Infected Hollywood: Why filmmakers love disease

As coronavirus spreads across the world, Geoffrey Macnab looks at the rash of films about epidemics that all of a sudden are being given a patina of plausibility

When the world is in the grip of a pandemic, the last place you want to go and sit is in the middle row of the biggest, most packed auditorium at your local multiplex. This, you might think, is the optimum breeding ground for any self-respecting disease. Germs will be bouncing around in the foyer, through the air conditioning, off the popcorn tubs and into the fabric of the seats themselves. Every cough or splutter of another spectator will provoke mini paroxysms of anxiety.

It is little surprise, therefore, that, according to trade paper Variety, 70,0000 cinemas in China are currently closed amid reports of coronavirus infections all over the world. The planned Beijing leg of the publicity tour for the new James Bond film No Time to Die has already been cancelled, well in advance of the film’s April release. Hong Kong Filmart, one of the most important film industry events for bringing Asian and western producers and distributors together, has been postponed from its usual March date until August.

As the coronavirus continues to spread, this week’s Berlin Film Festival is carrying on but festival guests are all being given comprehensive information about procedures to follow if cases do occur and just how to find their way to the Berlin Institute for Virology.

The box office may be stuttering as the outbreak continues but the chaos is sparking the imagination of filmmakers and piquing the curiosity of some audiences. As The Independent reported recently, Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 thriller Contagion, in which Gwyneth Paltrow inadvertently brings a deadly Sars-like virus back from Hong Kong to the US, has been shooting back up the streaming charts in the weeks since COVID-19 hit the news. At the same time, news reporters have continually likened events in Wuhan, where the outbreak began, to those in zombie movies.

All of a sudden, films such as World War Z and 28 Days Later, which once seemed very far-fetched, are being given a patina of plausibility.

When Contagion first appeared in the UK, Soderbergh’s film received an unlikely seal of approval from health experts writing in the British Medical Journal. “Almost every year, Hollywood releases yet another blockbuster outbreak film with an entirely formulaic plotline. A highly lethal, usually flesh-eating, microbe is unleashed upon the planet. Its victims turn into zombies, and the human race turns against itself,” the BMJ experts complained about the usual, predictable rash of killer disease movies, but argued that Contagion was on a different level. “It’s one that finally gets the science right.”

Soderbergh may have got the science right but he wasn’t interested in making a public health movie. “I was trying to push it as far into a genre film as I could,” the filmmaker later told Film Comment. He wanted Contagion to reach audiences. This was a commercial, mainstream film on a subject that, like the disease it was about, crossed national boundaries and had a global reach. He had been working with screenwriter Scott Z Burns on a biopic of Nazi-era filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, but was worried that such a film wouldn’t find an audience. Therefore, when Burns told him he wanted to “make an ultra-realistic film about a pandemic”, Soderbergh immediately decided this was a very promising and bankable idea.

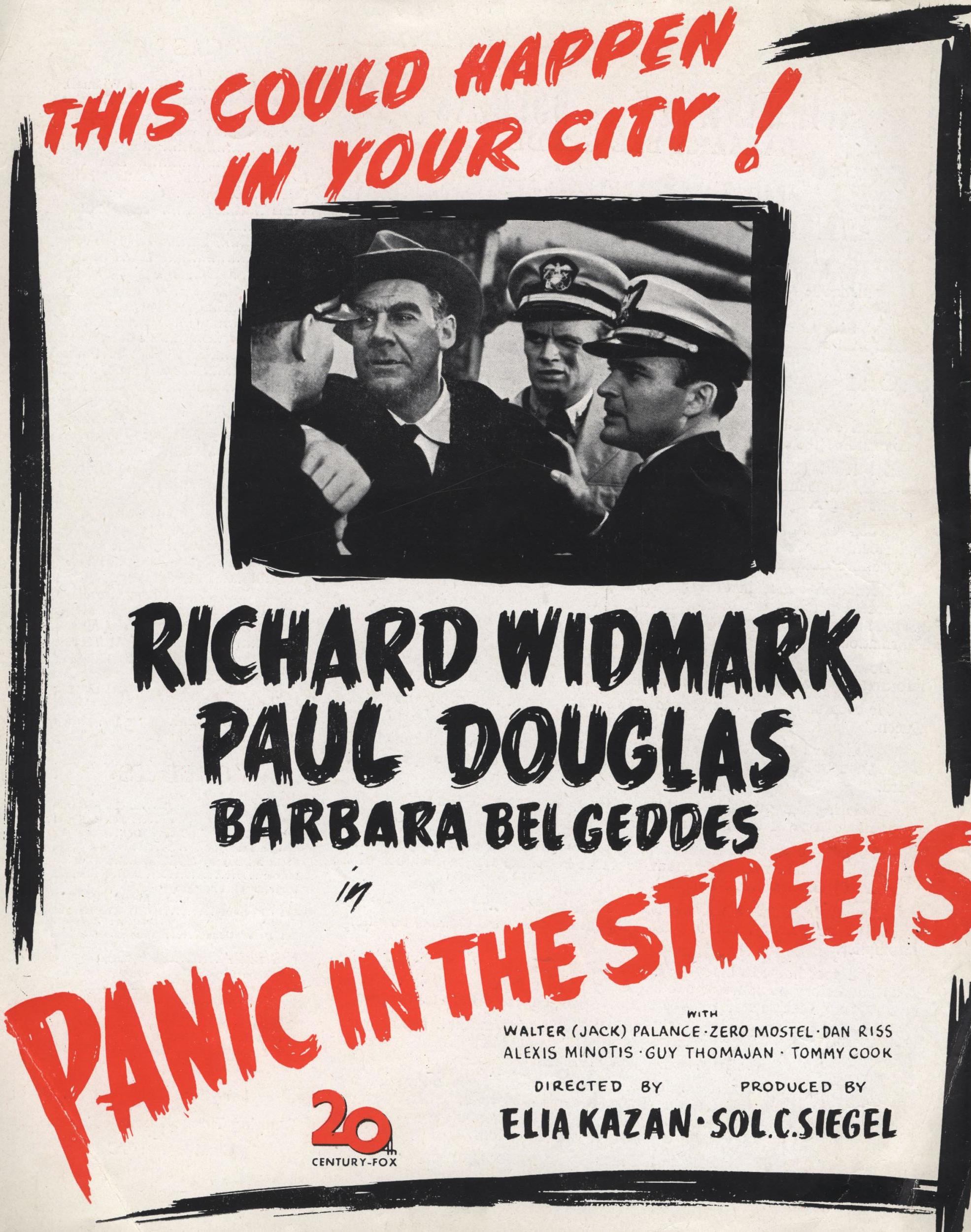

The director’s language chimes with that used by Elia Kazan when he was making his virus movie, Panic in The Streets (1950), in New Orleans. Ostensibly, the film was about a military health official, Lieutenant Commander “Clint” Reed (Richard Widmark), trying to stop the spread of pneumonic plague by tracking down anyone who had come into contact with a murdered illegal immigrant carrying the disease. Kazan, though, treated the story as a Third Man-like thriller.

The director was far more interested in shooting dramatic chase sequences in the streets, shipyards and warehouses of New Orleans than in exploring the health implications of the outbreak. He relished the chance to make the film on location, far away from the studios. In the film, Reed is in a race against time. If he doesn’t snuff out the disease within 48 hours, it will travel faster than the common cold. ”I’ve seen the disease work. If it gets loose, it will spread all over the country,” one character warns.

In Panic in the Streets, the potential outbreak of the plague becomes the equivalent of one of Hitchcock’s “MacGuffins”, a device that drives the plot but ultimately has little relevance in itself. The authorities could just as well be chasing thieves who’ve made off with gold bullion or Soviet spies who are holding radioactive material as in pursuit of germs.

“I hope that Outbreak is like the Jaws of the Nineties,” Wolfgang Petersen notoriously commented of his 1995 virus feature, made in the wake of Ebola outbreaks and with Dustin Hoffman cast, a little improbably, as the hardboiled army scientist trying to save humanity. Petersen was being honest but very flippant about why the movie was made. It was all to do with escapism and thrills, not with addressing public health hazards. Jaws was so successful that Universal set up an attraction featuring the Great White Shark in their studio theme park. Thankfully, Warner Bros haven’t done the same with Outbreak, although it too was a big box office hit.

As Hollywood was learning, viewers clearly liked films about illness and epidemics. Another Ebola-themed drama, series The Hot Zone, shown on National Geographic, achieved record ratings last year. Its producers, already planning a sequel, now have plenty more real-life material to draw on. Meanwhile, Netflix claimed huge viewing figures for its film Bird Box (2018), a grim, post-apocalyptic yarn in which some contagious and demonic force makes humans kill themselves in their millions.

It’s typical of filmmakers that they see opportunity rather than disaster in stories of contagion. They are drawn to disease both on a literal and in a metaphorical way.

“Film is a disease, Frank Capra said. When it infects your bloodstream, it takes over as the number one hormone. It plays Iago to your psyche,” Martin Scorsese declares at the beginning of his documentary, A Personal Journey through American Movies (1995), as if he felt all decent filmmakers were contaminated. “The antidote to film is more film.”

Movies about outbreaks of disease allow directors to switch between epic crowd scenes and eerie, intimate moments in which individuals realise that their bodies are betraying them. They can deal with lurking fears about everything from communists hiding in society to immigration and the fear of the “other”. Coronavirus symptoms can take weeks to appear after the initial infection. That detail evokes memories of the various adaptations of Invasion of the Body Snatchers in which replica humans are born from alien pods. They may look and talk normally enough but there is something not right about them. When it comes to disease in movies, the person sitting next to you on the train might have it. You might even be a carrier yourself, like the greyscale victims in Game of Thrones.

Alongside the disease disaster movies unashamedly trying to catch the multiplex audience, there have also been dramatic features, documentaries and TV dramas about HIV/Aids. These, though, have tended to be sombre and respectful affairs. While Ebola and Sars outbreaks inspire thrillers and exploitation movies, Aids is taken far more seriously by storytellers on screen.

Not every disease spawns movies. Sam Mendes’ First World War film 1917 is currently winning awards and performing strongly at the box office, but there have been very few films about the Spanish flu that broke out in 1918, at the end of the war. Many more people died as a result of this flu than perished in the trenches. The BBC recently broadcast docudrama The Flu That Killed 50 million, but filmmakers, in general, have stayed as far away as they can from the subject. It is considered just too grim, a story of complete failure. In the Hollywood disease disaster movies, some square-jawed scientist will usually find the antidote in time to rescue humanity before the final credits roll. In the case of Spanish flu, there was no hero on hand to save the day. Artists and filmmakers who found macabre poetry in the Somme or in Verdun struggled to come up with moving and evocative stories about the deadly flu and so they shunned it.

It is obviously far too soon to make coronavirus movies. Even the most opportunistic filmmakers will realise that it would be grossly insensitive to tackle the subject now, when the disease is still raging. However, when it is finally controlled, it can confidently be predicted that Hollywood will look for some way or other of turning the virus into the stuff of blockbusters.

‘Panic in the Streets’ screens at BFI Southbank as part of the Elia Kazan season on Saturday 22 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments