Surrealism Beyond Borders review: Presents the art phenomenon as an inclusive, empowering life-force

This major Tate exhibition darts through works with a mind-boggling array of approaches, and of immensely varied quality – but it is put together with style and curatorial nous

Surrealism is one art phenomenon that everybody feels they understand. It may have been one of the 20th century’s truly momentous cultural movements, with its aspirations to undermine the entire social and political order by delving into the darker realms of the unconscious, and to explore the limitless visual potential of the language of dreams.

Our conception of Surrealism today, though, boils down to the rackety interwar exploits of a bunch of charismatic Paris-based bad boys – Dali, Magritte, Ernest, Miro et al – and a few of their key images. So if you get, say, Dali’s Lobster Telephone (a telephone with a lobster for a handle) and Magritte’s Time Transfixed (a meticulously painted train hurtling out of a fireplace), you basically get Surrealism. Right? Absolutely wrong, according to this major Tate exhibition.

Surrealism, it argues, was a far more diverse phenomenon than we’ve ever imagined, involving far more women and people of colour, and with critical nodes of activity from Brazil to Tokyo to Mexico City to Baghdad and beyond.

This isn’t the first time a Tate exhibition has attempted to open up and redefine a classic Modern Art moment. The World Goes Pop attempted something very similar in 2015, drawing artists from Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Latin America into the charmed circle of an art movement previously considered synonymous with New York and London, but without seriously denting our cherished perceptions of what Pop Art was about.

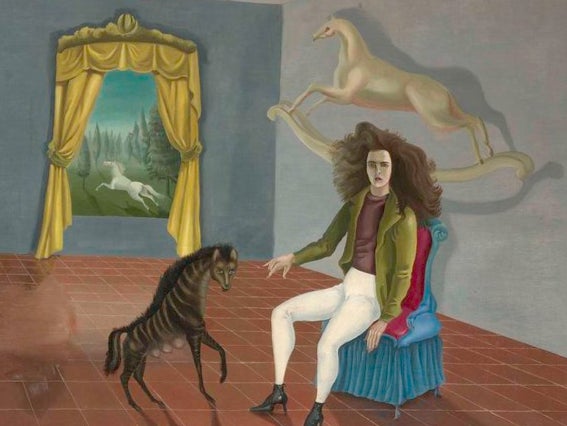

Taking on a vast morass of surrealistic endeavours, including artists who were barely aware they were surrealists and – weirdly – artists who rejected Surrealism outright, while expanding the movement’s time-frame right up to the late Seventies, Surrealism Beyond Borders has all the makings of an indigestible mash-up. And it’s one, judging by its poster image – English Surrealist Leonora Carrington’s twee Self-Portrait – that will be trying to browbeat, no, emotionally blackmail us, into elevating some very slight works into “iconic” masterpieces.

So much for the note of reasonable caution. While the show certainly darts through works with a mind-boggling array of approaches, and of immensely varied quality, it’s put together with such style and curatorial nous, I was entranced practically from the first room.

French painter Marcel Jean’s Surrealist Wardrobe (1941) sets the agenda with its six life-size cupboard doors appearing to fly open to reveal glimpses of dream-like, sun-lit landscapes. Cooped up in a Budapest flat during the Second World War, Jean found in Surrealism vistas of a yearned-for freedom. It’s a moment of discovery that re-echoes throughout the exhibition as artists from Havana to Tokyo via East Sussex (the show doesn’t rule out European or American art) find in Surrealism a means to achieving psychic, social and political liberation and transformation.

While there are a fair few well-known works from those Parisian bad boys, including – surprise, surprise – the lobster telephone and train coming out of the fireplace, they’re presented not as the great font from which everything else springs, but as just more and different manifestations of this most fertile current in 20th century art and thought.

In a room on The Uncanny in the Everyday, British artist Eileen Agar’s Angel of Anarchy (1936-40), a plaster cast head wrapped in silk fabric with feathers, sea-shells and beads – a work fast becoming the ultimate icon of “feminist surrealism” – stands near a quirky assemblage of household objects looking like a promising GCSE art project, which turns out to be Picasso’s Composition with Glove (1930). The adjacent wall is filled with photography by mostly little-known artists from Portugal, Korea, Chile and Mexico. While familiar Surrealist tropes recur – assemblages of mannequins, hooded figures, suggestively shaped rocks – these works still feel fresh and vital despite being in some cases approaching a century old.

Baton Blows (1929), Egyptian painter Mayo’s mass of ambiguous limb-like fragments suspended in space, with its strange undertow of violence, and Untitled (1967), a rich and dripping mass of eyes, teeth and blood by the Mozambican cattle-herder turned painter Malangatana Ngwenya, hang beside works by Miro and Max Ernst and more than stand their ground. That paintings covering such vast distances of time, space and style can be accommodated even in the same room is a testament to the deftness with which the show weaves wildly diverse works into a single stream of consciousness. It’s one that not only touches on the dream-like at all points, but, with its deep blue backgrounds, often feels like a dream experience in its own right. While the connections between works are of course “explained” in the wall texts, if you’ve got the slightest feel for Surrealism, it all essentially explains itself.

Film is particularly brilliantly used, not as an adjunct to the paintings, but as immersive wall-filling installations in the case of Tusalava, New Zealander Len Lye’s visionary 1929 animation inspired by South Sea Island totemic imagery and Maya Deren’s hallucinatory At Land (1944) in which the American feminist filmmaker crawls around a beach encountering alternative versions of herself. The inclusion of a section from William Klein’s extraordinary documentary on the 1969 Pan-African Festival in Algiers is justified by the appearance of African-American surrealist poet Ted Joans, though the sight of free jazzman Archie Shepp jamming with a bunch of blue-veiled Touareg musicians fits perfectly with the show’s expanded conception of surrealism.

Not everything is absolutely great. Indeed, by any conventional yardstick there’s more bad painting than I’ve seen in just about any other major exhibition, from Rita Kernn-Larsen’s patently amateurish Phantoms (1943) to Leoner Fini’s mawkish Little Hermit Sphinx (1948), and culminating in the teeth-grating whimsy of Mexican painter Remedios Varo’s autobiographical “fairytale” triptych with its posse of identical, sweetly smiling blonde girls – presumably resembling the painter – “weaving the mantle of the earth” in an alchemist’s tower.

But then Surrealism was never really about producing “good art”. It’s in the nature of the movement that you have to get past a few bits of hokiness to access magnificently bizarre stuff like Italian painter Enrico Baj’s Bodysnatcher in Switzerland (1959), with its monstrous blobby humanoid figure plonked in a kitsch alpine landscape (inspired by the 1956 horror film Invasion of the Body Snatchers), or Japanese artist Koga Harue’s plain weird attempt at “scientific Surrealism” – The Sea (1929) – with its blank-faced female swimmer and technically exact renderings of a submarine and industrial buildings.

There isn’t so much of the dark, disturbing side of Surrealism here – no breast slicing or eye gouging – still less of the slightly snooty, weirder-than-thou exclusiveness of the movement’s classic Parisian incarnation. It’s the sense of Surrealism as an inclusive, empowering life-force that anyone can access that makes this marvellous assortment of the startlingly brilliant, the beyond eccentric and the almost dreadful feel still fresh and strangely relevant to now.

Surrealism Beyond Borders is at Tate Modern Until 29 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments