Oliver Stone: How one of Hollywood’s fiercest critics has had to fight to survive the movie game

Stone’s memoir, ‘Chasing the Light’, about his experiences in Vietnam and his early years as a filmmaker is published next week. It’s a reminder of how outspoken and rebellious he is as a filmmaker, says Geoffrey Macnab

To call Oliver Stone a contradictory figure is to understate it massively. The US filmmaker, whose “intimate memoir” Chasing the Light is published next week, is at once a Hollywood insider with several Oscars to his name and one of the US studio system’s fiercest critics. In an interview with the New York Times earlier this week, he described Hollywood as “ridiculous” and “like an Alice in Wonderland tea party”. He railed against how expensive it had become to work there, and how everything has become too “fragile” and too “sensitive”.

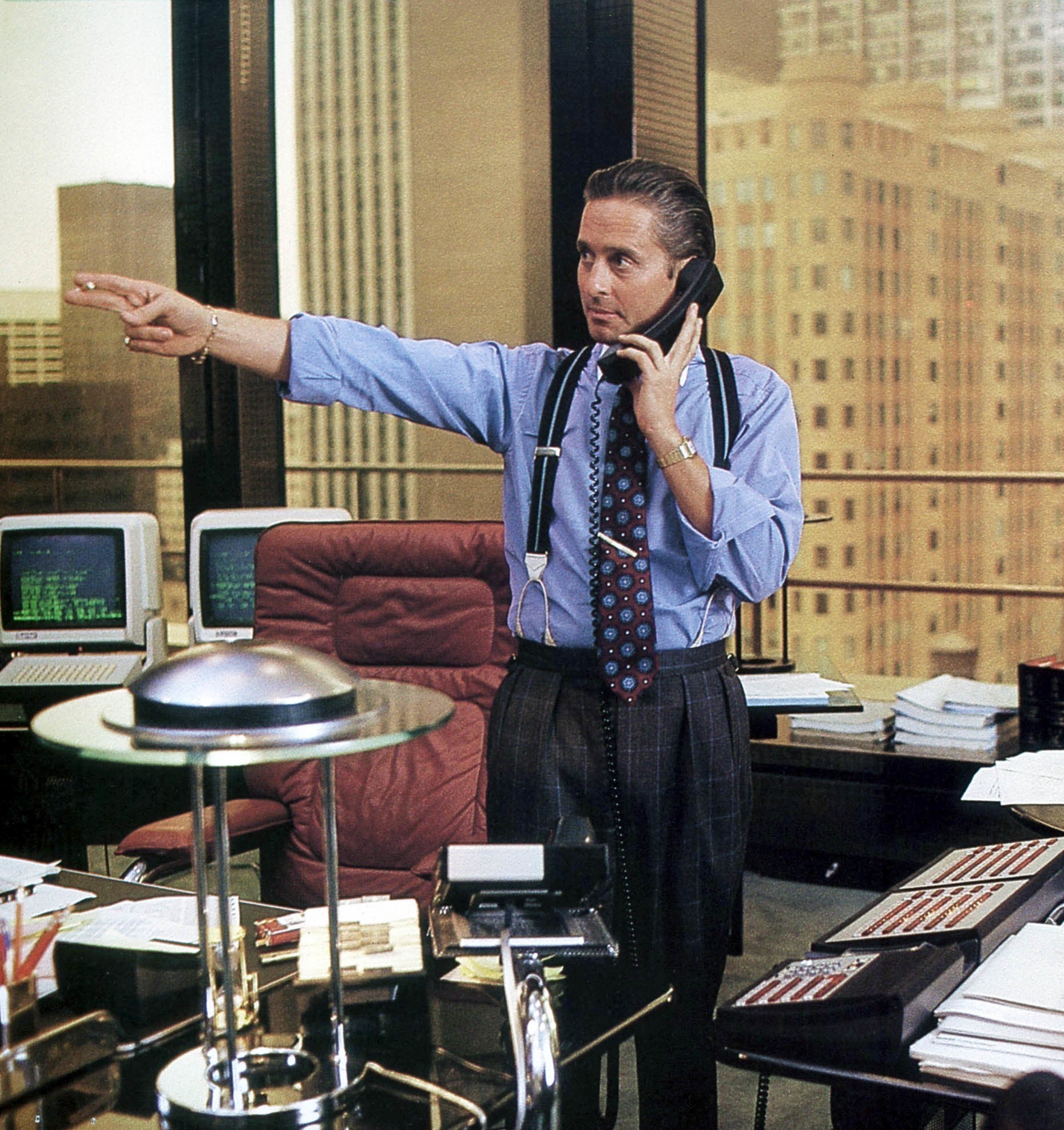

At around the same time that Stone directed Commandante (2003), his low-budget documentary about Fidel Castro, he was busily spending $180m making a film about Alexander the Great. He rails against the materialism in US society and yet, in the period when he was one of Hollywood’s most powerful filmmakers, he created the Mephistophelian banker Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) whose celebration of greed in Wall Street (1987) helped define the 1980s.

Stone makes big, brash movies about larger-than-life US soldiers, politicians, journalists, sports heroes, emergency workers, rock stars, DJs, financiers, and whistleblowers. At the same time, he will often be quoted describing America as “a force of evil” and will use his films to expose corruption and conspiracy at the highest reaches of government.

In his documentary series, The Untold History of the United States (2012), Stone warned how “right-wing forces have always operated freely and openly in the dark chasms of American life where racism, militarism, imperialism and blind devotion to private enterprise festered”. He made his case persuasively and yet he himself is the Ivy League-educated son of a stockbroker who comes from the same privileged background as the politicians and business leaders who’ve allowed this skullduggery to go on. In accounts of his youth, including in early extracts published from his new book, he seems as quintessentially an American figure himself as Gary Cooper in Sergeant York or as one of those adventuresome young heroes in Jack London novels. He’s the merchant marine and aspiring novelist, courageous and hungry for experience.

The story of how Stone volunteered for the US army as an “anonymous infantryman” is part of the mythology that has long surrounded him. He rejected the chance to train as an officer, instead, trying to escape “the fake western life he had grown up in” by becoming a grunt. He saw action, was shot in the neck and won medals for bravery in Vietnam.

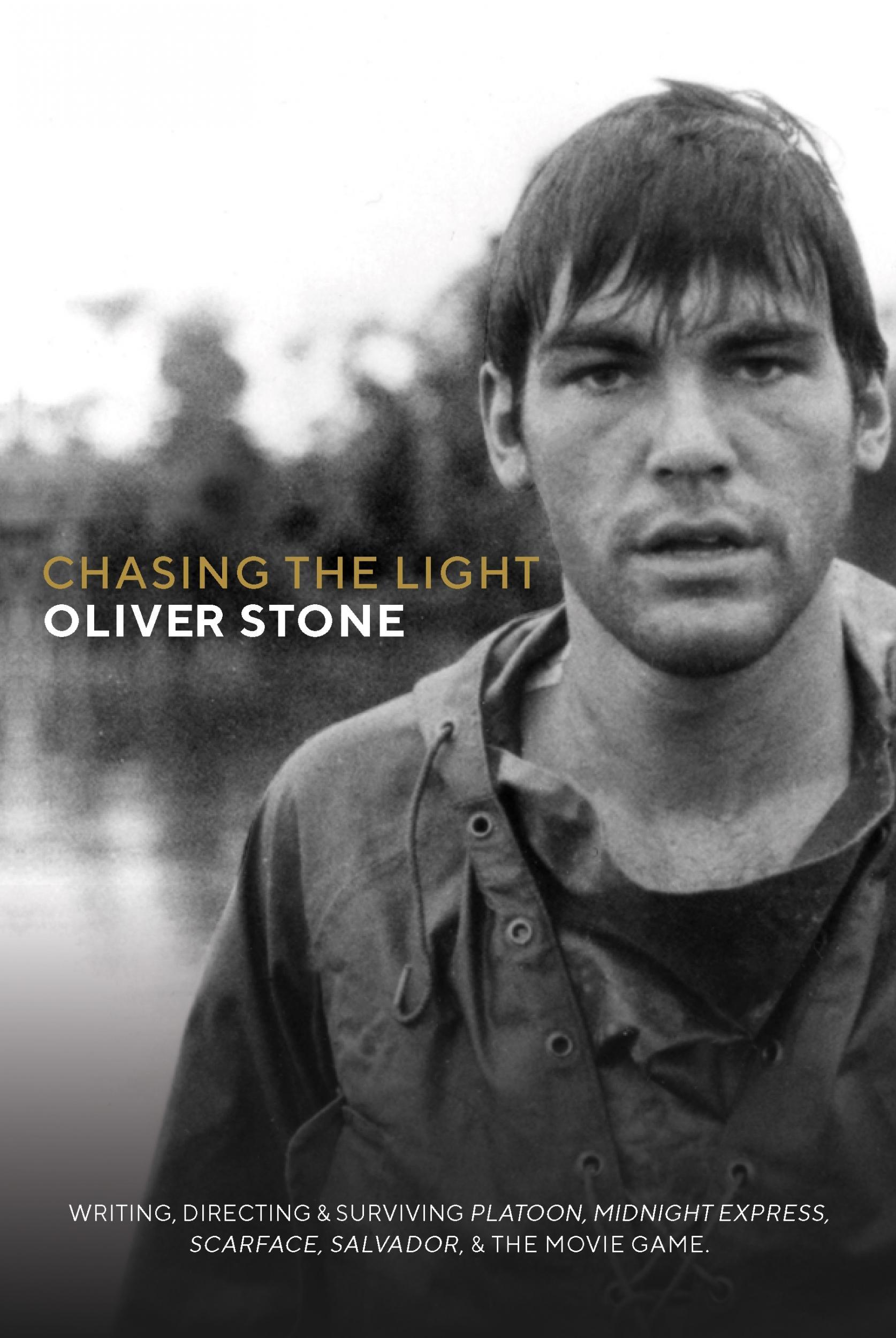

The cover of Chasing the Light is a picture of Stone as a young man, looking at the camera with that strange, haunted expression you find in faces of shell-shocked US soldiers in Don McCullin’s photographs from Vietnam. It tells us that he is authentic. His is a soldier’s story, not a showbiz autobiography. He has seen the darkness. He has actually been on the front line, with first-hand experience of the nightmarish experiences he later set out to show on screen. This is unlike other contemporary directors who have made war movies over the last 40 years such as Stanley Kubrick, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Christopher Nolan, and Kathryn Bigelow.

Stone’s success in Hollywood has been very hard-won. At film school in New York, he was taught by Martin Scorsese. He spent almost 20 years after leaving the army trying to establish himself as a filmmaker. His first two features, horror movies, Seizure (1974), and The Hand (1981), were flops. “They couldn’t defeat me. They’d stopped me as a director but I came back as a screenwriter,” he later said with typical defiance of how he coped with early reversals.

Stone turned out script after script, developing a reputation as a writer of angry, testosterone-driven stories about warriors and outsiders. It didn’t help that he was an abrasive character himself who frequently alienated collaborators. However, those who worked with him almost always recognised his potential. Michael Caine, the star of The Hand and a former infantryman himself, described him as “an extraordinary personality, very volatile and with a tremendous intelligence”.

You can’t help but wonder why Stone as an idealistic young man was so determined to work in the mercenary world of Hollywood in the first place. There is a sense that he threw himself into his film career with the same reckless abandon with which he had approached his time in the military. It’s telling that the subtitle of his new book is “writing, directing, and surviving … the movie game”. By his own admission, his career has been very up and down. As he observes in the introduction to his book, “the constant strain of a dog-eat-dog film business geared to make money can wear any good soul to the bone. The movies give, and they destroy.”

It took him until he was almost 40 to make his breakthrough with Salvador (1986) and Platoon (1986). Both films, released in the US in the same year, were backed by the British company, Hemdale, also later to revive Ken Loach’s career by supporting his 1990 feature Hidden Agenda, a political thriller set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

Hemdale’s boss John Daly wasn’t interested in politics. Stone later said that he had sold Salvador to him on the basis of its two “scuzzbag” heroes, the sleazy American reporter Richard Boyle (memorably played by James Woods) and his raucous sidekick (James Belushi). “Laurel and Hardy go to El Salvador,” was the pitch even if the real purpose of the film was to expose US support of death squads in Central America in the 1980s.

Stone’s attitude towards his British patrons appears to have been deeply ambivalent. Filmmaker Alan Parker provided an entertaining description of the American when he came over to London to work on the screenplay for Parker’s film, Midnight Express (1978) in Soho. “Oliver thought the offices were oddly “Dickensian” and appeared to dislike all things English, including us,” Parker wrote in an essay to mark the film’s 25th anniversary DVD release.

For their parts, Parker and producers David Puttnam and Alan Marshall had little faith in Stone and hoped he would finish the screenplay as quickly as possible so that he would leave them in peace. Then they read the script. “Whatever my personal feelings about Oliver, they soon became instantly irrelevant because of the quality and energy of his first draft screenplay. It was edgy, uncompromising, succinct, full of rage and with a cinematic energy that tore through the pages like an express train from hell,” Parker recalled.

Not that Stone provided a nuanced or subtle portrayal of the Turkish penal system. The film tells the story of Billy Hayes, a young American student arrested in Istanbul for drug possession and sent to prison. His screenplay, which won him his first Oscar, indulged in crude stereotyping of the Turks. Hayes himself later noted that “you didn’t see a single good Turk” in the film.

Stone had spent over a decade trying to raise the money for Platoon. He was told again and again it was too realistic and downbeat to find an audience. This was the era of Rambo and Top Gun. Stone was taking a different tack. Hemdale, though, agreed to support him, on a gamble that Platoon might just be a hit. The epic film was shot on a modest budget in rainforests outside Manila with Charlie Sheen playing Chris, the character based on Stone. The director shot the film with details taken directly from his own experiences in the infantry. For example, he knew exactly what it was like to clean the outhouses.

Platoon reflects the state of mind of the young soldiers it portrays. Most aren’t in the army by choice. They’ve been drafted. “They knew the war sucked. They had that feeling already … they just tried to survive it with dope, good friends and alcohol,” was how the director later summed up their attitude.

The same audiences that had lapped up brat pack movies and films about young friends on the cusp of adulthood like Barry Levinson’s Diner (1982) were also drawn to Platoon. It helped that Stone had assembled such an exceptional young cast. Alongside Sheen as the young soldier and Tom Berenger and Willem Dafoe as the battle-hardened sergeants, the cast also included Forest Whitaker and Johnny Depp.

It would be a mistake, though, to regard Stone as an anti-war director. Platoon wasn’t a modern-day equivalent to All Quiet on the Western Front. Stone’s writing credits included such blood-spattered films as Conan the Barbarian and Scarface. He was the inheritor of a tradition of machismo and screen violence that stretched back to Sam Peckinpah. His own experiences in Vietnam hadn’t turned him into a pacifist. Like many other directors before him, he took a boyish delight in orchestrating complex, explosive battle scenes. It was no mistake that he emerged as a major figure in Hollywood during the 1980s, the era of action movies that made fortunes on VHS as well as in the cinema.

The difference between Stone and most of his contemporaries was that his films had a political dimension. Caine writes of how, even when Stone was directing him in The Hand, the American filmmaker talked constantly of the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963. “His [Stone’s] theory, with which I agreed, based as it was on his experience as a soldier, was that Oswald could not possibly have shot Jack Kennedy with the rifle and ammunition that he carried, at his distance from the car at the time.”

Caine’s observation is revealing. It hints at the approach that Stone takes to all his projects. He never relies on the received wisdom but always tests the evidence for himself. Fifty-seven years after the Kennedy assassination, and almost 30 years after his film about it, JFK (1991), he is still sifting through that evidence. He has been working on a documentary series about Kennedy, JFK: Destiny Betrayed in which he and writer James DiEugenio promise to unveil new information about the assassination. Stone has described the documentary as “an important bookend” to his 1991 JFK feature.

Stone was in his last year at school when Kennedy was assassinated. He was stunned, following the coverage on black and white TV, but didn’t really understand what was going on. In hindsight, he clearly sees the event as pivotal in his own life. If Kennedy had lived, he believes, the US would have pulled out of Vietnam.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of Stone’s Nixon (1995), one of the most ambitious of his political biopics. Typically, Stone approaches disgraced President Richard Nixon’s life as if he is making a very dark gangster movie, showing Nixon (a brooding Anthony Hopkins) draped in shadow in almost every scene.

To his detractors, Stone is a blundering conspiracy theorist who, if he sees a nut, will always look for a sledgehammer to crack it with. To his admirers, he is an inspiring figure: a big name Hollywood director working within the mainstream but tackling contentious subjects from JFK to Edward Snowden that other prominent filmmakers would be far too nervous to go near. He has been around for so long that he is easy to take for granted. If nothing else, his memoir serves to remind us of just how hard he has had to fight first to make it in Hollywood and then to survive there.

‘Chasing the Light’ is published by Octopus Publishing Group on 21 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments