It made Scorsese’s heart leap and is still soaring in the list of all-time movie classics: The Red Shoes at 75

As a new teen movie version of Powell and Pressburger’s 1948 film is released next month, Geoffrey Macnab looks back at the making of arguably the most influential British film of its era

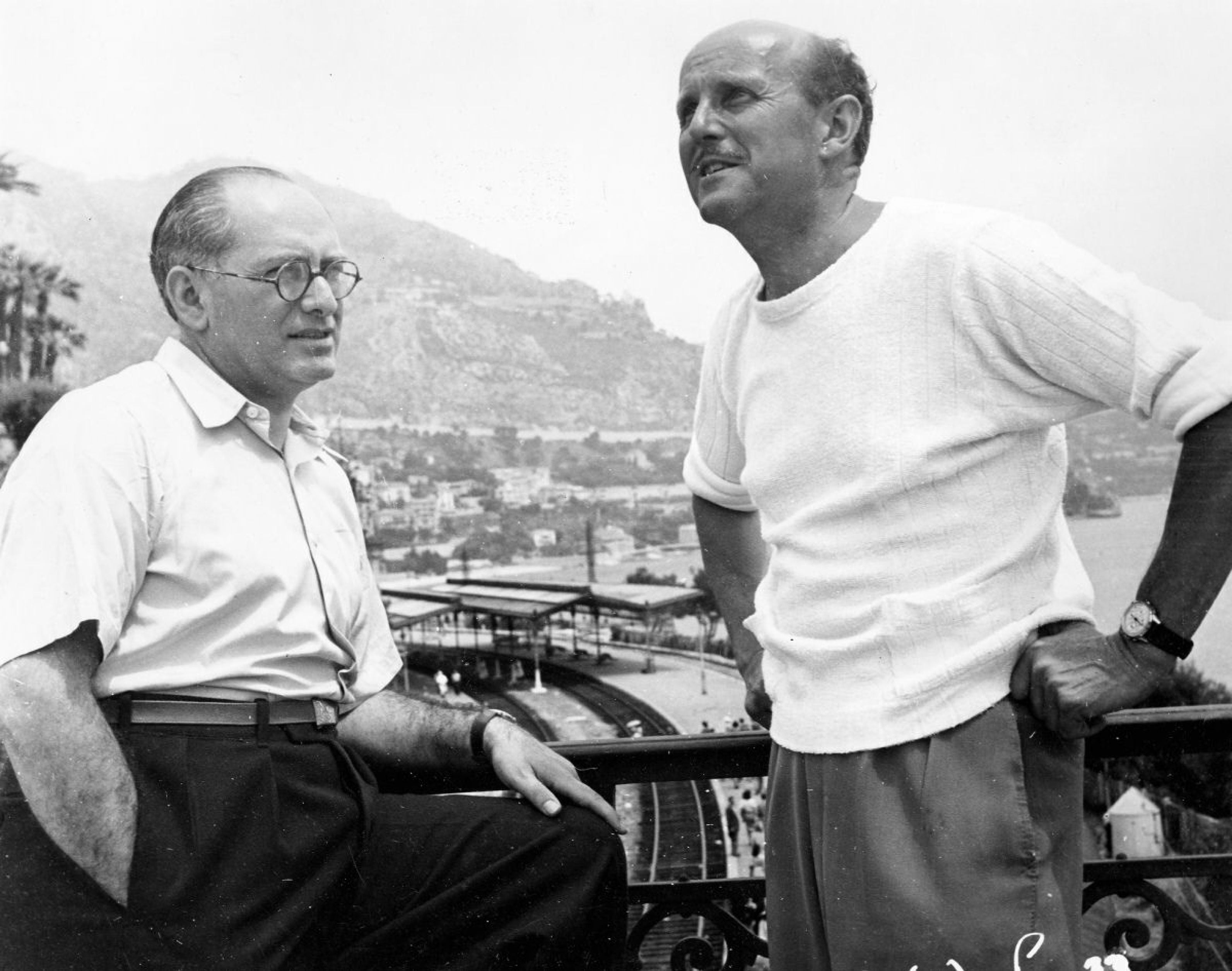

What makes a pugnacious Italian-American director best known for gangster movies like Mean Streets and Goodfellas fall in love with an arty British ballet drama from 75 years ago? This is a question often asked about Martin Scorsese’s passion for The Red Shoes (1948), Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s Technicolor tale of a brilliant young ballerina eventually driven to suicide.

“It’s a film that I continually and obsessively am drawn to,” said Scorsese in a 2009 interview when a restored version of The Red Shoes was shown at the Cannes Film Festival.

He first saw The Red Shoes when he was nine or 10 years old and has continued to watch it again and again. In his New York apartment, he keeps posters and memorabilia from the movie. When he would get home late from a night shoot and couldn’t sleep, he’d often put it on the TV. The film is expected to feature very prominently in his long-gestating documentary about British cinema, if he ever completes it.

A new version of The Red Shoes will be released in UK cinemas next month. The Red Shoes: Next Step is a dance movie from Australia about a brilliant young dancer (Juliet Doherty) whose career is derailed by sudden bereavement, but whose passion for ballet remains. It has been directed by Joanne Samuel, who played the wife of Mel Gibson’s Mad Max in the original 1979 Mad Max movie, and by her son, Jesse Ahern. The film is a coming-of-age story aimed at a younger audience – “[For] all the kids from nine to 14,” Samuel tells me.

“It’s about the grief that artistic pursuits can bring, the blood, sweat and tears of what it actually means to become a performer, you do see that there is a cost involved. You do it because you love it. If you didn’t love it, you wouldn’t put up with it. It’s sometimes like a curse.”

Scorsese is unlikely to become fixated on this new Aussie musical. Nonetheless, the fact it has been made at all underlines the continuing potency of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale from which all versions of The Red Shoes have sprung. Andersen’s strangely disturbing story focuses on a young girl who can’t stop dancing when the red shoes are on her feet. There is the same intensity in the 1948 film.

“Why do you want to dance?” asks the Diaghilev-like ballet impresario Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook) when he meets the young dancer Vicky Page (Moira Shearer), at a reception early on in the Powell and Pressburger movie.

At first, he despises her, thinking she is an upper-class dilettante who regards ballet merely as a hobby. However, when she answers his question with one of her own, “why do you want to live?”, he realises that she shares his obsessive nature. She too is ready to die for her art.

The Red Shoes is as much to do with the Faustian bargains that artists strike as it is about ballet. It is revealing of their neuroses, egotism and cruelty.

“This film is about how art makes monsters of us. There are ballet films before The Red Shoes and ballet films after but it completely changed this sub-genre and this dark streak within them really begins with this film. It’s hard to imagine a sweet and funny ballet film after The Red Shoes,” notes film historian Pamela Hutchinson whose new book on the film is published in the autumn.

Scorsese has often been told that he himself is like Lermontov, the ruthless head of the ballet company who’ll sacrifice anything or anybody in pursuit of artistic excellence. It’s a double-edged compliment but one that he readily accepts.

“There is something about the Lermontov character and the world that he controls that is, I guess, the pool I go back to for sustenance. It has to do with the mystery of art – the mystery of the passion to create and the darker side which can take over,” Scorsese has acknowledged.

From today’s perspective, Lermontov is a problematic character. Walbrook plays him with enormous pathos and charm but that doesn’t hide the monstrousness of his behaviour. Vicky becomes a victim of his destructive jealousy. After she has given her show-stopping performance in the ballet of “The Red Shoes”, he is furious to discover that she has fallen in love with the young composer Julian Craster (Marius Goring). He has Craster drummed out of the company. Vicky leaves with him. Her “idiotic flirtation” destroys Lermontov’s dream of making her the greatest dancer who ever lived.

In his 1994 biography of Pressburger, The Life and Death of a Screenwriter, Pressburger’s grandson, the Oscar-winning Scottish director Kevin Macdonald, makes disturbing observations about the sometimes Lermontov-like behaviour of Powell during the making of The Red Shoes.

“He [Powell] inspired a profound loyalty in those who worked with him regularly, but in general he was an unpopular figure in the British film industry with a reputation for arrogance, bad temper and even cruelty,” Macdonald wrote. Powell is a towering figure in world cinema but he was also a bully with a pronounced sadistic streak. His treatment of the elderly actor Albert Bassermann, who played ballet company designer Sergei Ratov, so outraged Walbrook that the actor – who had also starred in Powell and Pressburger’s 1943 masterpiece The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp – vowed never to work with the director again.

Powell picked on the weakest, those who weren’t in a position to answer back, for example actors in smaller roles, or technicians nervous about working with such an esteemed director. On The Red Shoes, his behaviour was at its worst. “There is no doubt that he [Pressburger] was frequently revolted by his partner’s behaviour,” Macdonald writes of his grandfather.

The other side of the coin was Powell’s charisma and genius – and that was what kept Pressburger with him. He worked the crew of The Red Shoes very hard. The film’s cinematographer Jack Cardiff claimed, however, that it was “an unusually happy unit” and that the director fuelled his collaborators with his own enthusiasm. “He’d encourage me to go ahead with any idea I had, however wild and experimental. Nothing was too risky for Micky and I always knew that if I tried something daring he’d back me up.”

Pressburger’s screenplay was originally written for maverick producer Alexander Korda but was eventually made for the Rank Organisation. It combines the fairytale with elements from the traditional backstage musical. The plot follows young dancer Vicky as she is taken on by Lermontov and eventually promoted to prima ballerina. She triumphs in the ballet of “The Red Shoes”, scored by Craster, but then comes her banishment.

The filmmakers deliberately recruited dancers who could act. This gave the film an authenticity lacking in later ballet-based movies such as The Black Swan (2010) that used doubles for the dance sequences – although Natalie Portman did most of the dancing featured in the final film, according to its director Darren Aronofsky.

Powell’s boldest gambit, though, was to include the entire 17-minute Red Shoes ballet as a standalone sequence. Rank executives were horrified. This was a hugely expensive movie without well-known stars that had gone well over budget. The Rank top brass felt it was far too experimental, pretentious and morbid to appeal to a mainstream British audience. The film has a “U” certificate but touches on some very dark themes, death and betrayal among them.

Critics gave The Red Shoes a mixed reception with several grumbling that it had too much ballet in it for their liking. Nonetheless, the film eventually turned into huge box office hit on both sides of the Atlantic and won Oscars.

In his autobiography, A Life in Movie, Powell attributed its popularity to its vaulting artistic ambition. After the war, cinemagoers, he speculated, were open to movies that challenged them. “I think that the real reason why The Red Shoes was such a success was that we had all been told for 10 years to go out and die for freedom and democracy…and now that the war was over, The Red Shoes told us to go out and die for art.”

It’s hard to think of any other British movie of its era which had such a wide and lasting influence. Filmmakers of Scorsese’s generation, Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma among them, revered The Red Shoes for its formal ingenuity. This was an example of what Powell called a “composed film” in which all the elements – lighting, cinematography, sound, music, production design and performance – were seamlessly integrated. It may have been set in the ballet world but Scorsese picked up immediately on its visual dynamism. Years later, when he made his boxing movie Raging Bull (1980), the rapid camera pans in the first fight between Jake LaMotta and Sugar Ray Robinson were inspired by the similarly frenetic camera work used by Powell in the scenes of Vicky giving a matinee performance in a half-empty Mercury Theatre in London’s Notting Hill Gate.

There’s an irony here. The Red Shoes has inspired generations of little girls and boys to take up ballet in the hope that they can emulate Vicky. It is also the movie that fired the imagination of Scorsese as he set about making some of his most macho movies.

“There are so many reasons for me to dislike the film: its outdated attitude to women, its distorted view of ballet perpetrating the notion that dancers must suffer for their art, the outrageous caricatures and the shouty clichés. But I don’t. I love it,” wrote Deborah Bull, a former Royal Ballet principal, in a 2013 essay for the BBC on the film. She called it “the most genuine film about dancing that I know”.

Hutchinson, who first saw the film when she was very young, talks of how “beautiful and entrancing” she still finds it – but also of how she is shocked every time she watches it by the abrupt and very bleak ending.

“It seems to suggest there is something dangerous about art and that it is such a terrible thing to be afflicted with the artistic impulse, and yet, it fills one with the passion to create something,” she says summing up the paradoxical nature of The Red Shoes. “It is propaganda for art but it also comes with this terrible, terrible warning.”

The BFI major UK-wide celebration, ‘Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger’ runs from 16 October to 31 December. It includes an exhibition at BFI Southbank marking the 75th anniversary of ‘The Red Shoes’, as well as Pamela Hutchinson’s BFI Film Classic, published on 5 October. ‘The Red Shoes: Next Step’ is in UK cinemas on 7 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments