Why it’s a pity Putin doesn’t pay more attention to Russian cinema history

As his troops batter Ukrainian cities, Putin appears to have forgotten the message of reconciliation hidden beneath all the bloodshed in ‘Stalingrad’, the hit 2013 film that follows in a long line of Russian movies celebrating the heroism and fortitude of the Russian people under siege, says Geoffrey Macnab

A huge city is on fire. Foreign invaders are indiscriminately laying waste to its buildings. There is rubble everywhere. Department stores, factories, streets, and even individual apartments have become battlegrounds. Fedor Bondarchuk’s Stalingrad (2013) tells the story of the Russians’ heroic defence of the besieged city of Stalingrad in 1942, in the face of a Nazi army that targets the civilian population.

The film, shown in 3D IMAX and made with government support, was a huge hit in Russia. It tapped into what its director called “sacred territory for Russia”, namely the hallowed memory of the Second World War, the sacrifices made at Stalingrad, where close to two million people are estimated to have died in the battle for the city, and how the invaders were eventually repelled.

The film has a voiceover from a man in contemporary times whose mother survived the “inferno” of the city under enemy siege, refusing to leave her home. “Mama… was tired of being shocked by human grief, human cruelty and even by her own patience.”

It’s hard to watch Stalingrad today without your gorge rising at the sheer hypocrisy of its message. Less than a decade after its release, the Russians themselves are laying waste to Ukrainian cities in exactly the same way as the German Sixth Army once targeted Stalingrad. Images in Bondarchuk’s movie, showing bombed-out buildings, look uncannily like those featured in current news reports from cities like Kyiv and Mariupol.

Bondarchuk, who based the screenplay partly on Vasily Grossman’s posthumously published 1959 novel Life And Fate, tries hard to burnish his humanitarian credentials. The story of the siege is bookended in the film by modern-day scenes in which Russians join international rescue workers trying to save German tourists buried under rubble after an “unprecedented” earthquake in Japan. Seventy years after the siege, Bondarchuk suggests, the Russians and the Germans are both part of the same community of nations, their enmity forgotten. That’s a dream which has also crumbled over the last month.

Russian President Vladimir Putin approved of Stalingrad. His followers attended its Moscow premiere. State banks invested in the production. Putin had openly praised Bondarchuk’s earlier film, The 9th Company, (2005), about the tribulations faced by Russian soldiers in the Afghan war, calling it “a tragic story” and “very close to life”.

Today, as his troops batter Ukrainian cities, Putin appears to have forgotten the message of reconciliation hidden beneath all the bloodshed and nationalistic bombast in Stalingrad.

It is a pity that Putin isn’t paying more attention to Russian cinema history. If he looked closely, he would discover that Bondarchuk’s epic follows in a long tradition of Russian movies about local people resisting the overwhelming force of aggressive foreign powers. These movies convey very clearly the personal cost of war – the immense suffering endured by civilians, especially children. They all also invariably end with the invaders being defeated.

You won’t find many films celebrating the swiftness with which the Soviet Union suppressed the Hungarian revolution of 1956, or how Russian tanks were sent into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring in 1968. Instead, underdog stories celebrating the heroism and fortitude of the Russian people under siege are cherished.

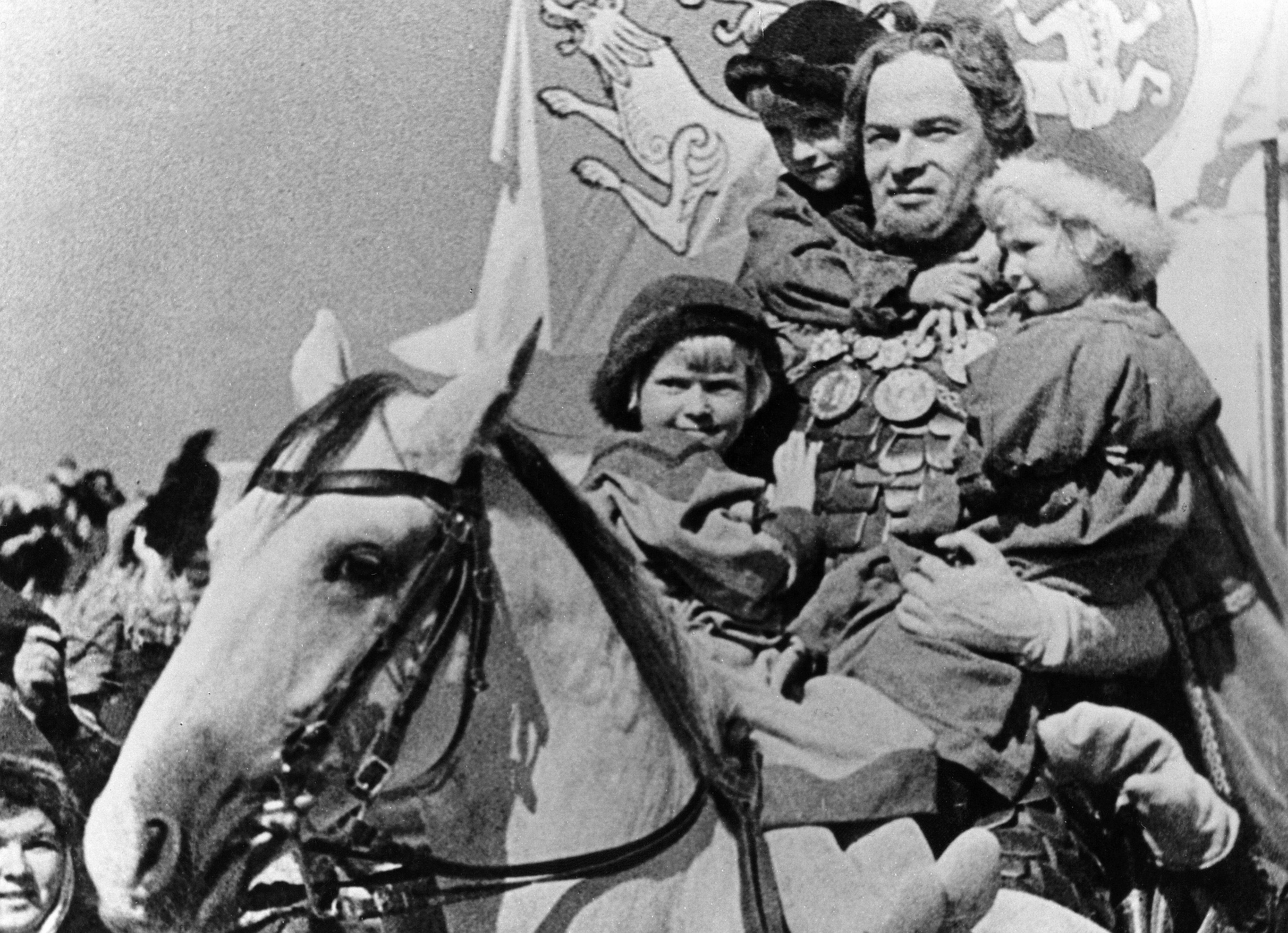

In Sergei Eisenstein’s Soviet historical drama Alexander Nevsky (1938), set in the 13th century, a Russian prince leads an army thrown together in haphazard fashion against the formidable “Teutonic Knights”, who’ve marched eastward toward Novgorod in expectation of an easy victory. He outwits them, beating them in the famous “Battle on the Ice”.

There is a similar dynamic in the epic 1965 adaptation of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, made by Sergei Bondarchuk (Fedor’s father), in which Napoleon’s forces come unstuck in Russia. Such films are complemented by all the Russian Second World War dramas in which, against the odds, and in the face of enormous suffering and through huge sacrifice, the Germans are vanquished.

In The Battle for Sevastapol (2015), the main protagonist is the Soviet female Second World War sniper Lyudmila Pavlichenko, whose nickname was “Lady Death”. She was from Kyiv and the film was actually made as a co-production between Russia and Ukraine.

Many of these Russian movies are intensely propagandistic but they still have a moral force. They show how, in the face of foreign invasion, people forget their differences and come together against a shared enemy.

Foreign writers and filmmakers have often been inspired by stories of Russian dogged resistance against Hitler’s or Napoleon’s forces. There have been several western books and films about the siege of Stalingrad, among them Anthony Beevor’s prize-winning 1998 study Stalingrad, and William Craig’s book, An Enemy at the Gates (1973), adapted by director Jean-Jacques Annaud into a 2001 movie starring Jude Law as the legendary Russian sniper, Vasily Zaitsev.

Zaitzev was one of the greatest Soviet snipers: a hunter who would spend hours waiting for the moment at which he could take his lethal shot. The Soviet propaganda machine made him into a national hero, crediting him with killing over 200 Germans. What makes Law’s Zaitzev such an intriguing figure is his Zen-like state of calm. He is a master of camouflage who can stay immobile in the same location for hours.

The film concentrates on the duel between Zaitzev and the aristocratic German sniper Major König (Ed Harris). This is the equivalent of the shootouts between Clint Eastwood and Lee Van Cleef in spaghetti westerns directed by Sergio Leone, who himself came close to making a film about the siege of Leningrad. In his long coat, with his rifle by his side, Law resembles Eastwood. The difference here is that the backdrop is not the mythical west: it is the burning city in which two huge armies are colliding. Annaud shows the battle between Russia and Germany in microcosm by focusing on the two sharpshooters.

Few western films, though, have matched the mix of surrealism, lyricism, and horror found in the best Russian stories about sieges and invasion. Elem Klimov’s astonishing and deeply disturbing Come and See (1985) follows a teenage Belarusian boy hiding out in the forests with the resistance movement during the Nazi invasion. Flyora’s family has been massacred by the Germans.

The adolescent endures the kind of experiences you see depicted in one of Hieronymus Bosch’s allegorical paintings of the apocalypse. Death and squalor surround him wherever he goes. It’s the throwaway details that are the most shocking – the pile of corpses tidily stacked up behind a cabin after a massacre in a village, or a scene in which, walking down a country path, the boy will suddenly stumble across a severed foot with its boot still on it. Director Klimov had been born in Stalingrad. As a boy in 1942, he had been evacuated from the war-torn city with his mother and baby brother – and he had seen the city and the river Volga ablaze. “Naturally, I am burdened with very strong recollections about that hell,” Klimov explained about his reasons for making a film about the war.

Bondarchuk’s Stalingrad isn’t anywhere near the emotional or artistic level of Come and See. In its lesser moments, it plays like yet another testosterone-driven war movie packed with flashy visual effects. However, no one watching it will have any doubt about either the courage of the soldiers or the terrifying experiences of the civilians trapped inside the besieged city.

Stalingrad was produced by the Jewish-Ukrainian filmmaker and media mogul, Alexander Rodnyansky, one of the founders of the Ukrainian TV channel 1 + 1, which has close ties with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s production company, Kvartal 95 Studio.

Rodnyansky has talked of his “unbearable” shame and sadness about the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In doing so, he has clearly riled the authorities. Last week, Sergei Shoigu, the Minister of Defence, who many believe is running the war in Ukraine, wrote an official letter to the Russian Minister of Culture demanding, in frighteningly Orwellian language, that Rodnyansky and Zelensky be “excluded from the cultural agenda”. In other words, they are being “cancelled”.

Rodnyansky, who also produced two recent Russian Oscar nominees Leviathan and The Loveless, now has to face up to the fact that none of his new projects will receive any state support. As he noted in a statement at the weekend, “The Russian Film Fund, and Russian officials will do their best to undermine everything that I do in the future”.

The irony is obvious. The producer of one of Russia’s biggest box office hits of all time, a film that shows both the intense suffering and the courage of the Russians under Nazi fire in Stalingrad, is now being attacked by the authorities for speaking out against the war in Ukraine

You can safely predict that there won’t be many Russian movies made in future celebrating Putin’s “special operation” in Ukraine. It’s an invasion that turns the narrative of films from Alexander Nevsky to Stalingrad on its head and from which the Russians can emerge only with shame. The material is so toxic that no filmmakers will want to go near it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments