Vaccine wars: The scramble for a pandemic panacea descends into chaos

The scramble to administer vaccines was meant to signal a turning point in the fight against the coronavirus, but has exposed global political tensions, reports Borzou Daragahi

The rollout of Covid-19 vaccines across the world was meant to alleviate the effects of a devastating pandemic and set the world back on a course towards normalcy.

But so far, at least, it’s spawned one crisis after another.

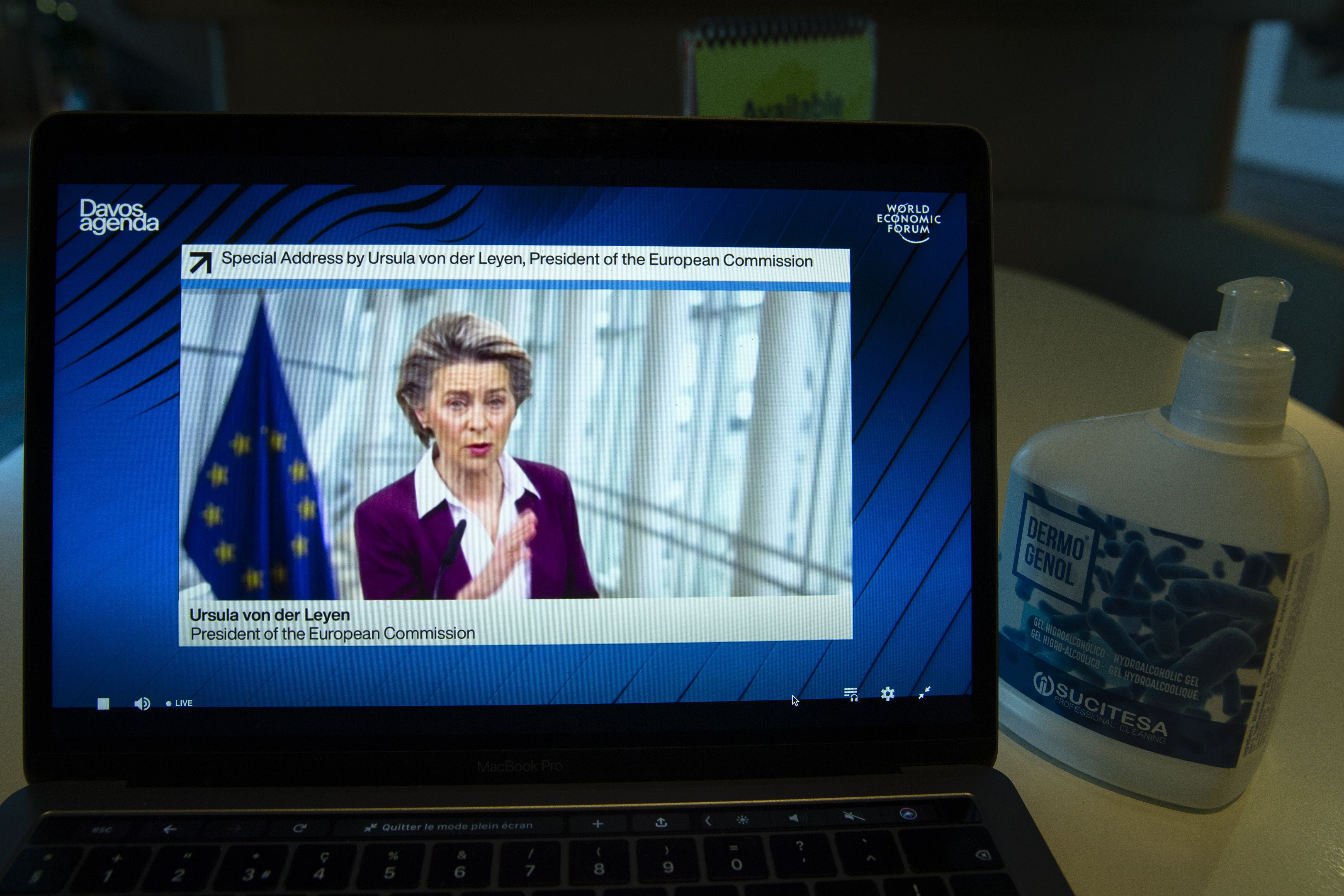

In Europe, officials in Brussels are publicly duking it out with the executives of AstraZeneca, the pharmaceutical firm, each blaming the other for the slow rollout of vaccines. The European Union was forced into an embarrassing climbdown after trying to enforce a vaccine border on Northern Ireland from the Republic, using a clause in the recently negotiated Brexit deal with the UK.

In Iran, the country’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, has injected his own ideological animosity towards the west into public health, barring the import of vaccines from the United Kingdom or the United States, and even rejecting donation of 150,000 doses of the coveted Pfizer vaccine.

In Germany, a newspaper has sparked a panic by apparently incorrectly reporting the efficacy of a vaccine on the elderly.

The swirling controversies over the introduction of the vaccine only raise public alarms and, increase what public health experts call “vaccine hesitancy,” a tendency among people to avoid inoculations.

“This virus loves it when people are bickering and politicking,” said Luke O’Neill, an immunologist at Trinity College in Dublin. “We are in the middle of an emergency and we need to keep confidence. Instead, people are very anxious and when they see the headlines they become even more anxious.”

There are 10 vaccines already being used around the world. Another 63 are being tested on humans and 173 tinkered with in labs. Taken together, they represent the best hope for stamping out a pandemic that has already killed 2.2 million worldwide, infected more than 100 million and caused massive economic damage.

But the chaotic introduction of inoculations across the world underscores the potential for a long hard slog ahead before the coronavirus crisis is over, and shows just how logistically challenging and politically fraught it will be to mass vaccinate the planet. Experts estimate it won’t be until the middle of 2023 before the entire world achieves a high level of immunity from coronavirus.

Many senior global health officials have been warning for months about what they call “vaccine nationalism”, in which countries across the world scheme against each other to hoard supplies of vaccine and inadvertently slow the halting of the disease.

“A ‘me first’ approach leaves the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people at risk,” the World Health Organisation director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesusn, said in a speech on Wednesday. “It is also self-defeating. These actions will only prolong the pandemic, the restrictions needed to contain it, and the human and economic suffering.”

But what appears to be happening is far more chaotic and difficult to pin down, but could end up amounting to eroding public trust in the vaccine and discouraging people from getting the jabs.

Among the disturbing developments to health officials are loud public fights between political leaders and pharmaceutical executives. In Europe, it’s an unusually public spat between officials and the company AstraZeneca, in which officials are accusing the company of allocating jabs meant for EU citizens for more profitable exports. Kuwait is locked in a contract dispute with vaccine maker Moderna that has delayed the shipments. In another incident, the German newspaper Handelsblatt sparked a panic when it reported, apparently incorrectly, that the AstraZeneca vaccine was not as effective on elderly people.

Experts say such delays, disputes, and miscommunications are a regular feature of pharmaceutical procurement and rollout, but more often confined to bureaucratic back offices and obscure science journals, rarely under such the glaring spotlight of 24-hour television and internet news.

“It’s very unusual that this is all happening in the public domain,” said Dr O’Neil. “It’s all playing out in real time.”

Politicians eager to posture for perceived domestic political gains in the introduction of vaccines are also risking public health. Leaders across the world wading into public health matters often do more harm than good.

Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu was publicly chastised and reprimanded by Facebook for urging Israelis in a video to submit the names and phone numbers of those reluctant to get the vaccine to the government. “Maybe they will get a surprise phone call from me and I will convince them,” he said in a statement posted online that public health officials say could feed into suspicions about covid inoculations.

Brazil’s far-right leader, Jair Bolsonaro, attempting to award loyalists and boost public confidence, packed his country’s health ministry with inexperienced military men who botched the procurement of vaccines, leaving a major country that is one of the worst-hit by the pandemic without nearly enough jabs, according to an investigation by the Reuters news agency.

Iran, which made a showy start of beginning human tests of its own vaccine, has spurned a donation by Iranian Americans of 150,000 jabs of the Pfizer vaccine, insisting it doesn’t trust medicine from the west. “It's not unlikely [the UK and US] would want to contaminate other nations,” Mr Khamenei said in a statement that was blasted as wildly reckless.

Public health experts have also warned that Israel’s successes in inoculating its own population could be undermined by its failure so far to inoculate to Palestinians living under occupation, damaging efforts at achieving herd immunity within two communities living in the same geography.

The long expected push by rich countries to grab vaccines is also a dynamic that public health officials are seeking to alleviate. While vaccinating one’s own citizens might provide a sense of security and domestic political benefits, without broad inoculation across the planet the pandemic will continue to fester. Poor vaccine coverage allows the virus to live, spread and mutate into more potent strains. Often it’s the poorest countries and communities that can least afford vaccines that most need them.

“Our biggest problem is that there hasn't been a new hospital built in our country since 1974,” Zdravko Krivokapić, prime minister of the small western Balkan nation of Montenegro, said in an interview. “Due to that fact, our healthcare system is much more vulnerable to the crisis. Our main hope lies in a vaccination campaign.”

WHO officials have launched a global distribution platform called Covax to help get vaccines to the poorest nations and develop a global approach to vaccination, but it has received scant donations compared to the billions spent by rich nations on procuring jabs for their own people.

Even within wealthier countries disparities between vaccinations among the rich and poor are emerging that could damage trust in the public health institutions as well as slow the alleviation of the disease. In the city of Chicago, for example reports suggest that residents of the city’s richest neighbourhoods in the north and northeast sides are getting vaccinated while those hardest hit and in most dire need are the least inoculated.

There have also already been numerous scandals involving the rich and the powerful jumping the queue to get a jab. Senior military officials in Spain were fired over getting their shots before the sick and elderly. In Canada, a casino mogul and his actress wife prompted public outrage for flying across the country to an indigenous region, flouting quarantine rules, posing as frontline workers to obtain a jab ahead of more vulnerable people.

“It could threaten the overall campaign if lots of vaccines are being directed to rich guys,” said Dr O’Neill. “The best-case scenario is that these vaccines are made available freely, and the priority is given to those who need them most.”

On the other hand, more than a few people have noted that the spectacle of the rich and powerful brazenly breaking the rules to push ahead of others to get inoculated early could also convince sceptics that the vaccines are safe. In Poland, for example, after word emerged that celebrities like actor Krystyna Janda had finagled vaccines ahead of their turn, enthusiasm about coronavirus inoculations jumped from 43 per cent to 70 per cent.

Shaun Lintern contributed to this report

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments