi

It was a disco inferno; and no, not that one. Three years after The Trammps released their 1976 album, disco records were set ablaze in a cultural bonfire reminiscent of 1930s Germany.

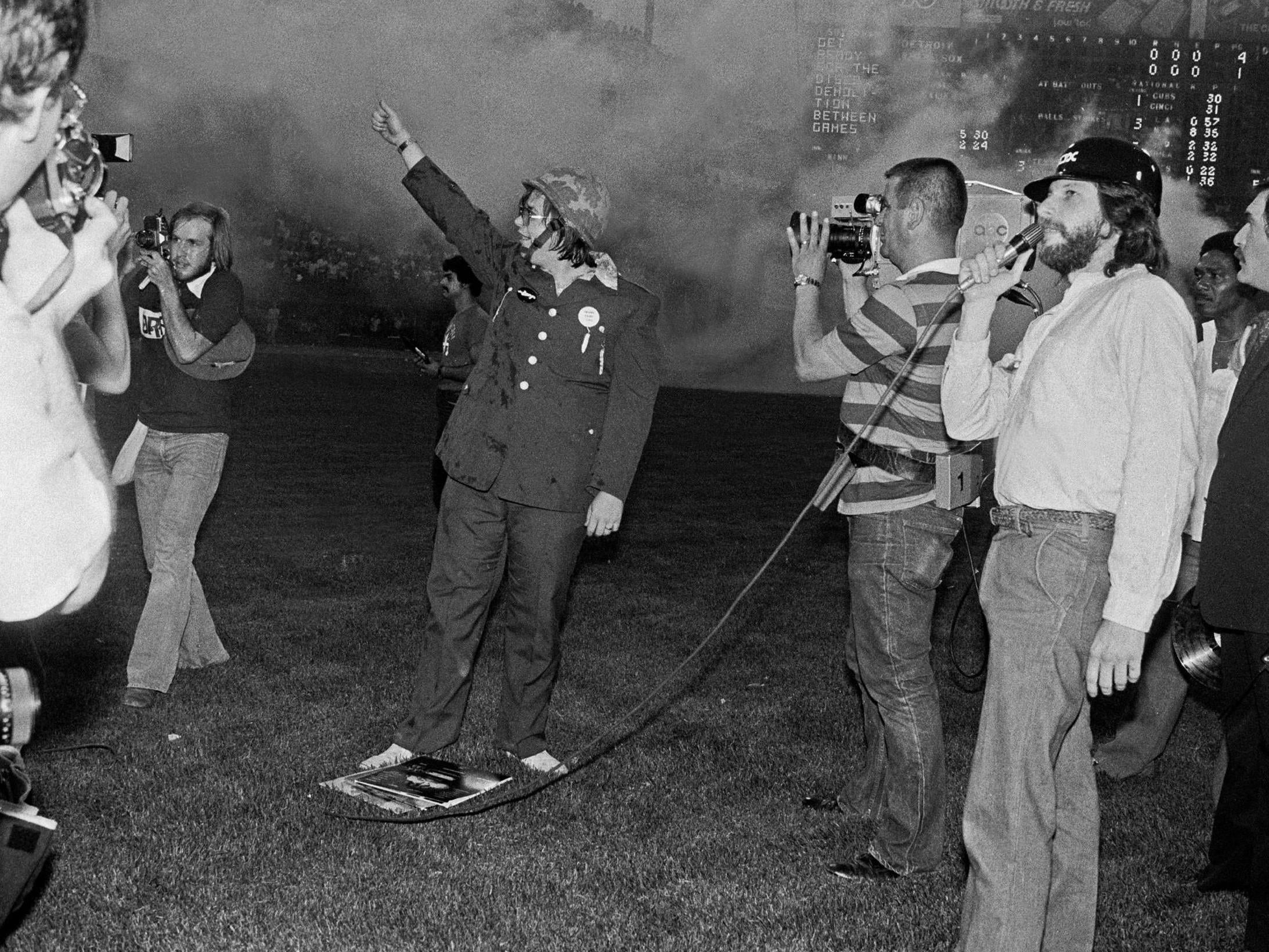

On a hazy July evening in 1979, an overwhelmingly white crowd packed out the Chicago White Sox’s Comiskey Park to attend Disco Demolition Night. Almost 60,000 fans turned up with records, ready to be burnt, detonated and smashed.

The event was a fever dream, thought up by an aggrieved DJ on the Chicago radio station WLUP. In early 1979, Steve Dahl found himself out of a job, defenestrated, he insisted, by WDAI after they switched to a more disco-oriented sound.

On his new show at WLUP, Dahl would regularly destroy disco records on-air. It struck a chord with listeners and Dahl was soon printing bumper stickers and hawking merch attacking disco. The Disco Sucks! campaign was born. Things moved fast, just as they had done for the disco scene itself.

In the 1970s, disco’s ascent was extraordinary. Influenced heavily by the Motown sound, the genre was the hallmark sound of the underground club scene. Created by black and latino musicians, the music was particularly popular among the black, latinx and LGBT+ communities.

Two moments helped launch disco’s immediate catapulting into the mainstream, and help ensure its enduring legacy. The first was the 1977 release of Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love”. The almost space-age production and entrancing vocals would prove instructive for later dance music.

Then, to repackage the sound to a wider, whiter audience, the Bee Gees-soundtracked Saturday Night Fever was released in cinemas. The soundtrack remains one of the best-selling albums of all time, and topped the album charts in the US for 24 consecutive weeks. Disco had become the pervading pop sound.

Dahl decided to act. According to the author and journalist Ben Myers, the disgruntled DJ struck a deal with the Chicago White Sox owner Bill Veeck to host his demolition night. The deal came about because Veeck’s son Mike, a failed rocker, was heavily involved in Dahl’s anti-disco cause.

A date was set, and fans were invited to bring records to explode during the interval of a baseball double-header between the White Sox and the Detroit Tigers. People with a disco record to hand got a generous discount on their ticket.

The disco inferno pointed to a wider prejudice possessed by the Disco Sucks! crowd. Vince Lawrence, an usher at Comiskey Park, that night noticed the destruction of music wasn’t just limited to just disco. Black artists of all genres were being thrown into the pile.

After the first game, Dahl blew up thousands of records rigged to dynamite. The second game was called off. The crumpled vinyl smouldered, a burning effigy of an alien culture, in a scene the Rolling Stone critic Dave Marsh described at the time as the “most paranoid fantasy about where the ethnic cleansing of the rock radio could ultimately lead”.

But what may have started as a paranoid fantasy soon became a vision shared by many across the nation. The Comiskey Park publicity stunt shot Dahl to fame, strengthening his movement. In Dave Hoekstra’s book Disco Demolition: The Night Disco Died, legendary Chic guitarist recounts the mood in the event’s immediate aftermath: “The ‘disco sucks’ thing became very real. It was scary.”

That fear was keenly felt by labels, who became more and more unwilling to produce disco records. Within months of the demolition night, disco was near-absent from the airwaves and abandoned by the charts.

The anti-disco even garnered the support of politician JB Bennett, who ran for state senate in Oklahoma vowing to end disco’s “corrupting influence on our young citizens”.

Opposition to disco was also viewed as a rejection of “gay music”. The backlash was as much about the “look” and “culture” as it was the music, as Dahl himself so often confesses. He has, tellingly, called disco “an intimidating lifestyle… forced down our throats”.

The Chicago Reader’s Tal Rosenberg remembers the anti-disco movement as a “dumb display of prejudicial anger”. While the record producer Simon Napier-Bell went further, telling Timeline that Disco Sucks! was “anti-everything that didn’t subscribe to the right-wing rednecks’ idea of what America should be”.

With disco in decline, disco clubs rapidly dissipating and America moving into a new, conservative era under Ronald Reagan, the genre had surely had its day. Or had it?

From the ashes of that dark night in July, the phoenix of disco transcended radio’s airwaves, its seminal influence birthing impactful, influential new genres which continue to dominate popular culture.

And elsewhere in Chicago, another crowd was hard at work. Or is that play? Chicago had staged disco’s darkest night, but it was also the scene of a new dawn. Named after Warehouse, the Chicago club which proselytised the new sound, house music exploded onto the city’s underground club scene.

One of disco’s many children, early Chicago house music leant heavily into the synthetic, mesmerising sound popularised by Donna Summer back in 1977. Beyond musical spirit, it shared the emotive, forward-thinking and loving philosophy of early disco.

House and dance music’s success has outlasted that of the original disco, as has hip-hop’s, another genre taking inspiration (and more than a few samples) from the disco sound. Modern pop music is mantled with its influence.

As we enter the fifth decade of post-disco demolition night, their sustained time in the sun is a legacy, in no small part, of the enduring allure of disco music and culture, which ultimately survived that bonfire night of hate in ‘79.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments