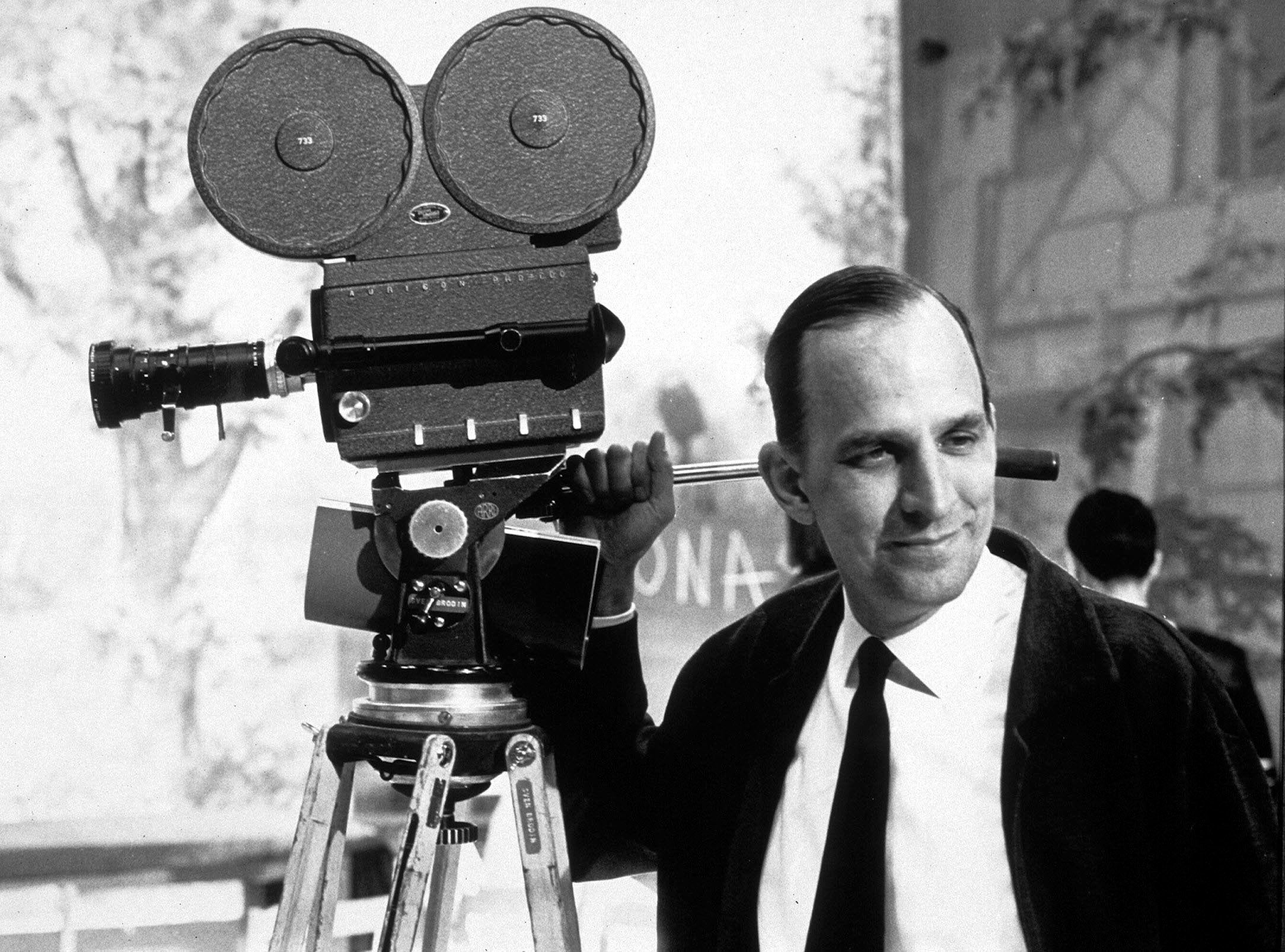

Bleak, beyond belief: Why we still love Ingmar Bergman films

With the 60th anniversary of the UK release of Bergman’s ‘Through a Glass Darkly’, the first in the Swedish director’s Faith Trilogy, Geoffrey Macnab looks at why these depressing films have endured, when most blockbusters from the same era have long since been forgotten

They are gloomy and angsty – about madness, sexual betrayal, existential despair, and incest. So why is Ingmar Bergman’s early 1960s Faith Trilogy, including Through a Glass Darkly – which was released in the UK and internationally 60 years ago – still holding us in its grip? If you want to understand why Swedish director Bergman’s trilogy feels so relevant today, watch the scenes in Winter Light (1963) in which a distraught-looking Max von Sydow is shown wrestling with the metaphysical monstrosity of existence.

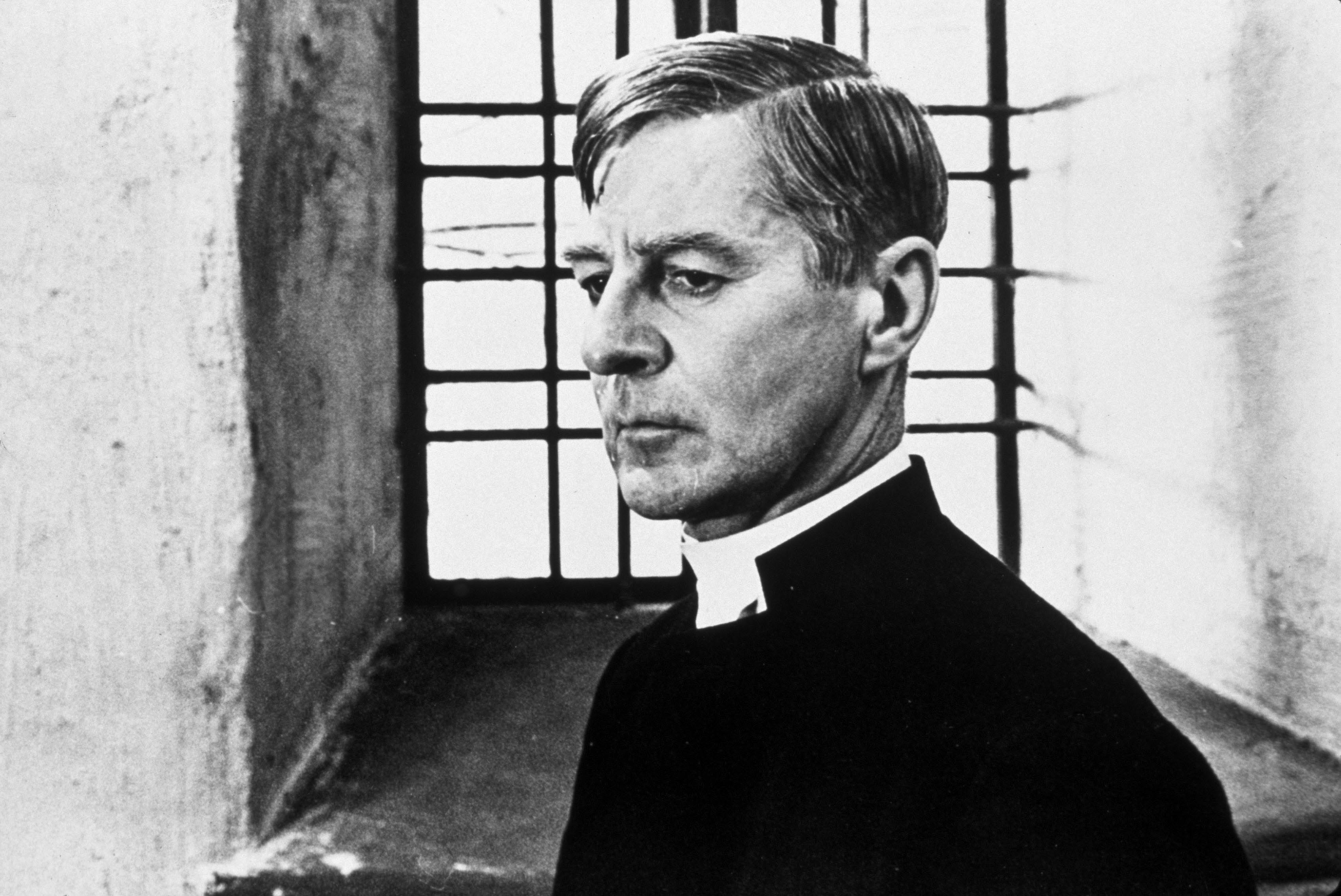

Von Sydow, one of Bergman’s favourite actors, plays Jonas Persson, seemingly a very ordinary and well-adjusted Swedish fisherman. Jonas is happily married with three children and “another on the way”. His wife is “a good woman”. He is in good health. Nonetheless, despair is eating away at him. He is near suicidal, afflicted with a strange abstract dread about the world that comes from reading far too many newspapers. He may not have Tory tax cuts, rising energy bills, a sinking pound, or a threat of nukes from Putin to worry about, but he is terrified that China, which he regards as a rogue state with nothing left to lose, might drop an atomic bomb.

“Why do we have to keep on living?” Jonas suddenly blurts out to the pastor (Gunnar Bjornstrand). The pastor struggles to give him a satisfactory answer.

Winter Light was the second in the trilogy after Through a Glass Darkly (1961) and before The Silence (1963). These were the films that consolidated Bergman’s reputation as the supreme purveyor of heavyweight Scandinavian angst and gloom. True, he had shown Death playing chess with a medieval knight, also played by von Sydow, in The Seventh Seal (1957) but that was almost a romp by comparison with the suffering shown in these three later films.

Why would anyone want to watch black and white movies about pipe-smoking Swedes enduring mental illness, religious doubt, and sexual neurosis? It turned out that they were subjects with which audiences had a morbid fascination. Sixty years later, the films still seem topical. They appeal both to audiences’ masochism and to their desire to engage with big questions about life, death, and what it all means.

Through a Glass Darkly won one Oscar and was nominated for another. Winter Light may have been dubbed “boring” by some critics but that didn’t stop it from being acclaimed as a masterpiece by many others. Bergman’s wife at the time, the Estonian concert pianist Käbi Laretei, actually described it as “a boring masterpiece”, as if it could be both at the same time. The Silence was one of Bergman’s most experimental and offbeat dramas but was a big commercial success – the graphic sex scenes helped.

“These three films deal with reduction. Through a Glass Darkly – conquered certainty. Winter Light – penetrated certainty. The Silence – God’s silence – the negative imprint. Therefore, they constitute a trilogy,” the director wrote cryptically in his screenplay notes. Later, he backtracked, denying that the pictures constituted a trilogy after all. By then, though, it was too late. They had already been bracketed together in audiences’ minds and it was impossible to separate them. Given that they featured many of the same actors, explored similar themes, and were made quickly one after the other, it is little surprise that critics and film historians have continued to connect them.

Through a Glass Darkly is about a widowed writer David (Bjornstrand) far more concerned with his work than his family. He hardly notices that his daughter Karin (Harriet Andersson) is suffering from serious mental illness. David hasn’t even read the letter sent to him by his son-in-law Martin (von Sydow) telling him that Karin has just had electric shock therapy. When he does discover how frail she has become, he writes notes in his diary, treating her condition as potential material for one of his books.

This was the first film that Bergman made on the remote Baltic Sea island, Fårö. He originally wanted to shoot in the Orkneys but the financiers wouldn’t let him. He went grudgingly but fell in love with the island at first sight, making six further films and coming there to live. He died on Fårö in the summer of 2007. With its craggy, rock-filled beaches, Fårö lends an extra layer of bleakness to an already dark film. Its four protagonists can hear the sound of the waves and a storm always seems to be on the horizon.

Karin is high-spirited but mentally very unstable. She is physically repelled by her husband but has a strange sexual attraction to her teenage brother. There is a strong autobiographical strain to the storytelling too. You can’t help but see elements of Bergman in the aloof, Prospero-like writer. It’s not a flattering self-portrait.

In an interview late in his life, Bergman, contemplating his various broken marriages, multiple affairs, and his difficult relationship with his children, admitted that he had been “family lazy”. For him, the work always came first. David in Through a Glass Darkly has exactly the same single-minded focus on his writing as Bergman had on his plays and films. The irony is that David is mediocre and superficial. He knows how to express himself and always chooses the right words. However, as his son-in-law (von Sydow) tells him, he is “a craven coward” who lacks ”common decency” and has no understanding of life itself. His “half-lies are so refined that they look like the truth”.

The film’s treatment of religious faith is deliberately ambiguous. In one strange scene, Karin has a manic episode. She prays, howls, and thinks she is seeing God through a door that is slowly opening, but all that she sees is a spider, which she imagines is attacking her. David has his moment of revelation in which he discovers that “love exists for real in the human world” and that this may be proof of God’s existence. Depending on your point of view, Through a Glass Darkly is either endorsing David’s faith or exposing him as a supremely hypocritical and deluded charlatan.

The other two films in the “trilogy” contain elements more commonly found in horror movies. You could easily imagine Winter Light re-imagined as an Exorcist-like drama about a priest possessed by Satan. It’s a murky film that, true to its title, is shot in a deliberately dark and overcast fashion. Tomas (Bjornstrand), the widowed pastor losing his faith, is a misogynistic figure. In one brutal scene, he berates Marta (Ingrid Thulin), the woman with whom he had an affair and who is still in love with him. “I’m sick of your myopia, your fumbling hands, your timidity. Your fussy endearments,” he tells her as she sits crying beside him. He talks contemptuously of her weak stomach, her bad skin, her periods and her chilblains. It’s a devastating attack. Everything about her disgusts him. He calls her “a hideous parody” of his late wife.

Tomas is selfish, spoilt, and fearful. He has lost his faith. Even so, Bergman shows him as a resilient figure who battles on and refuses to quit his pulpit. He is shown at the end of the film in his church, still ready to give communion to his tiny congregation. By putting their needs above his own, he finds some kind of redemption.

If Winter Light was Bergman at his most austere, The Silence showed the director at his most flamboyant. “I had decided to be uninhibitedly unchaste. It [The Silence] contains a cinematic sensuality that I still experience with delight,” the director wrote of his phantasmagoric story about two sisters, Ester (Ingrid Thulin) and Anna (Gunnel Lindblom), and Anna’s 10-year-old son. For reasons never explained, they travel by train to Timokla, an eastern European city preparing for war. They end up staying in a vast, near-empty hotel, which one guesses must have inspired Stanley Kubrick when he was adapting Stephen King’s The Shining. Among the few other guests are a troupe of performing dwarves.

The film has a warped, nightmarish feel. There is very little dialogue. The sisters don’t understand the language and are bitterly estranged. Ester is drinking too much and is very ill. Anna is on the prowl for sex. She hooks up with a waiter. As the adults behave in a decadent fashion, the little boy wanders the corridors of the hotel, spying on their antics.

Playboy gave the movie a thumbs up for having “the most explicitly erotic movie scenes on view this side of a stag smoker” even after it was cut for the US release. It was shown in New York in a cinema better known for ”striptease movies” – as The New York Times pointed out. The irony was obvious. This was the culmination of the director’s trilogy about religious faith and it was being treated as if it was a skin flick.

Seen today, The Silence feels eerily topical. With its imagery of refugees crowding the streets and the poignant image of the boy staring through a hotel window as a tank suddenly comes trundling round the corner, it evokes the sense of chaos and terror felt after the Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier this year.

The movies in the trilogy have never gone out of circulation. The enduring influence of Winter Light was shown when writer-director Paul Schrader drew heavily on it for his 2017 feature First Reformed, in which Ethan Hawke played a minister facing his own crisis of faith. Mia Hansen-Løve’s Bergman Island (2021) was shot on Fårö and owed a debt to Through a Glass Darkly.

It’s an unlikely achievement. Three depressing, modestly budgeted black-and-white, early-1960s Swedish features about spiritual yearning continue to be shown, and to inspire other directors, after most of the blockbusters from the same era have long since been forgotten.

The Faith Trilogy is available on BFI Player

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments