Betrayal, sexual jealousy, sudden violence: Why directors are so transfixed by film noir

Steven Soderbergh’s ‘No Sudden Move’, a tribute to mid-century gangster thrillers, has just premiered at the Tribeca Festival. Geoffrey Macnab explores why directors continue to turn back to film noir

There is something about 1950s film noir that seems to transfix contemporary directors. In features ranging from Curtis Hanson’s James Ellroy adaptation LA Confidential (1997) to Steven Soderbergh’s new crime thriller No Sudden Move, this is the decade that filmmakers keep on revisiting. Everything about the Fifties intrigues them: the Cadillacs, the nightclubs, the factories, the race tracks, the boxing rings, the fedoras worn by detectives and criminals alike, the jazz music and the sad-eyed club singers. They are endlessly fascinated by the contrast between leafy, suburban family America and the goings-on in those shadowy, crime-infested alleyways downtown.

Soderbergh’s new film is set in Detroit in 1954. It has a classic heist narrative. Small-time criminals Don Cheadle, Kieran Culkin and Benicio del Toro are hired to steal a document. It’s a straightforward job, a few hours of work for a decent pay-off. They’re supposed to intimidate an accountant by invading his home and holding his wife and kids hostage. He’ll then go and get the document from his boss’s safe. “When their plan goes horribly wrong, their search for who hired them – and for what ultimate purpose – weaves them through all echelons of the race-torn, rapidly changing city,” reads the official synopsis.

This isn’t the first time Soderbergh has turned to film noir for inspiration. His 1995 feature The Underneath was a remake of Robert Siodmak’s crime thriller Criss Cross (1949). Several of his other films, including Out of Sight and The Limey, have included film noir elements. But No Sudden Move is actually set in the Fifties.

The term “film noir” was coined by French critics after the Second World War. As Martin Scorsese notes in his documentary, A Personal Journey Through American Movies, it was never a specific genre like the gangster picture, but “rather a mood which was best described by this line from Edgar G Ulmer’s Detour: ‘Whichever way you turn, fate sticks out its foot to trip you.’”

Inevitably, protagonists in these films get in over their heads. They’re fighting forces far greater than themselves. It’s often as if they are cursed.

The films don’t necessarily hinge on heists or organised crime. They can just as well be about infidelity or sexual jealousy. Cheating wives and their lovers conspire to kill off husbands for insurance pay-offs, or henpecked men murder the women who’ve been humiliating them. The pictures can be set both in sun-drenched California and in rain-swept New York, in big cities or provincial backwaters.

German director Fritz Lang’s Hollywood-made films of the genre invariably showed both the bright side of the American dream and its dark underbelly. Early on in his movie The Big Heat (1953), Lang goes to great lengths to depict the happy, all-American family life enjoyed by Sergeant Dave Bannion (Glenn Ford), his wife Katie (Jocelyn Brando) and his young daughter. They’re like the families you see in the commercials of the period. Then, Katie is blown up by a car bomb intended for her husband. The easy-going Bannion turns immediately into an embittered and ruthless man who will do anything to avenge her death. This is one of Lang’s most familiar and pessimistic themes: that seemingly civilised and selfless people can turn violent very quickly.

The Big Heat also includes the notorious scene in which the gangster thug Lee Marvin throws scalding coffee into Gloria Grahame’s face. “I don’t think that people believe in the devil with the horns and the fork tail, and therefore they don’t believe in punishment after they are dead. So my question was what are people fearing – and that is physical pain – and physical pain comes from violence,” Lang later explained, on the question of why he included such scenes in his work.

Such shocking violence runs through much of the film noir of the period: in Joseph H Lewis’s The Big Combo (1956), the dapper gangster kingpin Mr Brown (Richard Conte) tortures the cop hero Lt Diamond (Cornel Wilde), first by deafening him with jazz music and then by pouring a whole bottle of hair tonic (“40 per cent proof”) down his throat.

There is a whiff of misogyny that persists in many of the remakes and homages to the Forties and Fifties films. Many are told from the perspective of male protagonists who’ve been spurned by their lovers. When an insurance salesman like Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) ends up on death row in Billy Wilder’s adaptation of James M Cain’s Double Indemnity (1944), the femme fatale is bound to be held responsible. “I’m rotten to the heart,” Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson famously tells her lover, Neff. She is presented as the temptress who has ruined his life. He doesn’t pause to think that he may have ruined her life, too. “I loved you, Walter, and I hated him,” she says of her murdered husband. “But I wasn’t going to do anything about it, not until I met you.”

There is a similar dynamic in Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), also based on a James Cain story, in which the young wife (Lana Turner) persuades the drifter (John Garfield) with whom she is having an affair to try to murder her husband. “Cheap”, “uncertain” and “temptatious” were some of the adjectives used by contemporary critics to describe Turner’s character. These critics tended to be far more sympathetic to Garfield as the one who fell under her spell.

Both films were remade 30 years later, at the start of the video era, with the female protagonists still portrayed as negatively as they had been in the 1940s. Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat (1981) moved the Double Indemnity story from LA to a sweltering Florida. This time, William Hurt was the struggling white-collar worker who began an affair with a femme fatale (Kathleen Turner) and was quickly roped into helping her kill her husband.

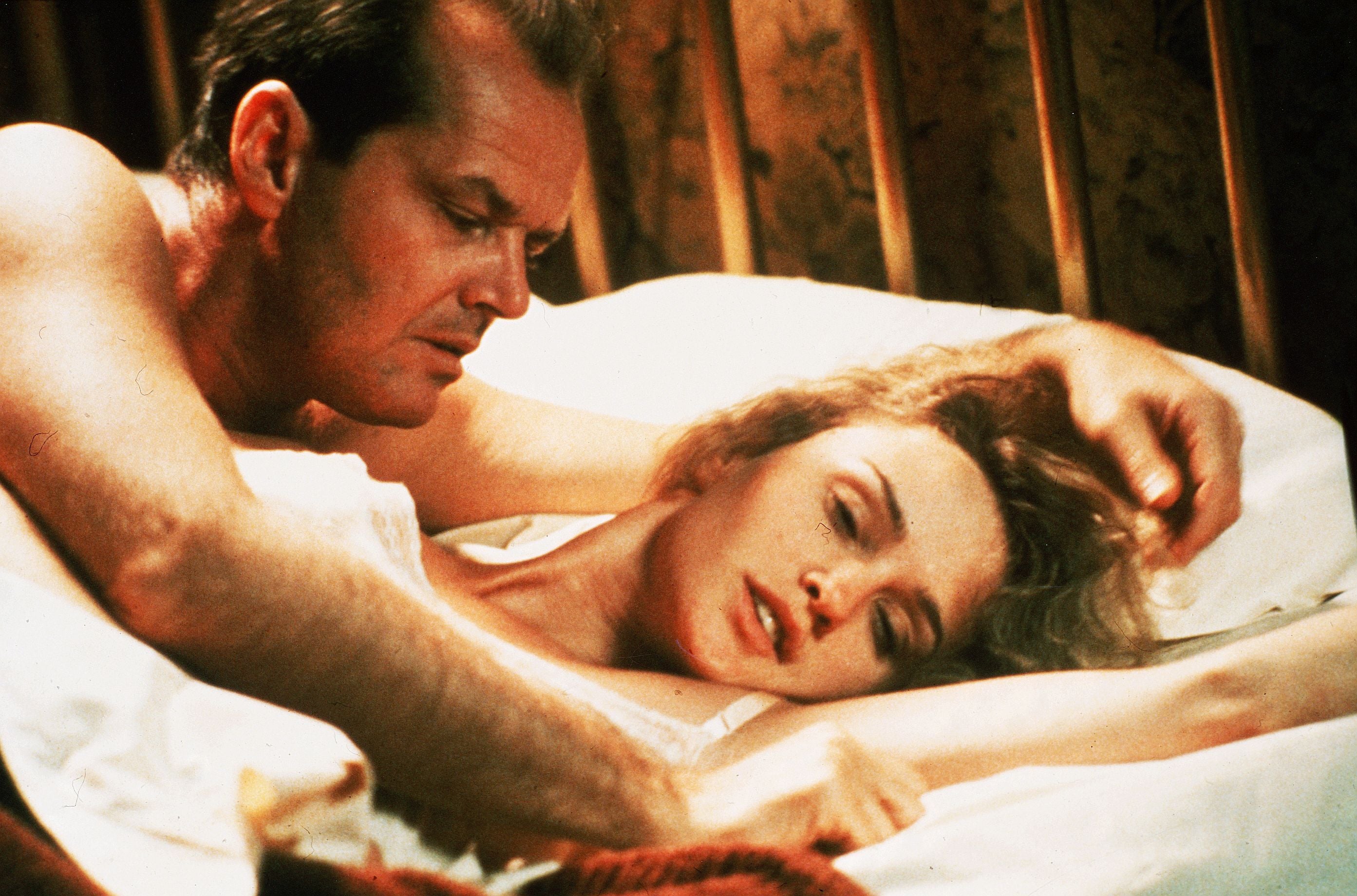

Meanwhile, Jessica Lange was the blonde temptress manipulating Jack Nicholson’s thief in Bob Rafelson’s steamy 1981 remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice. This was famous for the scene in which the couple fight and then have aggressive sex on the flour-covered kitchen table where Lange has been baking bread. (She throws away the bread knife rather than plunge it into his back.)

The scene hinted at the direction film noir was taking in the 1980s and 1990s. Directors were drawing on it as inspiration for souped-up erotic thrillers. Richard Marquand’s Jagged Edge,Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct,Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction and John Dahl’s The Last Seduction all owed an obvious debt to the films of the 1940s and 1950s, but now the storytelling was becoming more graphic and exploitative.

One of the fascinations of the original film noir had always been its mix of gritty realism and formal stylisation, what Scorsese described as “real locations and elaborate shadow plays”. From Ulmer’s pared-down Detour (shot in less than a week) to Lang’s The Big Heat (shot in under a month), these were films that were generally made quickly and on relatively modest budgets. However, the best of them have ingenious staging and photography. For example, in The Big Combo, cinematographer John Alton makes a modern American city seem as spooky and doom-laden as any godforsaken corner of Transylvania seen in an expressionist vampire picture.

The classics from the period remain in circulation. Titles like DOA, He Walked By Night, In a Lonely Place, The Hitchhiker, The Killers, Out of the Past, Cause for Alarm and many others are available to watch online, often in restored versions. Nonetheless, part of their continuing attraction is that they’re still not mainstream. One or two, notably John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle and Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing, are very well known, but most remain cult movies.

Often, contemporary audiences watching remakes or homages to old film noir will not even be aware of the original films that inspired them.

Steven Soderbergh is regarded as one of the most innovative figures in US cinema, always looking to disrupt and reinvent traditional storytelling and distribution models. It is telling, though, that he so often turns back to classic Forties and Fifties crime thrillers for inspiration. The enthusiastic response to No Sudden Move at its premiere last week suggests that many share his nostalgia. Other major filmmakers, such as Scorsese, David Lynch and Kathryn Bigelow, likewise continually draw inspiration from thrillers of the same era. For anyone else today looking to tell hard-edged stories about corruption, betrayal, sexual jealousy and sudden violence, film noir is still the place to plunder ideas from first.

‘No Sudden Move’ was premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and will be released in the US by HBO Max next month

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments