Books of the month: From David Mitchell’s Utopia Avenue to Frances Cha’s If I Had Your Face

Martin Chilton reviews five of July’s releases for our monthly book column

Three powerful memoirs out in July are part of what is more like the usual monthly publishing avalanche. Woman’s Hour presenter Jenni Murray writes about her own battle with obesity in Fat Cow, Fat Chance (Doubleday). Murray admits to the pain she’s suffered after getting vile abuse about her size. Her candid book is an eloquent reminder that “fat-shaming is hate speech”.

Fragments of My Father (4th Estate) by Sam Mills is a poignant memoir about being a carer for a father who suffered from mental illness. Mills melds her own touching story with reflections on the literary figures – including Zelda Fitzgerald – who have been through similar struggles. The third bitingly honest autobiographical tale is Terri White’s Coming Undone (Canongate), in which the Derbyshire-born editor-in-chief of Empire movingly documents how she rebuilt her life after incidents of physical and sexual abuse.

There are a host of terrific novels out in July, including John Boyne’s heavyweight A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom (Doubleday) and Caoilinn Hughes’s The Wild Laughter (Oneworld), which is full of energy and mordant wit. Kathleen MacMahon’s impressive love story Nothing But Blue Sky (Penguin Ireland) is a tender dissection of marriage.

Although the reality of enjoying holiday reading on a beach may seem far-fetched at the moment, Santa Montefiore’s Here and Now (Simon & Schuster) and Lisa Blower’s Pond Weed (Myriad Editions) are entertaining “staycation” stories to take you away from things in the meantime.

Thriller fans will find much to enjoy in T W Ellis’s A Knock at the Door (Sphere) and Ryan Gattis’s The System (Picador). Also recommended is Sabine Durrant’s chilling Finders, Keepers (Hodder) and Peter James’s Find Them Dead (MacMillan), another first-rate detective superintendent Roy Grace adventure. Dorothy Koomson’s All My Lies Are True (Headline) is the taut follow-up, 10 years on, to The Ice Cream Girls.

I enjoyed two new coming-of-age tales: Matson Taylor’s offbeat The Miseducation of Evie Epworth (Scribner) and the gently comic, compassionate Tennis Lessons (Doubleday) by Susannah Dickey. Eley Williams’s novel The Liar’s Dictionary (William Heinemann) is an imaginative treat. “Dictionaries are heady things,” Williams says in the preface to a clever, playful debut about a young woman digitising a 19th-century dictionary. Reproduction by Canadian poet Ian Williams (Dialogue) is the lyrical tale of an odd-couple relationship between a West Indian student and a wealthy German heir.

Folk musician John Martyn makes a cameo appearance in David Mitchell’s new music-based novel Utopia Avenue – a far cry from the volatile man dissected in Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn by Graeme Thomson (Omnibus Press). This excellent biography includes accounts of Martyn’s appalling violence towards his wife Beverley.

Richard Holloway’s book reflecting on the universe, along with novels from Mitchell, Amanda Craig, Arlene Heyman and Frances Cha, are reviewed in full below.

The Golden Rule by Amanda Craig ★★★★★

July is off to a flying start with Amanda Craig’s The Golden Rule. The addictive plot line – which pivots on a reckless murder pact that has deliberate echoes of Strangers on a Train – is the vehicle for a wide-ranging, incisive portrait of contemporary Britain.

Craig’s new novel follows her habit of cross-pollinating from previous books. The protagonist Hannah appeared as a child in A Private Place. Hannah is now a single parent, broke and disconsolate, struggling to cope with an unfaithful, abusive departed husband who won’t honour his financial responsibilities. When her mother’s illness forces Hannah to travel from London to her native Cornwall, she chances to meet a manipulative, glamorous female stranger who suggests a deadly solution to their seemingly similar troubles. All is not what it seems, of course, and Craig builds the tension to the dramatic, thrilling finale.

The Golden Rule mulls over what may drive a woman to the point where she would even consider murdering a fellow human being – domestic violence is not limited to man-on-woman in Craig’s story – and has pertinent things to say about the way women suffer from insidious workplace sexism and harassment.

Hannah’s misery is sharply drawn – no surprise given Craig has admitted that she endured a grim time as a graduate trainee in an advertising agency. Likewise, Craig brings her experiences working as a cleaner during the recession of the 1980s to bear on her telling account about the demeaning way that Hannah is treated when she takes work as a cleaner in middle-class homes.

The Golden Rule casts a cold observant eye on our post-Brexit, class-ridden, broken nation. Craig shows a land disfigured by an obsession with wealth and status, one unable to leave its racism behind, some people still unable to see how wrong it is to call someone “a darky”.

There is a rural/urban aspect to the book, and Craig uses dispassionate wit to reveal divisions between a Leave county like Cornwall and a heavily Remain place such as London. Cornwall is “stuck out into the Atlantic like the bunioned foot of Britain”, a place where “tradition is the opium of the people”. At the same time, Craig makes clear why “the race the Cornish most objected to was Londoners”. Many of them are uncaring tourists or wealthy interlopers. Hannah’s Cornish relatives joke about the grey, thin “London look” as “like a plant that’s been kept in the dark”.

Society’s wider turmoil is reflected in Hannah’s inner struggles. She has to confront her own morality, discover what she truly stands for, and look closely at the narrative that someone else is trying to sell her. As she battles with this and decides whether she will murder the Cornish husband of the train “stranger” Jinni, everything is thrown into confusion by the Beauty and the Beast-like relationship she develops with Stan, her intended victim.

Among the many enjoyable aspects of the novel is the passion Hannah displays for reading. She argues about books with Stan, a video game designer who tries to convince her that “The Last of Us is a bit like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road”. Hannah takes exception when Stan calls Jane Austen “the laureate of female hopelessness”, arguing that the author of Pride and Prejudice was “revolutionary” because her heroines marry for love not money.

“To sink into a story, old or new, was to enter another world of beauty, emotion, intrigue and danger, a better world in which people talked to each other about what mattered, and things happened,” Hannah says. Her words could easily stand as an apt summary of the delights of The Golden Rule.

‘The Golden Rule’ by Amanda Craig is published by Little Brown on 2 July, £16.99

Artifact by Arlene Heyman ★★★★☆

Arlene Hayman, a 77-year-old former psychiatrist who studied literature under Bernard Malamud, has followed her short story collection Scary Old Sex with her debut novel, Artifact.

The action takes place from the 1950s to the 1980s. This transitional period for women in America is evident in the life and career of protagonist Lottie Kristen – a cell biologist who has to battle against misogyny in science as she forges a career doing what she loves.

Lottie, named after Charlotte Bronte and thankful that her grandmother’s affectionate nickname stuck, was a forthright, inquisitive child (her idea of fun on Christmas Day is to dissect a cat), who quickly earned a reputation in the small rural Presbyterian town in which she grew up for being “too smart for a girl”, someone who will “just get herself into trouble in the end”.

Heyman draws a deft portrait of Lottie’s childhood and adolescence, a troubling time for a girl who worries that she is a “freak” because she is “sexually forward” in the conservative post-war era. She clashes with her controlling, hostile father. “I don’t want the whole house stinking of formaldehyde,” he hisses at her. “Why don’t you just piss all over the place.”

Lottie’s compulsion for independence, her desire to pursue the mysteries of her life – whether that is in a laboratory or within her own body and mind – come in an era when it was not unusual for women to feel “mortification” at having a daughter rather than a son. In the acknowledgements, Heyman tellingly reveals her father Jerome taught her that “any man who had a mother ought to be a feminist”.

Heyman’s portrait of the collapse of Lottie’s marriage to a young football star, whose career is ended by a knee injury, is full of insights. “Some part of Charlie that had been gentle and curious despite the insular family he’d come out of, some door, some window, had turned into a wall; he had grown harder,” says Lottie. She will not be domesticated and resists being left to feel “shadowy and birdbrained and cranky”.

The chaos of biological existence continues to captivate Lottie throughout her own turbulent journey through life and the different loves it brings. Lottie is a remarkably resilient character, especially given the shocking things that occur in the book, including a horrendous encounter with a man from her past. You sense that Heyman has used all her life experience to write an intimate portrait of family life and an uplifting tale of a woman determined to exist on her own terms.

‘Artifact’ by Arlene Heyman is published by Bloomsbury on 9 July, £16.99

Utopia Avenue by David Mitchell ★★★★★

David Mitchell’s eighth novel is an ambitious, rambunctious, hugely enjoyable tale of a band’s rise to fame in 1967 and their abrupt, tragic end. Mitchell wasn’t around for much of the Sixties – the acclaimed author of Cloud Atlas was born on 12 January 1969, the day Led Zeppelin released their debut album – but he has exuberantly captured that decade in Utopia Avenue.

In the novel, a Canadian music manager bolts together four memorable, curious characters – the oddball guitarist Jasper de Zoet, the blunt-speaking Yorkshire drummer Griff Griffin, the picaresque working-class bass player Dean Moss and the introspective keyboard player Elf Holloway – to create a band. Fame and fortune seem a distant dream, especially after a disastrous debut, but the quartet have true talent and a special chemistry that propels them to stardom, opening doors to meeting some of the greatest musicians of the 20th century.

Real-life stars are seeded throughout this fable-like story, including David Bowie, Rod Stewart, Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon, Janis Joplin, Frank Zappa, Humphrey Lyttelton, Leonard Cohen, Gerry Garcia and even a teenage Jackson Browne. Folk singer John Martyn “turns his wild man’s head” as he wishes Elf good luck before a gig (although, having met him a few times, I would hazard that the real Martyn would have added a profanity or two) and an unctuous Jimmy Savile gets a cameo in which he is mocked by Steve Marriott. “She’s a bit old for you, Jimmy, surely… I mean she’s over sixteen. Legal, like,” are the words Mitchell puts into the mouth of the late frontman of Small Faces, at a party after Utopia Avenue have appeared on Top of the Pops. Wishful retrospective thinking, perhaps.

Each chapter name is the title of a song and Mitchell includes original song lyrics and vivid descriptions of musicians such as Joni Mitchell (“her voice pulses, dives, aches, swivels, regrets, consoles, avows”). Music aficionados will appreciate the Easter eggs Mitchell scatters in the pages, such as wry asides about the Rolling Stones and Chess Records, and the inclusion of the sort of “folk-bore” who buttonholes Elf to “take her to task for sullying the purity of the 1765 version of ‘Sir Patrick Spens’”.

There is plenty of good jazz name-dropping, too, including mentions of Dave Brubeck, Art Blakey, Miles Davis and Billie Holiday, although I did wonder how many people would understand quite why it’s so important to Griff that a photographer captures him “looking like Max Roach” (the drummer who was a pioneer of bebop). There are constant little touches that resonate, including Jasper’s description of hearing Big Bill Broonzy play on a porch in the Netherlands and the emotional pull of Julie London singing “Cry Me a River” to someone whose heart has been shattered.

Mitchell’s story features some of the typical dramas around a band – ego clashes, groupies, rip-off promoters, fellow musicians who plagiarise, record-company parasites – as well as ever-present dangers of late-night travel, violence and freely available drugs. Plenty of acid is dropped and cocaine snorted in Utopia Avenue, with musicians gravitating to Soho, a place where “the usual rules don’t apply”.

As well as the story of a band, this is a portrait of England itself half a century ago, a time when bedsit signs read “BLACKS & IRISH NEED NOT APPLY”, when a West Indian nurse had to pick the bus seat where she was “least likely to get hassled”, when homophobic views about “Nancy-boys” could be aired openly at Epsom Country Club. Then again, maybe Mitchell is holding a mirror up to the problems evident in our own little Brexitland?

Mitchell’s 562-page novel (a novel equivalent of a double album, perhaps?) is filled with sparkling dialogue and has stimulating things to say about creativity, mental health, the effects of domestic violence, the Vietnam War, grief, parental responsibility and what it was perhaps like to be an independent-minded female musician back in the day.

Above all, Mitchell pulls off this bold attempt at a novel exploring the undefinable mysteries of music and why music has such an impact on people. Jasper is pressed to say what the future will bring. “In fifty years, or five hundred or five thousand, music will still do to people what it does to us now. That’s my prediction.” Hear, hear.

‘Utopia Avenue’ by David Mitchell is published by Hodder & Stoughton on 14 July, £20

Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe by Richard Holloway ★★★★☆

The late singer John Prine’s satirical song “Jesus: The Missing Years”, about the period he disappeared from the scriptures as a teenager only to resurface at around 30, came to mind while reading Richard Holloway’s engrossing Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe. According to Holloway, the former Bishop of Edinburgh, “It seems likely that Jesus spent most of his life labouring on a building site.” Prine could have had a whole new verse for his song.

Holloway’s thought-provoking book includes stimulating observations on subjects as diverse as the injustice of the Windrush scandal, the problems of faith in a world that gave rise to Auschwitz, the beliefs of William Blake and the plight of factory-farmed turkeys.

Holloway, the engaging author of the bestseller Waiting for the Last Bus, was born in 1933, the year Hitler became chancellor of Germany. Holloway has seen his fair share of the suffering and punishment he writes about, including the time he witnessed the aftermath of the brutal death squads in El Salvador in 1980, during a fact-finding mission for Christian Aid.

The former primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church warns against people who “snort with contempt” at biblical stories. Full disclosure, I’m not a believer – pretty much an atheist in the Kurt Vonnegut vein of “why argue somebody else out of the expectation of some sort of Afterlife?” – but I warmed to Holloway’s willingness to confront faith’s uncertainty in “this fleeting world”.

Holloway says that “WH Auden’s ‘a haunted wood’ is a good metaphor for the universe” and his book is full of gigantic topics to chew over: life, death and the creation of a universe that contains around 140 billion galaxies (just the visible ones). He offers Bill Bryson’s tip to help get your head round that unimaginable number – that if galaxies were frozen peas, there would be enough of them to fill the Royal Albert Hall.

You may not find the answers you are looking for in this book, but Stories We Tell Ourselves is a sane guide through the turbulence of the modern world, one written with humour and self-deprecating pessimism. As Holloway puts it: “We find it painful to accept that the human condition is a rolling crisis we can learn to manage wisely but from which we can never escape.”

‘Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe’ by Richard Holloway is published by Canongate on 16 July, £16.99

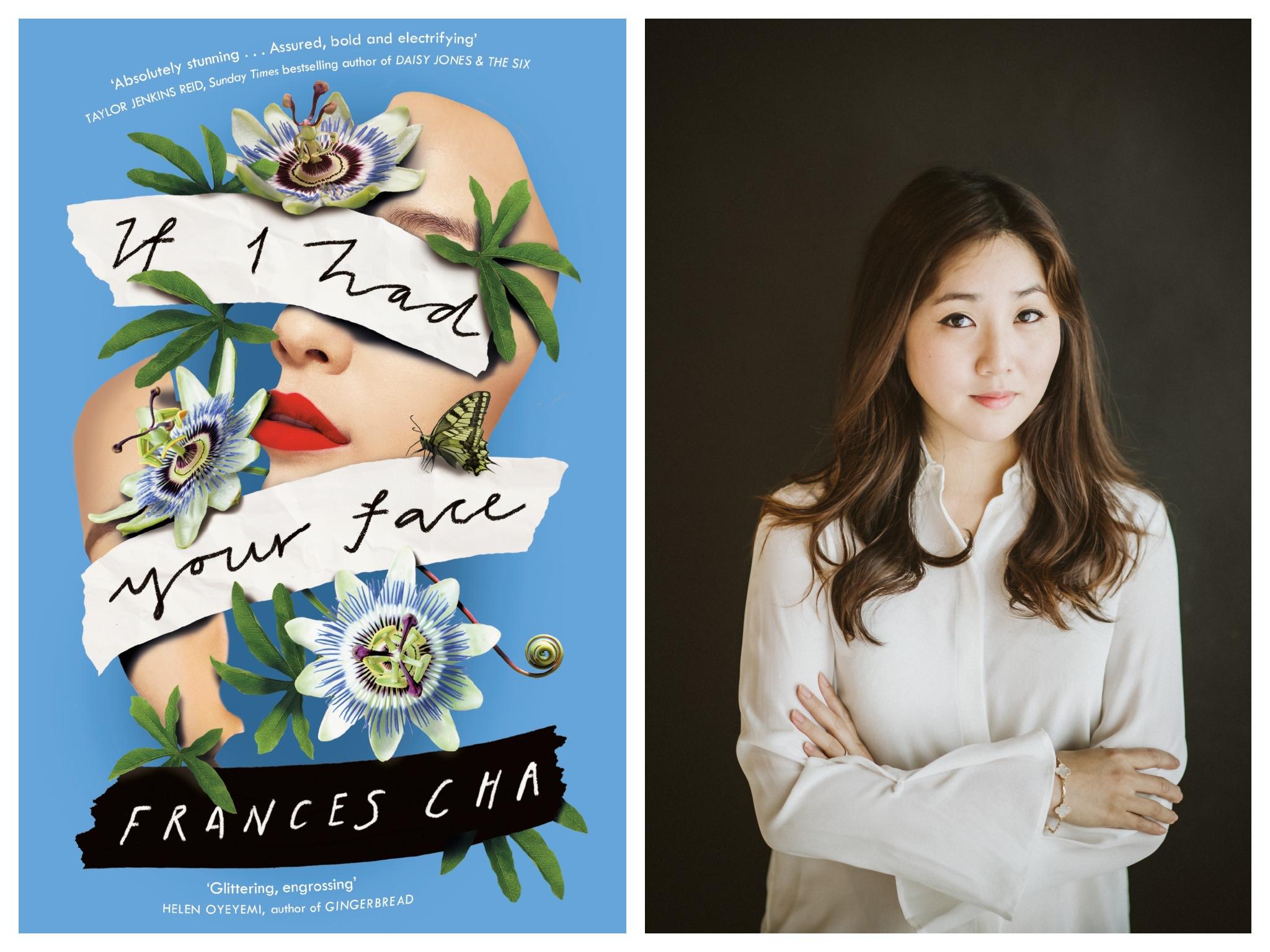

If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha ★★★☆☆

Frances Cha picked a grimly fascinating subject for her debut novel: the very in-your-face cosmetic surgery industry of South Korea and the very underground “room salon” culture – and the ways they are troublingly intertwined.

Cha, a former culture editor for CNN in Seoul, explores the truth behind the scenes in modern-day South Korea through the gripping story of four struggling women – room salon worker Kyuri, artist Miho, hair stylist Ara and pregnant housewife Wonna – whose lives collide.

Seoul is the world’s plastic surgery capital, where more than a million procedures take place a year at the “pretty factories”, everything from eye re-stitching to armpit whitening. Many of the patients are young teenage girls. A common operation is jaw reduction. Even the “lucky” patients face a post-operation year struggling with teeth that won’t align, their chins often so numb that they use their mobile phone cameras just to check if they are dribbling their food. In the worst cases, women have died from the flecks of jaw bone that get lodged in arteries. Cha shows this hideous business through the experiences of Kyuri’s friend Sujin.

Kyuri works at a room salon that is typical of the thousands that exist, places where sex work is carried out with little scrutiny, sometimes by under-age girls. Cha calls them “underground worlds where men pay to act like bloated kings”. These are places ruled by sadistic madams and pimps, supported by moneylenders who get their hooks into girls by advancing down-payments for surgery. Kyuri has little sympathy for the wives of the men who use her services, incidentally, raging at the naivety of these “clueless bats”, adding, “What, exactly, do they think their men do between the hours of 8pm and midnight every weekend?”

Like the film Parasite, If I Had Your Face is also an expose of the class system in South Korea. Cha’s novel is stronger on story than style, but it is a compelling tale. The novel is a relentlessly bleak presentation of South Korea, a land of rising unemployment, riven with misogyny and ageism, where women over 40 are “rendered entirely invisible in the eyes of Korean men of every generation”.

It was reported this year that South Korea’s female suicide rate is higher than in any other country on the globe. Cha’s eye-opening novel helps to explain why a generation of that country’s women are in such despair.

‘If I Had Your Face’ by Frances Cha is published on 23 July by Viking, £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments