Marvel-lous: How the Russo brothers broke through into the big time

Their Marvel films generated $7bn. Now Anthony and Joe Russo’s wham-bam Netflix thriller ‘The Gray Man’ is breaking records with a reported budget of $200m. But, says Geoffrey Macnab, it wasn’t always the case when they started out making indie films financed on credit cards

The Gray Man, in cinemas this week before coming to Netflix on 22 July, is the most expensive movie in the streaming giant’s history. It’s the Russo brothers’ latest extravaganza with a reported budget of $200m (£170m); a wham-bam thriller starring Ryan Gosling as the James Bond-like CIA assassin Agent Sierra Six and Chris Evans, best known as Captain America, as the uber-villain trying to kill him. There are explosions, fights and chases, many involving the gun-toting Ana De Armas, forever leaping out of the shadows to save Gosling’s life. The new film follows on from the brothers’ four Marvel blockbusters, which generated billions of dollars at the box office. Adapted from Mark Greaney’s first Gray Man novel, it’s expected to spawn yet another franchise, possibly one to rival that of The Avengers, albeit in the action sphere rather than in the world of superheroes.

It’s a measure of how far the Russos have come that you now expect them to make films on such an enormous scale. It wasn’t always like this. When they started their career 25 years ago with an eccentric low-budget flick about three manic Italian brothers who run a hairpiece business in Cleveland, Ohio, they were scrimping and saving.

Pieces (1997) was one of those unsung US indie films financed on credit cards that, as one critic wrote at the time, would “disappear or go straight to video” if it wasn’t for the limited exposure it was given at obscure film festivals.

Anthony and Joe Russo shot much of the film, which had a budget of around $30,000, in their uncle’s wig shop. They had production meetings in their family house which would sometimes be attended by their father, a prominent local politician. If there were crowd scenes, all their cousins and uncles would be invited to swell the numbers.

“They [the Russos] somehow found me. I had a camera at the time and I had a few meagre credits under my belt. I liked what they had to say and the project sounded interesting,” the film’s cinematographer David Litz tells me about how he came on board.

The younger brother Joe was playing a leading role in the movie. Litz likens him to a young Marlon Brando or Al Pacino, all Method tics and quirks, and wonders why he hasn’t appeared on screen more often in subsequent years.

“When he was acting, he relied on Anthony to be quality control… but they both seemed to share the duties pretty equally. They played off each other, almost like musicians. They riffed off each other.”

The soundtrack was full of songs by big-name rock bands. None of the songs had been licensed – and so it wasn’t possible to show the movie outside the festival circuit, one reason why it still isn’t in circulation today.

“When we were shooting it, we were staging camera movements to songs, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and everything else. That’s what hamstrung that film – the music rights,” Litz recalls.

The brothers weren’t optimistic about their chances of breaking through into the big time. After all, they came from Cleveland – and that is a very long way from Hollywood.

“Cleveland is the classic underdog town, full stop,” proclaims Litz, who left the city a decade ago to live in LA. “There’s a lot of grit, a lot of character. That’s a hand-built town, [built] by immigrants, Italians, Polish, Irish. Those people built that town. It’s not an easy town to live in. It’s cold much of the year. Whole industries just shut down and leave. It [Cleveland] is in the Russos’ DNA.”

When Pieces screened in competition at Slamdance – the festival for films too independent in spirit even for Sundance – people were sitting on the floor. The venue was an old office conference room.

However, the established indie darling Steven Soderbergh, who had won the Palme D’Or in Cannes a few years before for Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989) was attending the festival with his own film, Schizopolis. He saw Pieces by chance – and he liked it a lot.

A week after the festival, Soderbergh called up the unknown filmmakers behind Pieces and offered to produce their next movie. He thereby set in motion the chain of events that has led to the brothers’ current box office eminence.

Look at the charts for the highest-grossing movies of all time and you find two of the Russos’ films, Avengers: Infinity War and Avengers: Endgame, very near the top – and the Captain America films not far below. The brothers stand alongside James Cameron as the most commercially successful directors in Hollywood history and yet they still have a surprisingly low profile.

That’s the problem with Marvel superhero movies. The brand is bigger than any individuals behind it. Kevin Feige, the producer orchestrating the Marvel Cinematic Universe, is more likely to get the credit than they are. The Russos haven’t yet mustered so much as a single Oscar nomination between them. They grew up revering Martin Scorsese. Like him, they came from a tight-knit Italian-American community. That must have made it all the more galling when Scorsese called out their superhero films as “not cinema” and as the equivalent to “theme park” rides.

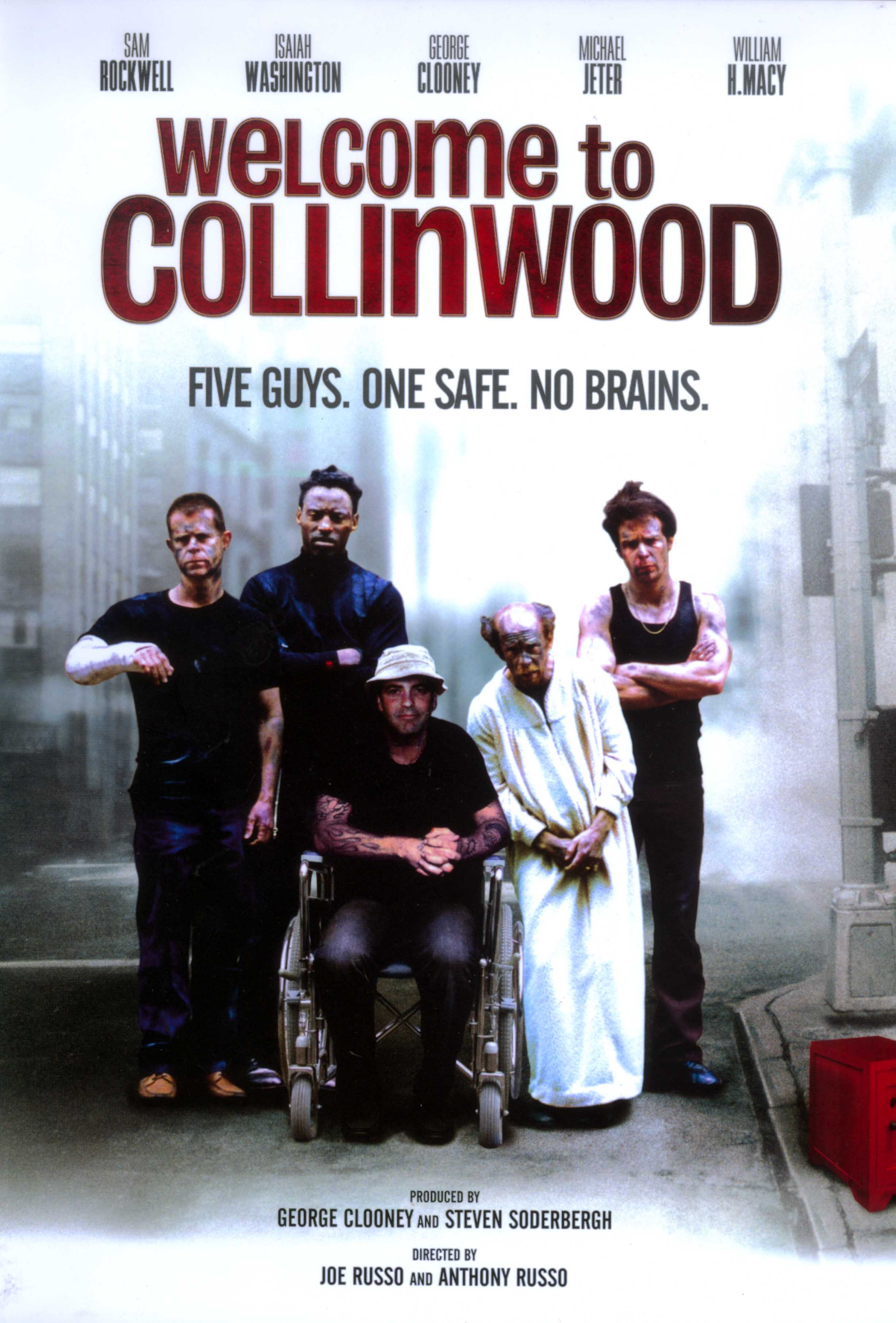

The early Russo brothers film which was taken relatively seriously by the critics was the one that Soderbergh produced, Welcome to Collinwood (2002), their follow-up to Pieces.

Loosely based on the 1958 Italian crime movie Big Deal on Madonna Street and shot on location in Cleveland, it was a gritty, low-budget comedy-thriller about petty thieves and con artists who behave like Ohio’s answer to the hustlers in Damon Runyon’s New York-based stories.

In the film, George Clooney, Soderbergh’s production partner, has a cameo as an obnoxious wheelchair-bound safecracker. William H Macy plays a petty criminal who goes around everywhere with his baby son in a papoose. Patricia Clarkson is the hardboiled femme fatale. Sam Rockwell is the brash would-be boxer who is always getting knocked out in the ring and so turns to a life of crime instead. Luiz Guzman is the thuggish dimwit who thinks he has stumbled on a “Bellini” – gangster slang for the perfect heist.

Although Welcome to Collinwood was selected for the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes, it received a lukewarm reception and did only very modest box office.

At this stage in their careers, the Russos were just like any other members of that vast tribe of aspiring indie US filmmakers, dreaming about emulating heroes like Scorsese or the Coen brothers. Their main strength seemed to be their strong sense of local identity. They had been born a year apart (Anthony in 1970, Joe in 1971), in the Italian part of Cleveland. Their father Basil Russo was a very prominent Cleveland attorney and local politician who had been majority leader of Cleveland City Council in the late 1970s when the city went into budget default.

Welcome to Collinwood may have been a comedy caper but it reflected the social and economic turmoil in the brothers’ hometown when they were growing up. “Cleveland couldn’t have had any worse breaks,” they reflected in interviews about the bad luck that dogged the city in this period.

Bad luck seemed to dog the brothers too, at least as far as the reaction to their movies was concerned. While enthusiasm for Welcome to Collinwood was limited, their next feature, the Owen Wilson/Kate Hudson comedy, You, Me and Dupree (2006), was scorned by many reviewers. “A dire cuckoo-in-the-nest comedy,” wrote The Observer’s Philip French. At least, the film was moderately profitable, largely thanks to Wilson’s rising popularity.

It began to seem that the Russos’ future would be in TV where they had notable success directing episodes of sitcoms like Arrested Development. No one at this stage imagined that the two brothers were about to make some of the highest-grossing films in movie history.

Arguably, the reason the Russos’ Captain America and Avengers movies were such huge hits was that they transcended the conventions of superhero filmmaking. The Russos introduced a bit of that Cleveland grit into the Marvel recipe. The brothers, aided by writers Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, also brought new depths of characterisation to their superhero movies. Their first foray into the genre, Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), was shot on home turf, in some of the same Cleveland locations where they had made Pieces and Welcome to Collinwood. They also returned to the town to shoot their 2021 drama, Cherry, starring Tom Holland.

On the face of it, The Gray Man is the polar opposite to the brothers’ early films. It is driven by action, not character. The hapless, out-of-shape criminals in Welcome to Collinwood and Pieces wouldn’t have the stamina to carry out even the simplest of the stunts that De Armas and Gosling perform throughout the movie. They wouldn’t have the intelligence either to outmanoeuvre adversaries as ruthless as Chris Evans’s Lloyd Hansen, who takes a sadistic and very un-Captain America-like pleasure in torturing his enemies.

Then again, the qualities that Soderbergh noticed all those years ago in Pieces are apparent in the new film too. The brothers may be dealing with extreme chaos and violence in The Gray Man but they remain in control. Whether working on budgets of $30,000 or $200m, their approach is essentially the same – to depict mayhem in the most structured way they can. Like the ultra-resourceful hero played by Gosling in the film, they’re always able to find an elegant way out of the darkest, bloodiest cul-de-sacs.

As Anthony recently told the website Cleveland.com: “We’ve made movies in our career for as little money as you could possibly make a movie for and we’ve made movies for as much money as you could possibly make a movie for and it feels the same from our end.”

As for their old collaborator Litz, from Pieces, he isn’t that surprised by how far the Russos have risen since they were having production meetings in their kitchen in Cleveland. “There was no doubt that these were two passionate, driven, creative guys,” he muses. “I don’t think any one of us on that cast and crew would have predicted they would be directing record-breaking blockbusters multiple times – but I always figured they would do OK...”

‘The Gray Man’ is in selected cinemas from 15 July and on Netflix from 22 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments