Claude Rains: Why he’s one of the greatest character actors ever

The ‘Casablanca’ and ‘The Invisible Man’ actor may not have cut it as the leading man but he often stole the show, says Geoffrey Macnab who looks back at his career on the centenary of his screen debut

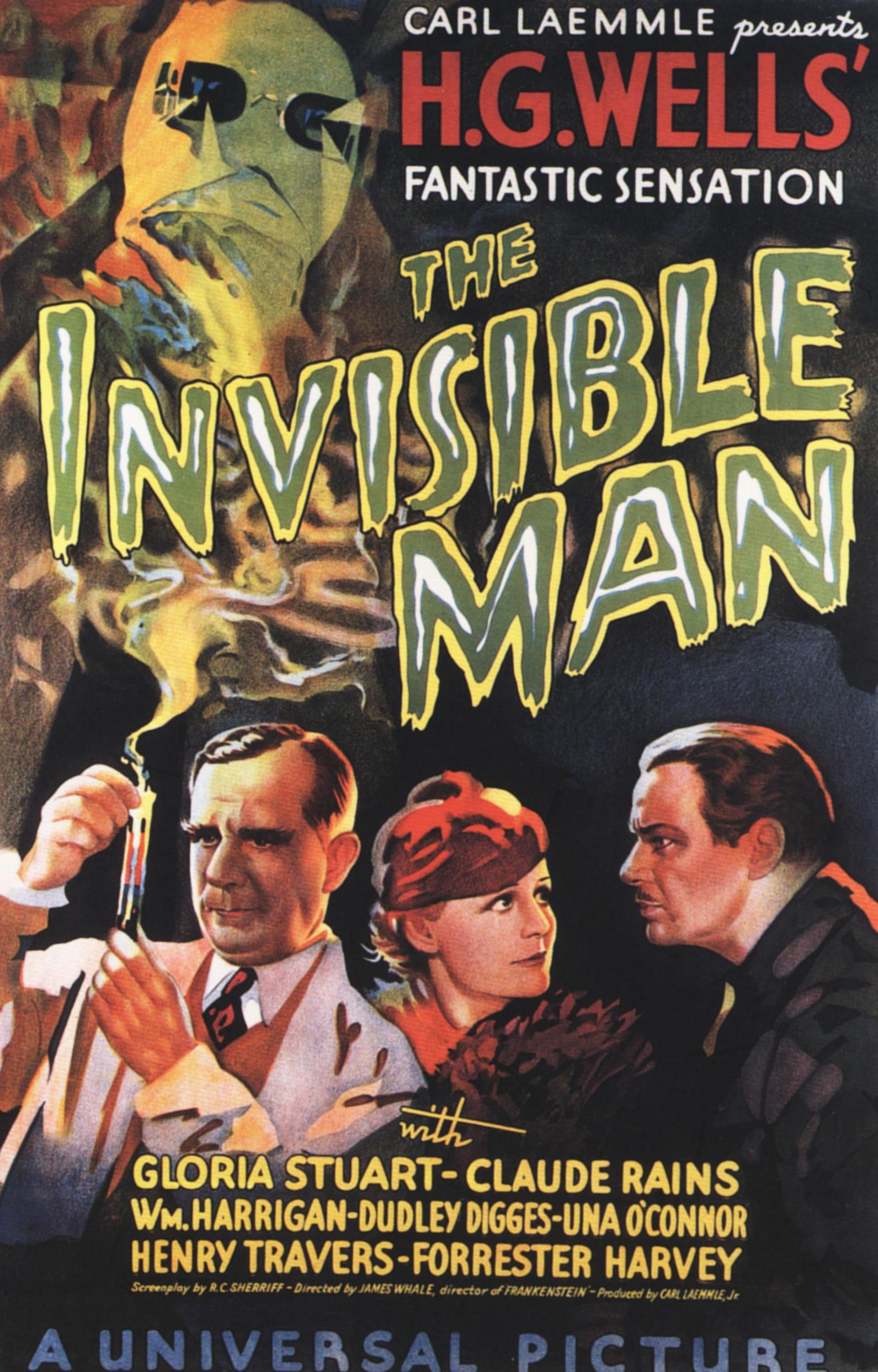

Claude Rains was very short. When he appeared in Notorious (1946), Alfred Hitchcock had to stand him on a box for some of his scenes with Ingrid Bergman. He became a movie star in his early forties with The Invisible Man (1933), in which the audience could only see his face for a few moments at the end. As a leading man, he didn’t really cut it. “You’re small aren’t you. I don’t think you could play heroes,” one of his early mentors, actor-manager Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, warned him. He had had a deprived and brutal south London childhood. “He grew up in the slums of London,” his daughter Jessica told the audience at a special screening of one of his films in 2012. “He was one of 12 children. All but three died from malnutrition when they were children. It was rough.”

His biographer David J Skal writes about his “wretched diction” and “air of waif-like vulnerability” as a kid. He was wounded, partially blinded, and almost killed in the trenches during the First World War. Married six times himself, he often played cuckolds and repressed and unhappy husbands. Nothing about his background was very grand and yet Rains (1889-1967) has a fair claim as one of the greatest screen character actors of all time.

Rains received four Oscar nominations – all in the Best Supporting Actor category. He combined brilliantly with Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca. Bette Davis described him as her favourite co-star. David Lean, an arch-perfectionist himself, marvelled at his technique and his meticulous approach.

No one could match Rains’s capacity for conveying yearning and sophisticated melancholy on screen. Other actors weren’t as dapper or as subtle, as fluent or as elegant. He had the knack of making the most hard-bitten villain seem perversely sympathetic. “Mr Rains’s low, husky voice, his power in investing even commonplace dialogue with smouldering conviction, is remarkable. He never rants but one is always aware of what a superb ranter he could be,” the novelist and former film critic Graham Greene wrote of him early in his screen career.

You can’t help but think that Greene borrowed from one of Rains’s early movies when writing one particular scene in The Third Man; it showed the racketeer Harry Lime (Orson Welles) looking down disdainfully from the Ferris wheel at the people scurrying below. “Fascinating, those insects – the so-called human race,” says Rains as the jaded, corrupt lawyer Lee Gentry in Crimes Without Passion (1934), as he stares from his high-rise office down at the streets. “They don’t look like murderers and wife-beaters from here.”

Poise is Rains’s defining characteristic. He may seem crestfallen when Ingrid Bergman chooses Cary Grant over him in Notorious, or smoulder with rage when his wife Ann Todd goes on a secret date with another man in The Passionate Friends (1949), but that doesn’t mean he is ever going to raise his voice. His daughter Jessica claimed that when she was growing up, she couldn’t “understand a word” of his cockney accent, but on screen, he is always perfectly spoken and very easy to comprehend.

The magic of Rains’s performance as the corrupt French officer Louis Renault in Casablanca comes from his sardonic, world-weary calm. At climactic moments, he can utter lines like “round up the usual suspects” without losing his self-possession. He has a fatalistic air – as if he expects everybody apart from his beloved Rick (Bogart) to behave in a venal and cowardly way and isn’t remotely surprised when they do so.

Nothing in Rains’s acting betrays effort or anxiety. However, as John Gielgud once said of him: “He was a self-made man who absolutely clawed his way into success by sheer willpower.”

Rains oversaw his own Pygmalion-like transformation from south London street urchin and occasional thief into dapper, worldly, stage and screen star. “Rains had turned a cockney boy with a speech impediment into an officer and gentleman,” Aljean Harmetz wrote about his metamorphosis in her book on the making of Casablanca.

He approached acting with a painstaking dedication akin to that of a virtuoso musician.

“Claude always amused me because he carried timing to an almost absurd degree,” said Lean, who directed him in The Passionate Friends. “You can almost put a Claude Rains scene to numbers.” At the same time, he didn’t take himself too seriously and escaped from Hollywood whenever he could to spend time as a country squire at his farm in Pennsylvania.

This year marks the centenary of Rains’s first screen appearance in his only silent movie, Build Thy House (1920). It was an earnest British drama about workers “seething with discontent”, as one review put it, at their wages and living conditions. He played the “drunken loafer” who recognises that the young man back from the war and passing himself off as the son of a recently deceased factory owner is an imposter. Trade paper The Bioscope has a still of the film showing Rains sitting in a corner in an open-necked shirt, looking moody. There was to be a 13-year hiatus before Rains appeared on screen again.

Rains knew the world of London theatreland inside out. He had started working backstage in the West End when he was 12 years old, running errands and taking on odd jobs. Eventually, he became a prompter and “call boy”. The summit of his ambition was to work as a stage manager, and, as he told Tree, “to live nice”. After he went through gruelling elocution lessons and worked on his posture to compensate for his diminutive size, his horizons broadened. He began to play small parts in Tree’s productions while continuing to do his backstage work.

After the First World War, Rains became a successful and prolific theatre actor. The critics loved him. Look through a random selection of reviews of West End stage productions in which he appeared in the 1920s, and you’ll find him singled out in almost every one. He was widely acclaimed for his role as an “opium-smoking wreck” in a 1921 production of Louis Vermeuil’s Daniel. Photos of the production show him looking very wan and decadent, in a long silk dressing down.

“Particularly fine” was the verdict on his performance as the philosopher and sniper David Peel in a 1923 production of John Drinkwater’s play Robert E Lee. “Cannot help acting with distinction,” one critic said of his performance as the “dope-taking, dram-drinking” Earl of Trenton in Good Luck, a very far-fetched stage drama featuring a car accident, a burning prison, a shipwreck (“complete with real water and a lifeboat”) and a horse race at Ascot.

Rains was “masterful” as the bank cashier turned robber in Georg Kaiser’s play From Morn to Midnight in 1926.

“Altogether admirable” was the verdict on his Napoleon – a rare leading role for which he had the right stature – in a 1924 production of George Bernard Shaw’s The Man of Destiny. Rains was judged to have captured not just Napoleon’s “tremendous personality” and genius but his “weakness for women, his selfishness and his ill-breeding”.

While giving all these formidable performances, Rains was also teaching acting at Rada, which had been founded by Tree. Among those Rains tutored were Charles Laughton, Gielgud, and Laurence Olivier.

As his stage career blossomed, Rains showed little interest in cinema. Even when he went to the US in the late 1920s with his then-wife Beatrice Thompson and established himself as a major talent on Broadway, he ignored Hollywood.

Rains won his breakthrough screen role in The Invisible Man in a roundabout fashion, mainly because the first choice Boris Karloff was in a contractual dispute with the Universal bosses. Director James Whale, who knew Rains from the London stage, liked his mellifluous voice. According to Skal, Whale was so worried about Rains’s “near-total unfamiliarity with film or film acting” that he put the actor on a strict regime of “three movies a day” so he could get up to speed on film technique.

Playing Dr Jack Griffin, the invisible man, was burdensome in the extreme. Rains had to act beneath multiple bandages. The film was heavily dependent on optical effects. Nonetheless, he brought humour and zest to the role. When he peels off the bandages and a slow-witted policeman realises there is nothing beneath them (“how can I handcuff a bloomin’ shirt”), Rains’s voice and wild gestures with his clothes convey his relish at the chaos he is causing.

The Invisible Man was a huge hit. In its wake, Rains was offered plenty more roles as madmen, drug addicts and killers. Only gradually did his full range become apparent. He had been known on stage as a “very showy actor”, as Gielgud once called him, but his greatest screen performances are marked by restraint. The Passionate Friends may not be one of Lean’s finest films but it shows Rains at his absolute peak. He plays the wealthy banker whose wife (Ann Todd) spurns him for an old boyfriend (Trevor Howard). Eric Ambler’s screenplay provides him with some strong lines (“You were my wife and you made me hate and despise myself”) but the real strength of his performance is in his expressions and mannerisms. We can read his jealousy and humiliation in his furtive expression as he spies on his cheating wife or in his look of despair when he spots unused theatre tickets and realises she has been lying to him.

When playing conventional leading roles, Rains sometimes seemed dull and out of place. He was cast as Julius Caesar opposite Vivien Leigh in big-budget British flop, Caesar and Cleopatra (1945), but, as one reviewer noted, his Caesar was more “nice old gentleman” than tragic romantic hero. By then in his late fifties, he was too old to pretend to be a matinee idol. Tree’s remark about him not being the type to play heroes was underlined. By contrast, in his films with Davis, as her psychiatrist in Now, Voyager, or as her long-suffering husband in Mr Skeffington, he is superb. With Davis, as with Bogart in Casablanca (“Louis, I think this the beginning of a beautiful friendship”), he is the perfect foil to the big-name star.

Rains was a paradoxical figure, someone who claimed his acting career happened by accident but who was a dedicated and consummate professional. He showed no interest in cinema and didn’t make his first Hollywood movie until later in life and yet still racked up close to 80 film and TV credits.

“You son of a bitch. You stole the picture,” Davis complained in mock fury to Rains after they appeared together in Deception (1946). That was a trick the British actor had been performing ever since he made his debut in Hollywood. Rains could be cast in supporting roles alongside the most beautiful and charismatic male and female leads in Hollywood history – but his performance was still often the one that lingered the longest in the audience’s memory.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments