Cleo from 5 to 7 secures Agnes Varda’s place at the heart of the French New Wave

In a different, less oppressively patriarchal world, Clarisse Loughrey writes, film students would be as familiar with the film as ‘Breathless’ or ‘The 400 Blows’

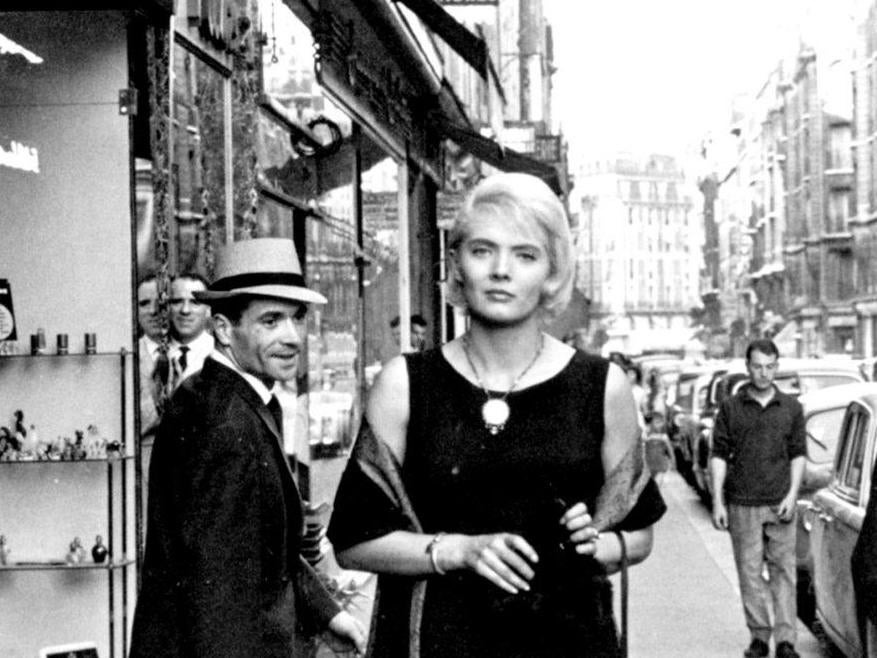

Cleo from 5 to 7, Agnes Varda’s spirited French New Wave classic, imagines Paris as a house of mirrors. One always ends up faced with their own reflection – in shop windows, tiled cafe walls, or hat shop looking-glasses. Strangers exchange glances, only to see themselves imaged in each other’s curious expressions. A young woman wanders the city, contemplating her own mortality. We look at her. She gazes at herself in the mirror. Her reflection looks back at us. Others notice her presence, but rarely see her as she is. Beauty has made her body visible, but not her soul.

Varda has long been called the grandmother of the French New Wave. But the title is insufficient – she was its heart, since she understood best the power of a camera’s gaze. While her male compatriots (and they were almost all male) were often critics and academics, she arrived on the scene a photographer. Cleo from 5 to 7 is not only exquisitely composed, but understands intimately the art of looking – how women, specifically, are created and destroyed in the eyes of others.

Much of the modern narrative around Varda has focused on her relative marginalisation in the annals of history. There’s no doubt that in a different, less oppressively patriarchal world, film students would be as familiar with Cleo from 5 to 7 than they would be Breathless or The 400 Blows. Only in the last decade has her place at the centre of the New Wave movement been formally recognised – in 2017, she won the honourary Oscar, two years before her death.

The film follows Cleo (Corinne Marchand) in real-time from 5pm to 6.30pm – the missing minutes later become significant – on 21 June 1961. She’s a singer on the cusp of renown, awaiting the results of a medical test she fears will confirm she has stomach cancer. Cleo seeks out the others in her life, in the hope they’ll bring her some small comfort. As she walks through the city, people crane their necks to catch a glimpse of her beauty. She sees her assistant and buys herself an expensive, but unseasonal winter hat. At home, she’s visited by a lover (Jose Luis de Vilallonga) and two songwriters (Michel Legrand, who wrote the film’s score, and Serge Korber). Later, she meets a friend who’s a life model (Dorothee Blanck).

None of them take her plight seriously. A porcelain songbird like Cleo could never be marked by injury or death. To them, she’s a plaything – a guise she’s welcomed as long as it placed her on a pedestal. “Everyone spoils me, but no one loves me,” she bemoans. When a meeting with a fortune teller (the film’s only colour sequence, rendered in burnt shades) goes awry, she runs to her reflection in the mirror. “Ugliness is a kind of death,” Cleo tells herself. “As long as I am beautiful, I’m even more alive than the others.”

But morality’s rude intervention has begun to distort her perspective, both literally – as she catches herself in the shards of a shattered pocket mirror – and spiritually. She’s now left to the will of the universe, uncovering signs and superstitions at every turn. Carved masks and street magicians turn sinister. The silent film her friend shows her (in which New Wave titans Jean-Luc Godard and Anna Karina cameo) has a meaning that seems to elude her. Marchand’s slinky, feline nature – accentuated by a flick of black eyeliner – turns skittish. Her back arches in defence. Varda, with her documentarian’s eyes, captures both the small shifts in Cleo’s behaviour and the cacophonic, electric city behind her.

While alone in the park, she’s approached by Antoine (Antoine Bourseiller), a soldier on leave from the Algerian War. He offers to accompany Cleo to the hospital, where she can confront the doctor instead of nervously waiting for his call. For the young man, the war has rendered death empty and meaningless. Their proximity to it brings them close. Antoine is courteous and attentive, too. He listens. He understands. Their time together is idyllic. For the first time in Varda’s film, someone has seen past surface illusions. Cleo is finally of flesh and blood – not a trinket, nor a passing flirtation. She no longer seeks solace in her reflection.

Varda, ever-mischevious, offers us a final twist. Cleo’s doctor reveals that her illness isn’t terminal – a few months treatment will cure her. She and Antoine walk away, side-by-side. She tells him she’s happy. But why, then, does such an uncomfortable silence descend between them? Is it because they’re no longer lovers on borrowed time? Varda lets her audience choose what Cleo did between 6.30pm and 7pm. Her gaze has turned on us.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments