Boccaccio’s bawdy Black Death tales will take your mind off coronavirus

When forced to think about the unthinkable, we need a diversion – and the need for entertainment or outrage is normal in the time of a pandemic. As Kevin Childs explains, the way we react to a crisis hasn't changed much in 700 years

In lockdown the world can become almost a single room. Our minds turn inward, and when so much of what we listen to, watch or read is about symptoms and statistics and far off vaccines, it’s hardly surprising we want to think about something else. Sex, for many, is becoming a preoccupation. Keeping two metres away when we meet makes any sort of intimate touching difficult, transgressive, obsessive, even. When the history of this pandemic is written, will it be filled with tales of sexual encounters, both real and imagined?

Like virtually everything, we’ve been here before. Epidemics, such as that caused by Covid-19, have plagued human society since time began. A particularly devastating pandemic in the 14th century changed the western world forever. Called the Black Death, it was perhaps the deadliest epidemic in human history. It decimated the populations of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. At least a third of the people living in Europe died. In some places, it was far worse. The city of Florence in Italy, for example, may have lost up to 75 per cent of its population.

Whoever it was that walked through the gates of Florence in the early Spring of 1348 probably didn’t know they were sick. Or maybe they just had a bit of a temperature. But they’d brought the Black Death to one of the most populous, tightly packed cities in Italy.

“No human ingenuity or foresight could defend the city against it: not the vast amounts of rubbish which were swept from the city streets; nor the turning away of the sick from its gates, nor any of the recommendations for preserving public health that were posted daily in the main square...”

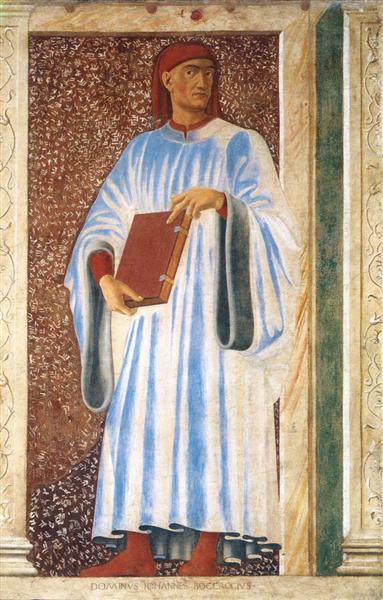

Giovanni Boccaccio, who wrote this, wasn’t wasting his time in lockdown. He may have witnessed the worst of the pandemic, but like so many of us, his mind was already elsewhere, compiling, editing and thinking up stories and romances – funny, bawdy, sad tales of love and sex for the most part – to entertain himself and a terrified public who were in need of distraction.

The stories he wrote down came from all over – India, China, Tunis and northern France – and although historical figures such as Henry II of England and Saladin appear, the majority are tales of a city, involving bricklayers and merchants, bankers and innkeepers, and they deal with love and desire, sometimes tragedy, more often raging libidos. It’s what makes them so modern.

But behind this parade of human comedy is the constant threat of death, as Boccaccio reminds us in his introduction: “So swift was the sickness that a man who woke up in the morning feeling fine, could be dead by evening. Some dropped dead in the streets where they stood, others alone and abandoned in their houses where only the stench of putrefaction alerted the neighbours.”

When he came to publish these stories, about two years after the plague hit Florence, he called the book the Decameron, meaning “10 days”, which is the time it takes for the tales to be told. For these are stories within a story.

One morning, so the narrative goes, in the summer of 1348, a group of friends, seven women and three men, meet at the church of Santa Maria Novella and decide to flee the plague-stricken city for a country house. They’re wealthy people from Florence’s merchant class, all single, perhaps because they’ve already lost husbands and wives, parents and siblings. They can afford a comfortable temporary exile. In a beautiful country setting they wonder what they’ll do with their time. As the leader of the group says: “We’ll hear the birds in the trees and see fresh green hills, and fields of corn rippling like waves on the sea in the cool breezes. Even heaven will show its face more clearly to us there than it does here.”

With servants to do the daily chores, cut off from the outside world, they entertain themselves with singing and dancing and playing games – the sexual tension is self-evident – but the main focus of their activities becomes the telling of stories. Ten friends each telling one story a day over 10 days, making one hundred tales altogether.

Others looked for the answer in partying until they dropped: drinking, eating to excess, dancing and having wild, abandoned sex were seen by this group as a means of keeping the pestilence at bay

And what tales!

Ever wanted to know what nuns really get up to in convents? Read the Decameron. Clueless young men are duped out of their money, rogues end up saints, and people are whisked through the night air on magic divans. There’s bed hopping in a country inn, holy men with unholy desires, and ghosts in the night are never what they seem. Some stories are so trivial they barely register in the imagination, some are utter filth, others resonate serious messages, about the nature of human relationships, about the need for kindness and the pain of lost love.

Our image of the Renaissance as a time of sex, scallywags and cynicism owes much to the influence of the Decameron. Its publication was a watershed moment. Those stories changed how we think. From anti-clericalism to an absence of deference towards authority, the bonds of marriage and the demands of parenthood, the Decameron’s impact was explosive. These are the seeds of the protestant revolution and modern enlightened thought. The Black Death would sweep away the old feudal system in Europe, but that system, with its rigid social barriers and top-down political structures, was already largely absent from republican Florence by 1348. The Decameron was a symptom of that shift, which explains its popularity among people of all backgrounds and classes.

As we watch the numbers who have died due to infection from Covid-19 rise every day, we can be selfish enough to console ourselves with the fact that most of us will probably survive. Florence’s brush with bubonic plague was far more lethal. For all the celebration of sex and desire, friendship and folly in Boccaccio’s tales, he didn’t want his readers to forget what they’d been through. The introduction to the Decameron provides one of the most detailed and frightening accounts of a plague, its symptoms, its devastating impact and the hopelessness people felt.

“It began with swellings in the groin and armpit, some of which were the size of apples and some like eggs. These swellings would then spread to other parts of the body, but then the disease changed tack and the body would be covered in dark, purplish spots on the arms and thighs, some large and widely spaced, some small and numerous. All these symptoms told the patient death would follow soon.”

There’s a lot we can recognise from our own 21st-century disease-induced lockdown in the behaviour of Boccaccio’s contemporaries. Then, like now, they fell into distinct groups. There are those who take self-isolation to an extreme, hoping to avoid any contact with the infection: “Some hid themselves away, living in isolation from any living person, eating little and drinking only the cleanest, freshest water or the most delicate of wines. Such people wouldn’t speak to anyone and shut their ears to any news, keeping their minds off things with music or entertaining books.”

Others looked for the answer in partying until they dropped: drinking, eating to excess, dancing and having wild, abandoned sex were seen by this group as a means of keeping the pestilence at bay, or an excuse for riotous behaviour: “These people behaved as though it were their last day on earth, thinking nothing of livelihood or possessions. Houses became common property ... But just like anyone else, they would run a mile if they came across the sick.”

And some sought a happy medium between the two, such as the friends who form the nucleus of Boccaccio’s narrative. But what characterised everyone’s behaviour was, in Boccaccio’s opinion, a total callousness towards those who were ill: “It didn’t matter who they ran from: brother abandoned brother, uncles nephews, and a sister her sibling; and what I find most hard to believe, fathers and mothers refused to visit, let alone nurse their children as if they were someone else’s.”

And then, there was the fake news. Charlatans and snake oil sellers abounded because traditional medicine seemed hopeless against infection. “Everyone had an opinion,” complains Boccaccio. Not surprisingly many turned to religion, at first massing in churches to pray, process behind crucifixes and kiss the relics, until the fear of contagion suggested that mingling in this way wasn’t a good idea.

His prime audience, he writes, are ‘those who are in love’ (or obsessing over sex), since the rest can preoccupy themselves with their hobbies and gardening and games

In fact, nowhere in Boccaccio’s account does God play much of a role. Unlike the vast majority of his contemporaries who saw the Black Death as divine punishment for the sinfulness of the world, Boccaccio is sceptical of the religious route. Nor was he in the blame game. Across Europe communities turned on their minorities, principal among whom were the Jews, and accused them of deliberately spreading infection by poisoning wells. Thousands were slaughtered as a result, with a general shift in Europe’s Jewish population to the east – Poland, Lithuania, Hungary – where attitudes differed, and infection rates seemed to be lower. The parallels with modern conspiracy theories hardly need drawing.

For Boccaccio, there was just a sort of inevitability about the plague. It was part of life; something to be endured, maybe, but also providing opportunities for an enterprising 35-year-old writer and novelty-hungry audiences.

So many of the stories from the Decameron betray the minds of their narrators and listeners. Sex is certainly everywhere, but the wish to be taken out of ourselves, to be diverted, entertained or outraged is only human in such circumstances. Above all, the tales are about human passion, for sex, for romance, for money, fame, living or a good supper. How these maddening feelings can be dealt with is key to the Decameron’s structure.

Boccaccio’s father and stepmother both died during the pandemic, adding to his sense of isolation at the time and reliance on friendship, self-fashioned narratives and invention. In a key passage in the introduction, Boccaccio talks about his own passion for an unavailable woman, which had led him almost to suicide, certainly into depression. Only the diversion provided by his friends helped him. It’s something we need to remember as we endure this pandemic. Feeling compassion for all those people obliged to spend long hours, “cooped up in their little chambers, in enforced idleness, wishing at one time this and in the next moment the opposite, forced to think about the unthinkable”, he used his own experience as an excuse for writing: “[I]f their minds should be invaded by sad reflections of some private passion or other, those reflections will take root and cause them pain, without something to distract them.”

After all, he’s saying, bawdy stories are as good a form of therapy as anything else.

Boccaccio’s own story reads like one of his tales. Born in or near Florence in 1313 of parents who were not married, when he was in his early teens his father and stepmother took their family to Naples. There he would flirt with his father’s trade of banking, study law at the university in Naples, fall in love with a daughter of the king, and eventually decide that writing was his vocation.

In 1341 he followed his now bankrupt father back to Florence, producing poetry, plays and prose romances, many of which would go on to permeate European consciousness through versions by Chaucer and Shakespeare, Moliere and Keats, to name a few. But the Decameron wasn’t meant to be a part of the canon of Italian literature. It was meant to be a diversion from the troubles of the time. His prime audience, he writes, are “those who are in love” (or obsessing over sex), since the rest can preoccupy themselves with their hobbies and gardening and games.

In reading [these stories]… you will be both entertained and… will understand what to avoid and what to follow, which will surely help drive out those negative feelings in our days.

Seeing the parallels between Boccaccio’s 14th-century lovers and our own 21st-century pandemic, we thought about the best way of making use of those lessons he talks about. How can we be taken out of ourselves? How can all those thoughts of sex, of desire, the effects of sheer boredom be dealt with? How can our anger at the failure of politicians and those in charge of our lives be channelled? What, in short, can we learn from Boccaccio?

So, we decided to record 10 of the stories from the Decameron, read by actors who are themselves self-isolating around Britain, and launch them as a podcast. We can connect across distances in a way that would perplex Boccaccio’s contemporaries. From our bedrooms and our kitchens and our garden sheds, from under duvets and blankets, using phones and laptops, we bring you the podcast Passion and the Plague: 10 tales from the Decameron. This is our campfire, or, in the case of Boccaccio’s friends, our green meadow embroidered with flowers and shaded by willows.

We start with the first story on the first day of isolation and end with the last story on the 10th day. Otherwise, the tales are selected from various parts of the book, but include fables such as the “pot of basil”, re-told by Keats in his poem Isabella, and Pinuccio’s and Adriano’s sexual adventures in an inn, used by Chaucer in his Reeve’s Tale. Boccaccio was both of his time and out of his time. So, his selection of tales is as valid today as it was nearly 700 years ago. Live life with passion, he tells us, and counter sadness with joy, for death is as much a mystery now as it was then.

Each podcast is a little journey of its own, into the minds of the characters, of the writer and, above all, of those reading. Let the stories take you away to another time, another place. Share the passion, the laughter, the sadness. But remember we are here and now, still part of the human comedy.

The Passion and the Plague is launched on Wednesday 20 May. You can sign up to listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Acast or whichever platform you prefer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments