Books of the Month: From George Saunders’ Liberation Day to Alan Rickman’s diaries

Martin Chilton reviews October’s biggest new books for our monthly column

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1968, my late mother opened The Bloomsbury Bookshop in London’s Great Ormond Street, and I grew up experiencing the idiosyncratic, enjoyably eccentric nature of an independent bookstore. Robin Ince captures the joyful atmosphere of all that quirkiness in his charming Bibliomaniac: An Obsessive’s Tour of the Bookshops of Britain (Atlantic Books). The comedian and podcaster’s account of a whirlwind tour of more than 100 stores is full of wry anecdotes and shines with his love of reading. Ince refers to a Japanese word which perhaps applies to those of us who are addicted to books. “My life is summed up by the word tsundoku,” writes Ince, “allowing your home to become overrun by unread books (and still continuing to buy more).”

Fans of the wonderful songwriting and poetry of the late Canadian singer Leonard Cohen will find much to chew over in A Ballet of Lepers: A Novel and Stories (Canongate), written by the musician when he was in his early twenties. Although the stories are uneven, they explore themes – including yearning, sexual desire and alienation – that were mainstays of his magnificent compositions. Another much-missed great is John Le Carré, and the publication of the spy master’s correspondence in A Private Spy: The Letters of John le Carré 1945-2020 (Viking) provides seven decades of his revelations and observations.

Around 7 per cent of people experience a phobia at some point. In The Book of Phobias and Manias: A History of the World in 99 Obsessions (Wellcome Collection), Kate Summerscale offers an intriguing guide to human fixations, including bakomallophobia (a dread of cotton wool).

October is a busy month for new fiction and James Hannaham’s dazzling Didn’t Nobody Give a S*** What Happened to Carlotta (Europa Editions) deserves its place on the radar. The main character is a trans woman and the sexual politics are sharp. Carlotta Mercedes, released from jail after 20 years, is a protagonist with an outspoken voice. Another treat is Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts (Little, Brown), a coming-of-age tale about a 12-year-old called Bird Gardner. The book is as much about fear and injustice as it is about the quest for answers about a missing parent. Two historical novels worth their salt are William Boyd’s The Romantic (Viking), an engrossing tale of a 19th-century soldier facing moral dilemmas, and Heather Parry’s debut Orpheus Builds a Girl (Gallic), which is based on the true story of Carl Tanzler, a German radiologist who disinterred his late “wife” and lived with her body for several years. It’s a compelling, creepy tale – and one that raises relevant questions about who “owns” a woman’s body.

In All In Your Head: What Happens When Your Doctor Doesn’t Believe You? (Hawksmoor Publishing), Marcus Sedgwick delivers a powerful, moving account of what it’s like when you must battle to make the medical world believe that you are ill. A discussion of the stigma that goes with invisible illness is highly relevant in the era of Long Covid, and Sedgwick, a fine writer of fiction for adults and children, recounts his own difficult struggle with honesty and wry humour.

One of the delights of pasta is that you can make delicious meals that don’t cost a pretty penne. There are tasty recipes in A Brief History of Pasta (Profile Books), as food historian Luca Cesari delivers a fine potted history of the Italian food that shaped the world. If you are looking for some light reading morsels, Alex Johnson’s The Book Lover’s Joke Book (British Library) is packed with jests. Funny? Well, judge for yourself by this example:

Who was JRR Tolkien’s favourite singer? Elvish Presley.

If you’re in the market for something beautiful and deep, The Penguin Book of French Short Stories (two volumes, 84 authors, 864 pages, edited by Patrick McGuinness) is a sumptuous treat for any book lover.

Novels by Cormac McCarthy, Barbara Kingsolver and John Irving, short stories by George Saunders, the diaries of Alan Rickman and a history of the England men’s football team are reviewed in full below.

Madly, Deeply: The Alan Rickman Diaries by Alan Rickman

★★★★☆

John Major walked up to Alan Rickman and praised the actor for giving us all “so much enjoyment”. “’I wish I could say the same of you,’ was the unstoppable reply. He had the grace to laugh,” Rickman notes about the former Prime Minister, in a diary entry for 3 July, 2011. Rickman, so magnificent in roles such as Die Hard’s villainous Hans Gruber, or in Truly, Madly, Deeply or as Professor Severus Snape in the Harry Potter franchise, provides more enjoyment in these astute and entertaining posthumous memoirs.

In Madly, Deeply, which runs from 1993 (after Rickman’s work at the Royal Shakespeare Company) to his death from pancreatic cancer in January 2016 at the age of 69, editor Alan Taylor has distilled more than one million words of memoir into a 480-page book of day-to-day recordings.

Rickman is adroit at deflecting attention from his personal life and emotions, but he offers a fascinating guide to life as an actor and what it’s like to be at the centre of fame. His judgements can be succinctly damning – Liam Gallagher (“tosser”), Kevin Spacey (“self-satisfied”) Ewan McGregor (“self-involved to a jaw-dropping degree”) – or full of admiration, as in the case of Paul Newman. One entry simply reads “four great words – I MET TOM WAITS”, who turns out to be “stylish, gentle”. Before he died, Rickman left instructions that Waits’s moving ballad “Take it With Me” was to be played at his funeral.

His judgements on celebrities are often penetrating (Ricky Gervais and Russell Brand, for example) and Rickman remarks after a dinner with John McEnroe that “he doesn’t mind gossip – no one likes Rusedski”. Rickman was a keen tennis player, and it’s a shame that nothing more detailed than “Dan Day-Lewis arrives to play tennis” is included for 27 May, 2002. It’s an intriguing sporting contest to imagine. And who on earth won?

Some entries are pithy, some long, and the subjects vary from the monumental to the everyday problems of back pain, stress, and travel hitches. Strip away the grand occasions and very occasionally the memoir reads like a dull day-to-day appointments board on a fridge, although that is infrequent, and a minor grumble.

One distinct thrill is reading Rickman’s short, sharp film appraisals. Among these are for Jurassic Park (“what the hell is the plot? Great dinosaurs”), Pulp Fiction (“brilliant and empty”) and his appraisal of a flaw in The Shawshank Redemption, in this case the flood of inmates with neat haircuts. “When will a director tell a hair person to STOP tidying everyone up – it’s an awful reflex action,” Rickman notes. He thought Die Hard held up 10 years after its 1988 release, noting “it still works like none of the others. Real energy, perfect camera work, wit and style”.

Rickman doesn’t hide his disdain for “lazy” or “idiot” journalists, and he writes interestingly about his regular interactions with Labour politicians such as Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair. He is especially withering about former Home Secretary Charles Clarke. “Never trust a man with two-day growth, who also stuffs his face that much,” writes Rickman.

These diaries are a reminder of a warm and witty man, one who could see the quirks of life and his own part in the absurd drama of existence. One entry, when he was in Edinburgh in November 1994, made me smile. “Thank you to the middle-of-the-night pissed joker who rewrote my breakfast order so that I had fish and pineapple juice delivered at 7.20am instead of toast and coffee at 8.30…” recalls Rickman. Can’t you just picture his face as he opened the door to the waiter?

Madly, Deeply: The Alan Rickman Diaries is published by Canongate on 4 October, £25

Liberation Day by George Saunders

★★★★☆

Perhaps it is my advancing years, or a mounting dismay about the state of the world being ruined for future generations by the venal, self-interested politicians and corporations in control, but I found myself choked up reading “Love Letter” by George Saunders. It’s one of nine short stories in Liberation Day, the new collection from the author of the Booker Prize-winning Lincoln in the Bardo.

“Love Letter” is a poignant, emotional missive from a grandfather to grandson, in a none-too-distant future in which autocratic throwback politicians, inspired by a “clownish” leader, are imposing their unrepentant authoritarian ways on society. The old man’s tender handwritten letter to a grandson who has been a “perpetual delight” is essentially warning him to toe the line. What makes it so utterly moving is that the old man is full of regret, guilty over his complacency and aware of his own reasons for urging caution. “When you reach a certain age, you see that time is all we have,” says the loving grandfather.

Some of the dystopian/fantasy tales in Liberation Day left me cold, but there are other terrific stories in this latest Saunders collection – especially “Sparrow” and the seven-page tour-de-force “My House”. The book is worth reading for “Love Letter” alone, however.

Liberation Day by George Saunders is published by Bloomsbury on 18 October, £18.99

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

★★★★★

When she was in her early twenties and starting to “write more seriously”, Barbara Kingsolver used to study Charles Dickens for plot and analyse John Steinbeck for theme. The former Orange Prize for Fiction winner, now 67, has harnessed both these inspirations for an extraordinary reimagining of David Copperfield set in the mountains of Southwest Virginia at the onset of the opioid epidemic. Demon Copperhead is a superb piece of storytelling and a book that helps navigate the chaos of modern America.

The language is potent, the twists good and the protagonist, Demon, a young Appalachian boy scrabbling for survival from the moment he is placed in foster care, is a character who will stay in your thoughts, as he confronts addiction, love and the elusive search for happiness. Prescription drug addiction is one of the many worrying problems of our time and Kingsolver’s rumination on it is a true highlight of 2022 fiction.

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver is published by Faber on 18 October, £20

The Last Chairlift by John Irving

★★★☆☆

I saw a joke on Twitter about needing a forklift to be able to pick up John Irving’s The Last Chairlift, his longest novel, which comes in at a whopping 889 pages.

The novel, which was originally titled Darkness As a Bride, is an emotionally complex, multi-generation tale of love, evolving sexuality, death, ageing memory and identity. On the opening page, the narrator Adam declares that “not all ghosts are dead” as he returns to the Hotel Jerome in Aspen, Colorado, the place where his teenage mother, slalom skier Rachel Brewster, conceived him in 1941. The answers to his origins aren’t necessarily the ones Adam wants. And he does see ghosts.

Irving also tips a frequent nod to his literary heroes Charles Dickens and Herman Melville (Em as Ishmael is the title of the fiftieth chapter, in honour of Moby-Dick) and he draws on his own skills as a Hollywood writer for some of the Aspen screenplay script sections. Adam grows up in an unconventional family and Irving is his usual deft self about showing the strangeness of life in a time span that has moved from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s sense of duty to “Trump’s pussy-grabbing”.

The Last Chairlift is the first novel in seven years from Irving, who turned 80 in March this year. At times it is sprawling and sluggish, yet it has some of the moments of brilliance that have lit up previous triumphs such as The World According to Garp, The Cider House Rules and A Prayer for Owen Meany (my own favourite Irving).

The Last Chairlift by John Irving is published by Scribner on 18 October, £25

The Passenger by Cormac McCarthy

★★★★☆

Sixteen years after the Pulitzer-winning The Road, 89-year-old Cormac McCarthy returns with The Passenger, the story of a melancholy salvage diver in New Orleans called Bobby Western. It is the first in a two-volume work, with the coda, Stella Maris, out in November.

“Everything is painful to me,” says Western, the son of a physicist who worked on the atomic bomb. In 1980, hired as a deep-sea diver to investigate a private plane crash in the Gulf, Western begins to get “an ugly feeling” about the “accident”, especially when it becomes clear that there is a body missing. As government agents begin to harass him, and colleagues start dying in unexplained ways, the novel quickly becomes a cryptic conspiracy thriller. It’s no coincidence that the bloody death of JFK comes into a later conversation.

This narrative is intertwined with the story of Western’s sister, Alicia, a mathematical genius and paranoid schizophrenic who died by suicide. His grief and unatoned love for his sister is at the heart of a tale about a haunting family legacy. In flashbacks of Alicia’s visual and auditory hallucinations, we get to eavesdrop on her weird, unsettling philosophical conversations with a character named the Thalidomide Kid.

McCarthy is a man who can create indelible images (the coin toss in No Country for Old Men) and he does so again in The Passenger, including the corpses in the water, swollen in their clothes and rising up like circus balloons to hug the salvage diver. There are also poignant accounts of run-down American towns and nerve-jangling descriptions of the victims of Nagasaki.

McCarthy’s fiction is hugely impressive – I remember being bowled over reading All the Pretty Horses in 1992 – and the same peculiar twists of humour and darkly comic intelligence shine through this latest work. The Passenger is an enigmatic, morbid novel, but sometimes its skittishness – and small print (lots of it in italic) – make it a difficult read.

It is good to have McCarthy back, though, reminding us of his unique gifts. “Maybe you’re just a hoarder of misery. Waiting for the market to rise”, a friend tells Western, one of many pungent memorable lines.

The Passenger by Cormac McCarthy is published by Picador on 25 October, £20

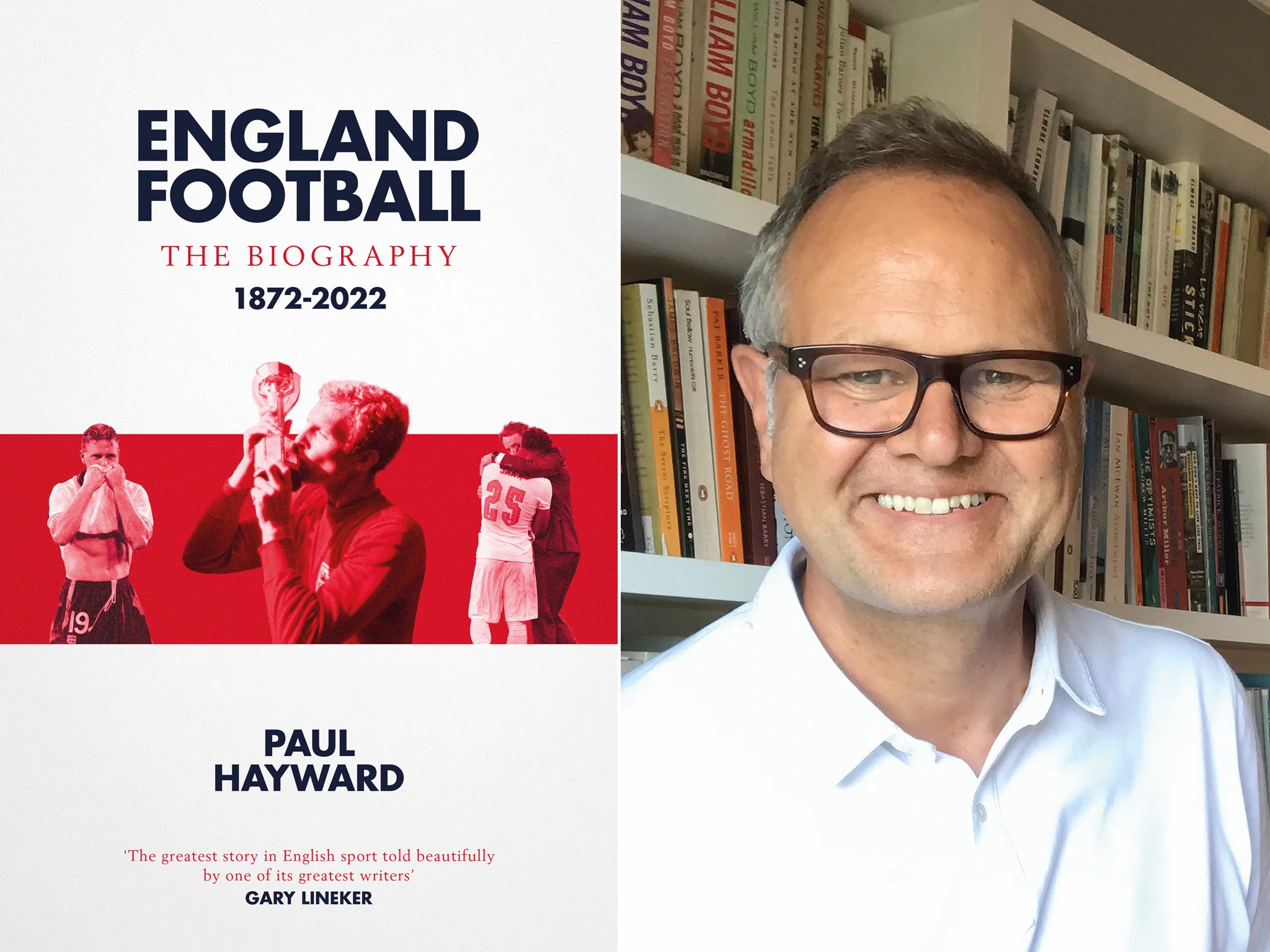

England Football: The Biography 1872-2022 by Paul Hayward

★★★★★

As if it wasn’t devastating enough for the volatile Paul Gascoigne to be called into Glenn Hoddle’s hotel room to be told he was being axed from the 1998 World Cup squad; apparently Hoddle delivered his discarded player the miserable news while playing a Kenny G CD in the background. Is it any wonder that Gazza reportedly “flew into a total rage” and punched a lamp?

As it turns out, that World Cup, with a botched penalty shoot-out and a red card for David Beckham, was yet another tournament failure in the painful history of the England football team. Paul Hayward, author of England Football: The Biography 1872-2022, says he always detected a “defensive wincing” when interviewing players about these big tournament defeats.

To mark the 150th anniversary of the first international (a 0-0 draw between England and Scotland), Hayward has written a compelling, brilliantly researched history of the national side. Although the early sections are obviously distant in terms of time, they are nonetheless engrossing and include a riveting account of England’s 1934 clash with Italy, something that reads more like a war despatch than a match report. Hayward, an award-winning chief sports writer, also casts a dispassionate eye on the controversy over the 1936 England team giving a Nazi salute to Hess, Ribbentrop and Göring.

The theme of “squandered talent” in the immediate post-war years was expunged by the 1966 World Cup win over Germany. Hayward offers a riveting analysis of the taciturn coach Alf Ramsey. He could be blunt (“f*ck off, son”, Ramsey told Terry Venables, when the ambitious young Chelsea player tried to cosy up to him on the basis of their shared Dagenham roots), rivalling President Nixon when it came to swearing in front of staff.

Although the book is restricted to the men’s game, Hayward is clear about the long-standing chauvinism of the Football Association. The wives and partners of the 1966 heroes were – because of “patriarchal cruelty”, in the author’s words – sent into a separate dining hall on the night of the Wembley triumph, while FA and League bureaucrats hogged the tables in the main banqueting hall alongside Geoff Hurst, Bobby Moore and Co.

In a different era, as a young football writer, I wrote to England manager Bobby Robson, who kindly telephoned back and invited me to the old FA headquarters. We spent several hours chatting openly about football and during that visit to Lancaster Gate, I saw for myself the blinkered nature of the organisation. Brian Clough, a man rejected by the old guard, referred to the “blazer-wearing bastards” of the FA and “insularity” is a word that crops up regularly in Hayward’s book. Robson was one of the 18 post-Ramsey managers who failed to deliver a trophy to the (men’s) side.

Robson is one of eight England managers I’ve met and interviewed over the years and the quirks, personality flaws and sheer bizarreness of some of these characters would occupy an international conference of psychiatrists, let alone a 600-page football book. Hayward covers them all deftly, however, including the “tactics-phobic” Kevin Keegan; greedy Don Revie and Sam Allardyce (both undone by financial-related scandals); Sven-Göran Eriksson, a man with such a lust for celebrity that he hired sex offender Max Clifford to do his PR; the hard-line Fabio Capello (“to win a player’s respect you have to put a razor blade up against his arse,” said the Italian, in charge of the disastrous 2010 campaign); the ill-fated “do I not like that” Graham Taylor and the woebegone Steve McClaren.

There is also, of course, the weirdness of the Hoddle era, when, according to defender Graeme Le Saux, it was like a “rather eccentric health farm”, with players hooked up to intravenous drips a couple of hours before games. Hayward notes, of course, that Hoddle lost his England job after reportedly telling The Times football correspondent Matt Dickinson that the disabled were reaping karma from a previous life.

Football writing can be clunky and boorish, but at its elegant best it is capable of capturing the intricacies and intrigue of some of the strangest human drama around. The game is often nasty and unedifying and Hayward does not shy from exploring the bigoted fans, racist players and hooliganism (the “English disease”) which have blighted its reputation. He has assembled revealing tales from insiders, including the account of how (unnamed) England players sexually assaulted an air hostess from Bulgarian Airways during a flight to a game in 1974.

There are also crisp, entertaining accounts of long-gone matches (something that always tests a football journalist re-treading the paths of old boots) and it was fun to read the account of England’s momentous 5-1 win over Germany in Munich in 2001. According to Jamie Carragher, hat-trick hero Michael Owen “rushed into the dressing room [at half-time] like a man possessed, and announced, ‘This lot are f*cking shit!’” Ah, football: it truly is the beautiful game sometimes.

The book ends with Gareth Southgate, “a statesman manager” in Hayward’s view (one I share, having worked with him when he was a columnist for the Evening Standard), a leader who outspokenly advocates social justice. Southgate’s next test is the upcoming World Cup in Qatar. Any reprint will presumably cover whether his (of late, struggling) England team finally managed to overcome the “small mentality” (Cristian Ronaldo’s phrase) that has let the team down on so many occasions. As a pre-match warm-up, however, Hayward’s superb book is a must for any true football fan.

England Football: The Biography 1872-2022 by Paul Hayward is published by Simon & Schuster on 27 October, £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments