Cowboy with a killer phrase: the wild life and dazzling prose of Cormac McCarthy

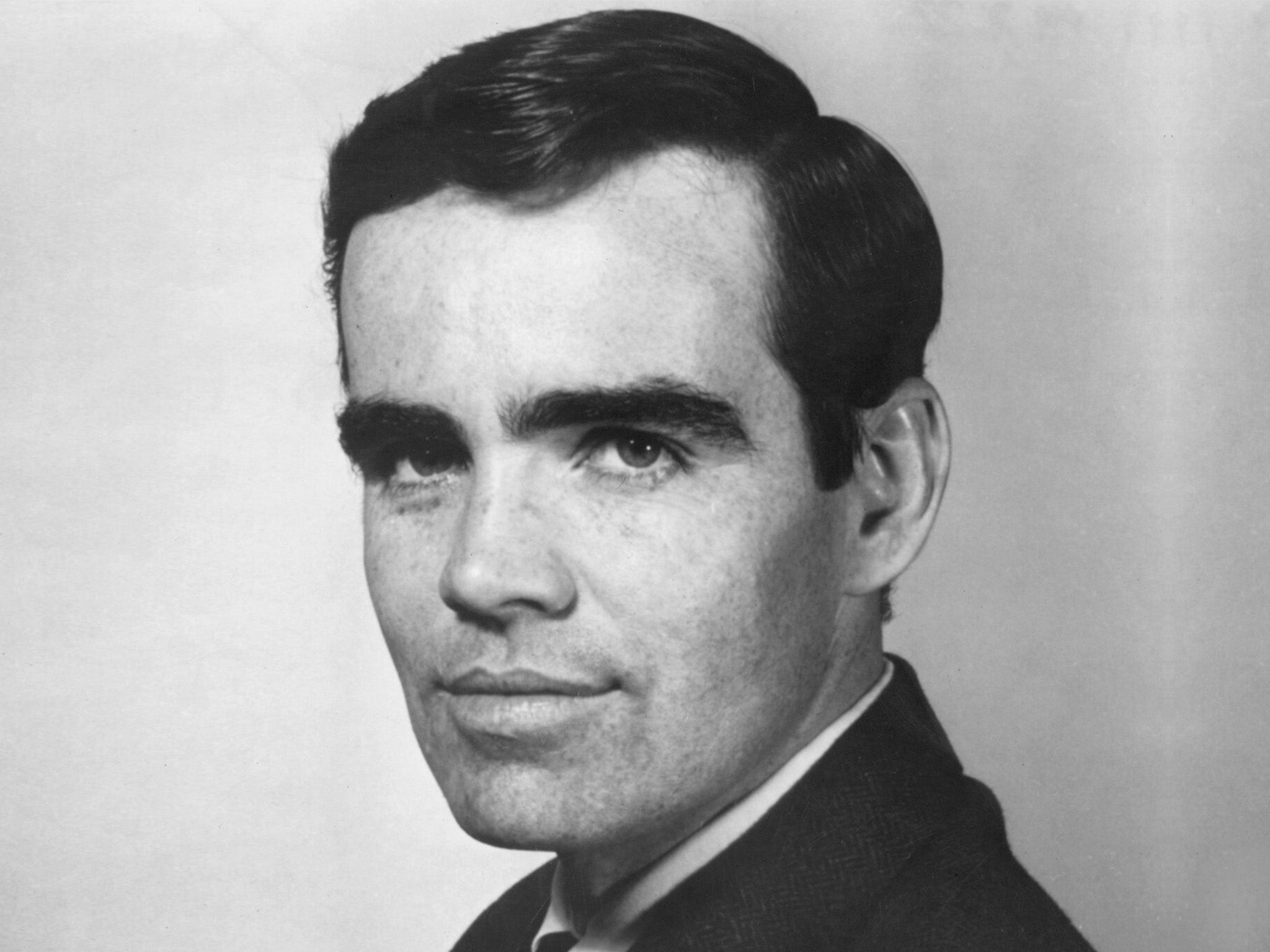

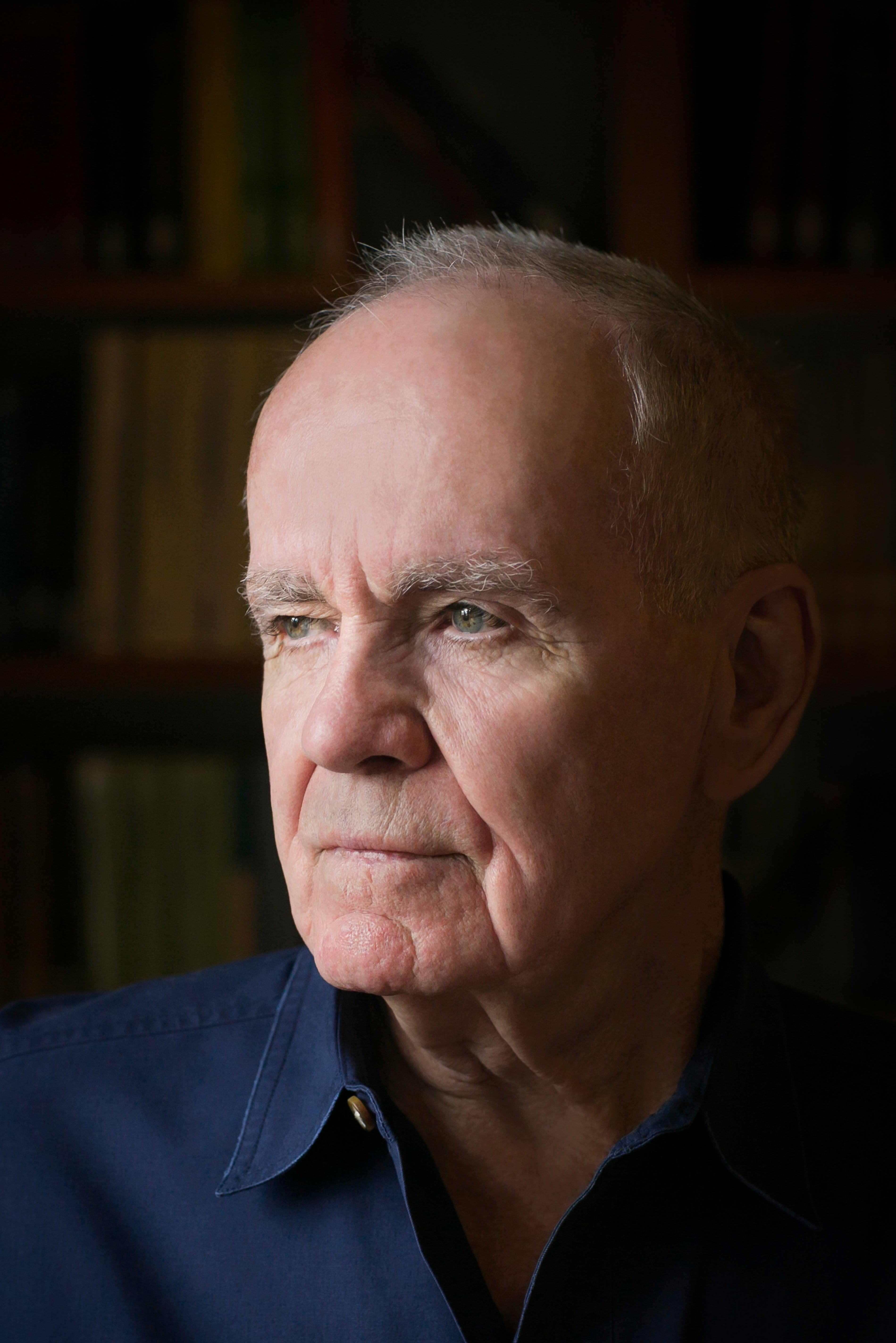

He gave few interviews, read ‘Moby Dick’ eight times a year, and overcame penury and heavy drinking to deliver 12 novels full of grit, beauty and violence. Martin Chilton remembers American novelist Cormac McCarthy, who has died at the age of 89

I can’t explain how one creates a novel,” Cormac McCarthy told Tennessee’s Kingsport Times in 1973. “It’s like jazz musicians. They create as they play.”

McCarthy, who died at his home in Santa Fe yesterday (13 June) at the age of 89, may not have been able to explain his genius, but his body of work – 12 novels including classics such as All the Pretty Horses, Blood Meridian, No Country for Old Men and The Road – are towering achievements that place him as one of the greatest authors of modern times.

Born on 20 July 1933, the eldest child of an eminent Rhode Island lawyer, McCarthy was christened Charles Jr – the Gaelic equivalent Cormac was bestowed on him by Irish aunts – and moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, as a child. “I hated school from the day I set foot in it,” he later remarked. After dropping out of education, he joined the US Air Force. Bored with barracks life in Alaska, he became a voracious reader, admitting, “I read a lot of books very quickly.” During a post-military career of odd-jobbing, including motor mechanic work in Chicago, he decided to write. His first novel, The Orchard Keeper, was published when he was 32, submitted on spec to Random House’s Albert Erskine, editor of William Faulkner.

The Orchard Keeper was a commercial flop and for the next few years, McCarthy – who divorced his first wife, poet Lee Hollerman after a year, leaving her with their son Cullen – struggled financially. He eked out a living as he tried to write books while living in a series of hovels in New Orleans (where he was thrown out of the French Quarter for nonpayment of rent), on the island of Ibiza and in east Tennessee. “I had no money, I mean none. I had run out of toothpaste and I was wondering what to do when I went to the mailbox and there was a free sample,” he told his friend Richard B Woodward in 2005. “Something would always turn up,” he added, echoing the blithe optimism of Dickens’s Micawber.

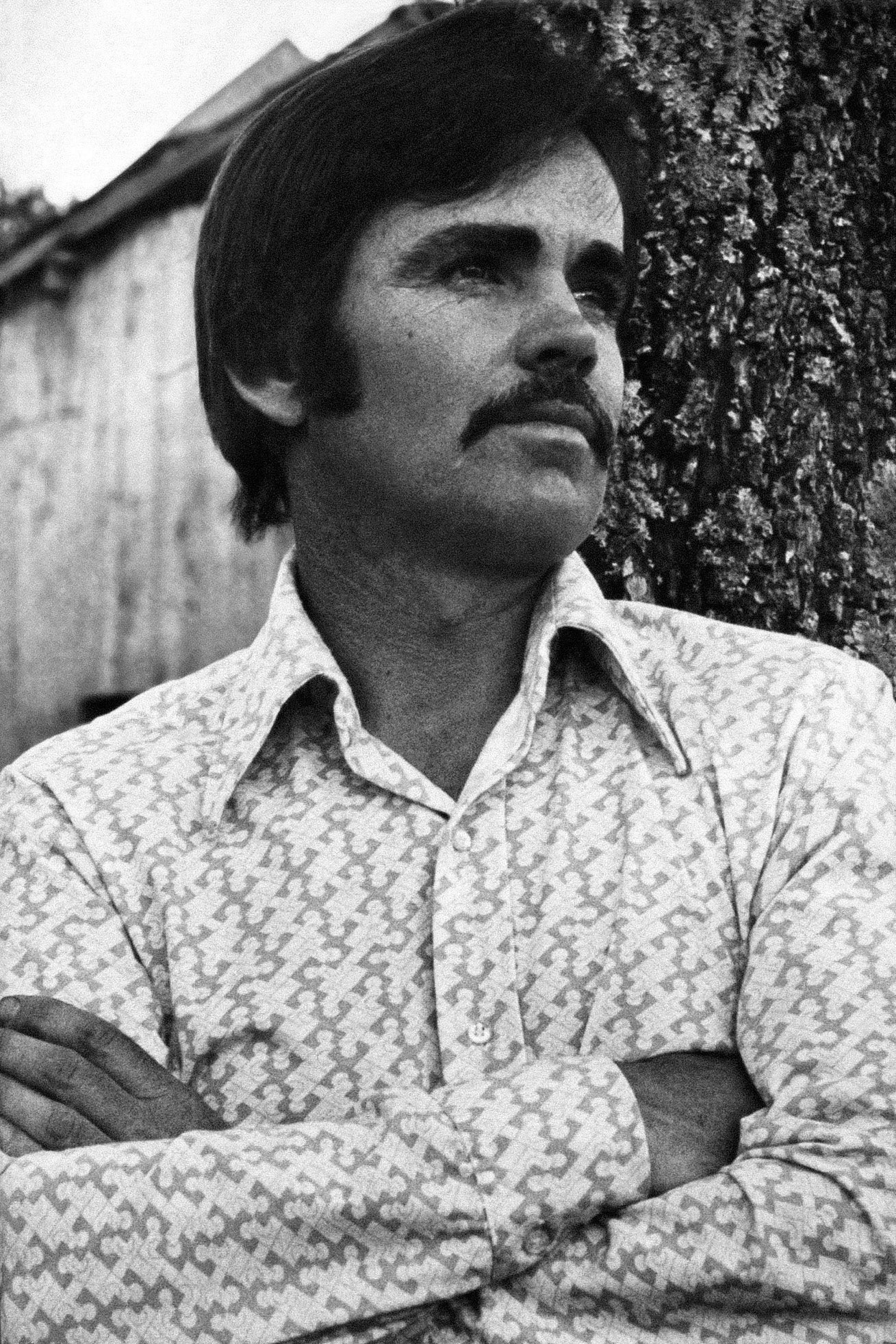

By the time he published Outer Dark in 1968, he had married again, to English singer Annie DeLisle. They lived near Louisville in a dilapidated dairy barn without electricity, with McCarthy repairing the dry-stone walls himself. Outer Dark achieved miserably poor sales, as did 1973’s Child of God, and McCarthy fell into drinking heavily, which he said was an “an occupational hazard to writing”.

“We lived in total poverty, we were bathing in the lake,” DeLisle told The New York Times in 1992, 11 years after she and the writer divorced. “Someone would call up and offer him $2,000 to come speak at a university about his books. And he would tell them that everything he had to say was there on the page. So, we would eat beans for another week.” McCarthy may not have enjoyed the penurious life but claimed he did not want to sell out. “Teaching writing is a hustle,” he remarked.

Child of God, which depicts the life of a serial killer in 1960s Appalachia, encapsulates some of the themes that most interested McCarthy. His characters are often outcasts, destitutes and criminals, scraping a living in the backwoods of east Tennessee or in the dry, vacant desert. The semi-autobiographical Suttree – published in 1979 – is easily his most humorous novel and it earned him considerable critical acclaim and literary grants to stave off poverty.

Blood Meridian, published in 1985, was his first true sales triumph, written with the help of a MacArthur Fellowship award. Saul Bellow, a member of the jury for this so-called “genius grant”, praised McCarthy’s “absolutely overpowering use of language, his life-giving and death-dealing sentences”. The novel is spectacular, a philosophic western about a gang of nihilistic killers that explores the nature of evil. McCarthy insisted on researching locations for his books and made dozens of scouting forays to Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and across the Rio Grande into Chihuahua, Sonora and Coahuila.

“I’ve always been interested in the Southwest,” McCarthy explained about his Border Trilogy. “There isn’t a place in the world you can go where they don’t know about cowboys and Indians and the myth of the West.” The three-book series comprised All the Pretty Horses (1992), The Crossing (1994) and Cities of the Pain (1998). I remember devouring All the Pretty Horses in one sitting; I firmly believe it is one of the essential postwar American novels. The protagonist is a teenager named John Grady Cole, who rides off to Mexico. The novel is dialogue-heavy and beguiling. Along with being an incredibly affecting rites-of-passage novel, it also contains magnificent writing about nature and horses.

By the time the Border Trilogy was completed, McCarthy, then living in El Paso, had married for a third and final time – to Jennifer Winkley, a woman three decades younger. Together they had a son called John, whom McCarthy described as “the best person I know, far better than I am”. He and Winkley divorced in 2006. A strange postscript: she turned up in the news in 2014, when she was arrested on suspicion of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

Although McCarthy was often presented as a recluse, this is an inaccurate image. Usually dressed in cowboy boots and jeans and a crisply pressed shirt, McCarthy had many friends outside the literary world, including high-stakes poker player Betty Carey. In 1994, an old friend of mine, writer Mick Brown, tracked McCarthy down to Luby’s family restaurant in El Paso to ask for an interview. “I’m sorry, son, but you’re asking me to do something I just can’t do. I’m just not in the writing business, you know? If I’d known all this was going to happen, I’m not sure I’d even have started,” he said, before turning back to his soup.

Yet he could be chatty and expansive when on the record. Between 1968 and 1980, he gave at least 10 interviews to local newspapers in Lexington, Kentucky, and east Tennessee. He was interviewed twice at length by Woodward, and in 2017 gave a 75-minute filmed interview to David Krakauer, the President of the Santa Fe Institute, a mountaintop retreat in New Mexico where McCarthy used to go to write. The video is on YouTube and shows a man who was jocular, open, erudite and witty.

“Smart people are fun to talk to,” said McCarthy, who also expounds on his love of mathematics in the video. It is a fairly hidden part of his career that he edited books for scientist friends, joking that he was “trying to get them to write better”. In 2012, he edited a book called Quantum Man. The author, Lawrence M Krauss, recalled his methods. “To start with he made me promise he could excise all exclamation points and semicolons, both of which he said have no place in literature.” McCarthy’s own style was spare and had minimal punctuation.

By then, the film adaptation of his 2005 western No Country for Old Men had made McCarthy a household name. The novel is about violence and people living in peril. McCarthy said he had known a few drug dealers (“some of them lovely, gracious people, very well educated”) and it had interested him to write about people who “know when they get up that morning that there’s some chance somebody’s going to get killed”. The novel was adapted into a film by directors Joel and Ethan Coen (Joel praised McCarthy for the way his “intense focus on place informed his stories”) and made a star of Javier Bardem for his portrayal of McCarthy’s psychopath villain, Anton Chigurh.

I read McCarthy’s 2006 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Road when my first son was about 10, the rough age of the unnamed boy who travels across a burned, ravaged and lawless America in this bleak masterpiece. Perhaps that is why I found this apocalyptic survival book so potent and scary, but it also struck a chord with millions of readers. It was made into a haunting film directed by John Hillcoat, with a screenplay by Joe Penhall. In 2010, Penhall gave a fascinating account to The Guardian of a boozy encounter with McCarthy, in which he revealed that the author talked a lot about John, “the treasured son who inspired so much of The Road”. McCarthy told Penhall that while Blood Meridian was about “the limits of our inhumanity”, The Road was about “the limits of our humanity”. McCarthy demonstrated his own canny way of providing for John’s future, incidentally, in signing 250 copies of The Road – the only copies he autographed – to leave to his son to sell as prized collectors’ editions.

I am not interested in sex books

It is worth noting that McCarthy’s own career as a screenwriter was far from sparkling. After writing the script for an undistinguished 1976 television drama called The Gardener’s Son, McCarthy delivered a rather dull screenplay for 2011’s The Sunset Limited, starring Samuel L Jackson and Tommy Lee Jones. Worse was to come in 2013, with Ridley Scott’s The Counsellor, also starring Bardem, alongside Michael Fassbender, Penelope Cruz. McCarthy’s screenplay prompted The Independent’s Adam White’s assessment that McCarthy “doesn’t really know how to write a Hollywood movie”.

McCarthy didn’t really write about love or domestic issues – “I am not interested in sex books,” he once said – and he admitted he was conscious of not having written female protagonists. This was something he put right in his final novel, Stella Maris, a coda to The Passenger, both atmospheric and pungent novels. They were among my pick of the 20 best books of 2022.

McCarthy’s books will remain essential reading because they deal so brilliantly with fundamental, burning questions of morality, and issues of life and death. His own favourite author, incidentally, was Herman Melville, and of the 7,000 books he kept in storage lockers, his most treasured was Moby Dick (he told British publisher Peter Straus he read the mammoth novel eight times a year), although he disdained Marcel Proust and Henry James. “I don’t understand them,” McCarthy said. “To me, that’s not literature. A lot of writers who are considered good, I consider strange.”

Stephen King mourned McCarthy’s death by describing him as “maybe the greatest American novelist of my time”, words that do not seem hyperbolic for such a dazzlingly talented writer and storyteller.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments