Julie Christie is one of the shining lights of the silver screen – so why is she so overlooked?

Ahead of the rerelease of 1983 drama ‘Heat and Dust’, Geoffrey Macnab looks at how the Oscar-winning actor slipped through the cracks of Hollywood appreciation

It’s strange that the 80th birthday of Julie Christie last month passed with so little fanfare. While her contemporaries like Judi Dench, Charlotte Rampling, and Maggie Smith still appear on magazine covers and are written about regularly in the press, nobody pays much attention to Christie. If Michael Caine narrates documentaries about the Swinging Sixties or tributes are paid to directors Christie has worked with like David Lean, Joseph Losey, Sally Potter or Robert Altman, she is either left out altogether or mentioned in the most cursory fashion. It somehow seems to have been overlooked that she is one of the biggest stars that British cinema has produced in the past 50 years.

There are plenty of anecdotes about passers-by in Manhattan suddenly catching a glimpse of Greta Garbo crossing the road, walking in Central Park or shopping for groceries after the legendary Swede retired from the screen. Garbo was living anonymously in New York. She had the same aversion to publicity as Christie but she was still spotted regularly.

Unlike Garbo, Christie hasn’t retired. Her screen career had already slowed down by the 1990s when that of Dench took off. Since then, she hasn’t appeared in Bond films, done comedies set in far-flung hotels, or played dotty dowager duchesses in country house dramas. She may now be what The New York Times described as “a reluctant actress”, but she is still working and won multiple awards for her performance as the wife with Alzheimer’s, losing her memory and her identity, in Sarah Polley’s Away from Her (2007). She also recently narrated Isabel Coixet’s satirical drama The Bookshop (2018).

However, whenever Christie is prised back out into the light, you still feel that she is hiding in plain sight.

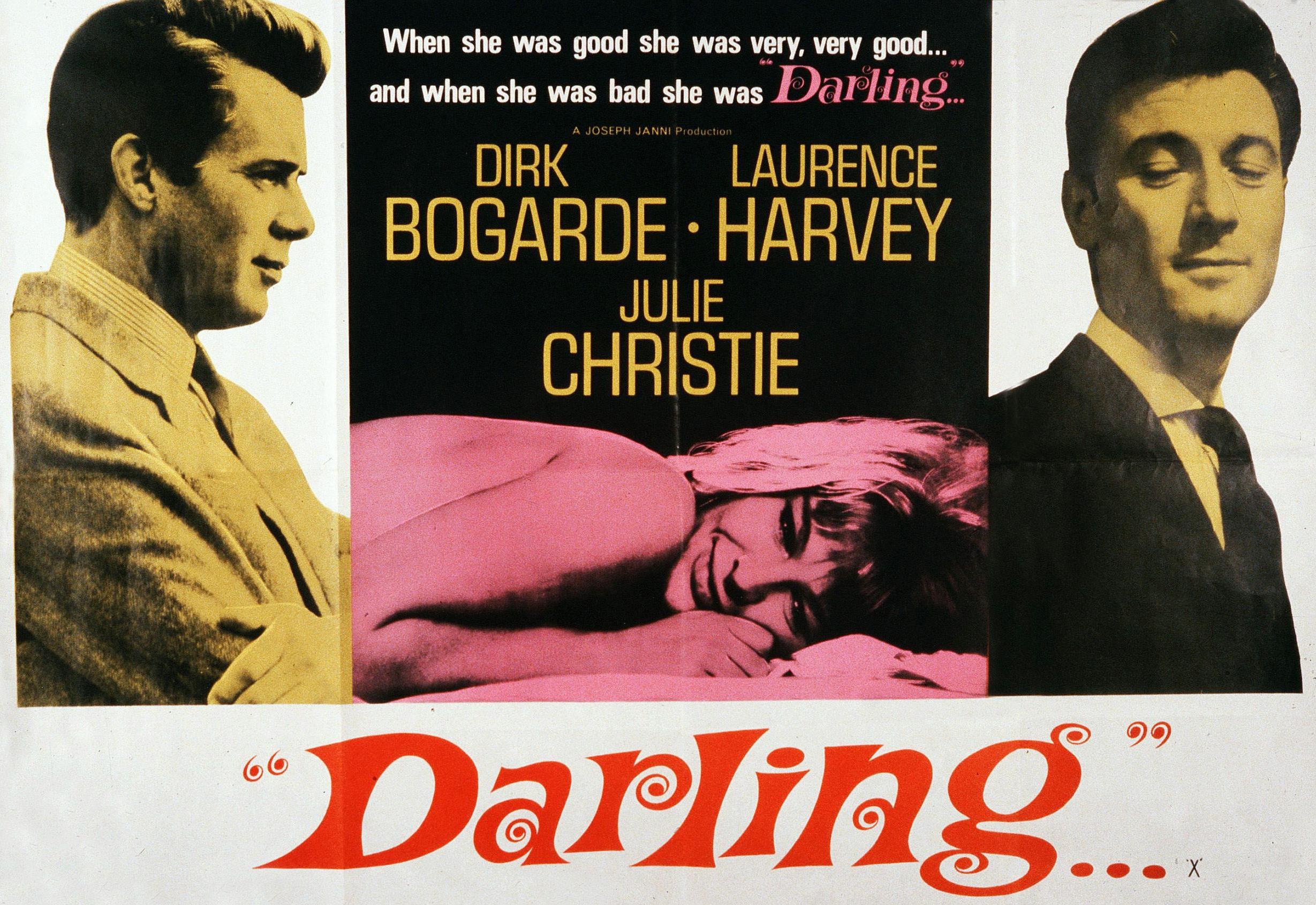

While other actors embrace their celebrity, Christie’s career is an exercise in distancing herself from it. She has spoken of “her absolute terror” at hearing her name pronounced in public and of the “pointlessness” of talking about herself. However, she has been remarkably astute in her choice of roles. Christie’s best-known features are acknowledged classics, revived frequently: Billy Liar (1963); Darling (1965), for which she won an Oscar in her mid-twenties; Dr Zhivago (1965); Far From The Madding Crowd (1967); McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971); and Don’t Look Now (1973).

A restored version of the Merchant-Ivory film Heat and Dust (1983), in which Christie co-stars, is rereleased this week but, typically, she is barely mentioned in the publicity material.

It is intriguing to watch one of Christie’s only TV interviews, given in 1988. Her dapper interviewer Michael Aspel is desperate to talk about her Hollywood career and private life but Christie wants to discuss Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge and the danger of another “holocaust” in Kampuchea. In return, she throws Aspel a few anecdotes about the making of Dr Zhivago and her baking activities at home in Wales. Then, unwisely, Aspel asks if she is worried about ageing. “I tell you what bothers me. It is people asking if the thought of the ageing process bothers me,” she replies testily.

Her irritation is obvious. Nonetheless, she looks as poised and glamorous as any other movie star guest on a talk show. There is no sense of stage fright. She just doesn’t want to deal with the inanity of celebrity culture.

“Come along my dear, brains, and beauty first,” a chauvinistic boss beckons Christie in an episode of A for Andromeda (1961), the BBC sci-fi series in which she had her first major role. She plays a lab assistant at the London School of Electronics who dies and is reconfigured as an android by a sinister computer. It isn’t the most subtle performance. She speaks in a monotone voice and stares blankly ahead, never blinking. Nonetheless, critics noticing her strikingly blonde hair and piercing gaze immediately likened her to an “English Brigitte Bardot”.

As Michael Feeney Callan’s biography of Christie reveals, she was soon after nearly cast as Honey Ryder, the female lead in the first Bond movie, Dr No (1962). Director Terence Young described her as “an absolute knockout”. Producer Cubby Broccoli, though, felt she wasn’t voluptuous enough and the role went to Ursula Andress instead. It was a lucky escape. Being one of the first “Bond girls” would have overshadowed everything she did subsequently.

Stardom came via a much more circuitous route. John Schlesinger had originally rejected her for the role of the mysterious, carefree Liz in the Bradford-set Billy Liar (1963). Topsy Jane was cast instead but she became ill during production. Christie was drafted in. She had just over ten minutes of screen time but made an indelible impression. First seen skipping down the streets, swinging her handbag, her tousled hair blowing in the breeze, she was an utterly free spirit, scruffy, bright and irrepressible. It wasn’t just Tom Courtenay’s Billy who was enraptured. So was Schlesinger – “by God, we have a star!” he supposedly exclaimed after watching the rushes in the cutting room.

“It was because she wasn’t much of an actress that she seemed to be a different sort of a girl,” screenwriter Frederic Raphael said later of her subsequent, Oscar-winning performance in Schlesinger’s Darling (1965), which he scripted. The remark may sound dismissive and patronising but Raphael was trying to explain her appeal to audiences. Unlike other British screen actors of her era, she was down to earth. She didn’t have hang-ups about sex or class. Nor, in spite of her striking looks, was she arrogant. Feeney Callan’s biography reports that Omar Sharif took exception to her eating habits during the shooting of Dr Zhivago. “She’d eat fried egg sandwiches for elevenses, which for me is totally unromantic,” Sharif grumbled about Lara’s diet.

Darling combined British social realism with Felliniesque satire. Christie was playing a glamorous, headstrong but vulnerable model whose pursuit of pleasure and fame ultimately brings misery. “She was not keen to be a star. She resented being beautiful because somebody at drama school had told her she would never have any trouble because she was so beautiful. Like many beautiful people, she had more doubt that confidence,” Raphael said.

The film transformed Christie into the “it girl” of Sixties British cinema. US magazine Look, on whose cover she appeared, reported that in London, you could see “hundreds of Julie Christie Darlings dancing the latest at the discotheques, fingering antiques in the Portobello Road, queuing up at Covent Garden for Fonteyn and Nureyev”. Christie hated the attention. The rest of her career can be seen as an attempt to escape it. What she continued to embody, though, was her generation’s independent spirit and distrust of authority.

“Anyone who grew up, as I did, during or just after the Second World War, must have wondered how they would have behaved if the country had ever been occupied. Would they have been part of the resistance, or a collaborator, or just tried to keep their head down?” Christie asked in her foreword to Common Ground, a 2006 book about the women of Greenham Common campaigning against nuclear weapons being placed in an RAF base in Berkshire.

Christie is firmly on the side of the resistance. She may keep her head down when journalists and paparazzi are in the vicinity but is very public in the support of causes she believed in. She considered her initial success a fluke. “A random combination of the good luck to work with a director like John Schlesinger and being considered very pretty had suddenly made me famous,” she wrote in a 2007 essay. Her way of coping was to become ultra-selective about what films she did and to make sure they reflected her social and political beliefs.

It’s revealing to watch her first appearance in the comedy Heaven Can Wait (1978), one of her films with Warren Beatty. This is as close as she came to a popcorn movie but, even here, she is a woman with a cause. She is first seen brandishing a petition, protesting about a proposed oil refinery that will poison the locals. Looking on, Beatty is instantly smitten by her sheer earnestness.

In Heat and Dust, she plays Anne, a former BBC researcher who heads to India to find out what happened to her great-aunt Olivia (Greta Scacchi) who, in the 1920s in the period of the Raj, had an affair with the Nawab of Khatmn (Shashi Kapoor). Anne’s experiences in the 1980s mirror those of Olivia’s 60 years before. Christie, who spent her early childhood in India, plays her role with resilience, tenderness and humour.

The qualities that make Christie so striking in her best screen roles are precisely those that led her to struggle with the concept of stardom. She is unaffected and natural. Whether she is Lara, the romantic heroine swept up in the turmoil of the Russian Revolution in Dr Zhivago, or Bathsheba, the “wilful, passionate girl” in Schlesinger’s adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd, there is no mannerism.

In her films with Beatty, she also shows plenty of comic brio. As the rough and ready cockney brothel madam in Altman’s western, McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971), she sounds like Eliza Doolittle. “D’you have anythin’ to eat. I am bloody starvin’,” she barks at McCabe (Beatty) when she first arrives in the muddy frontier town where he is trying to make his fortune. By contrast, in satirical sex comedy Shampoo (1975), she is at her most svelte and subversive. She plays Jackie Shawn, one of the many lovers of the wildly promiscuous hairdresser portrayed by Beatty. At one point, they make out on the bathroom floor. In another, comically outrageous scene, she goes under the table to perform oral sex on him in the middle of a political dinner.

“She is not only an actress. She is – in the high-class hooker terms of her role – the sexiest woman in movies right now…she’s a gorgeous, wh**y-tipped tipped little beast, a dirty sprite,” The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael enthused of a performance which shattered any sense that Christie was coy or prudish on screen. Other critics marvelled at her searing grief and shock as the mother who has just discovered that her child has drowned in Nic Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973). The film was also famous for the frankness and intimacy of the scene in which she and her husband (Donald Sutherland) make love. In 2014, Esquire called this “the sexiest scene ever”.

It may seem perverse to complain that Christie’s career is under-celebrated when she has gone to such lengths to stay out of sight. Nonetheless, as she turns 80, the prodigious achievements of Britain’s most reluctant but adventurous movie star surely deserve at least some acknowledgement.

‘Heat and Dust’ is rereleased on Vod on 15 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments