With more in common than meets the eye, Britain could learn much from South Korea

This pandemic has highlighted the way in which the UK falls far short of the international best. Mary Dejevsky says South Korea’s thriving culture and government competence offer an example of how post-Brexit Britain could do better

Of all the countries so far ravaged by the coronavirus, one has stood out – in a good way. The early award for all-round most effective response has gone to one of the first countries to report the epidemic after China: South Korea. Compared with Spain, Italy and the UK, where those who have died from Covid-19 are now counted in thousands, the number in South Korea is currently nudging 220. Confirmed cases stand at fewer than 11,000.

In all the graphs showing the death toll as a proportion of the population as the disease spreads, South Korea is represented by an enviably flattish line all by itself towards the base of the chart. At a comparable stage of the pandemic, most European countries, the UK and the US are all bunched together rising in a similarly steep curve.

It cannot be excluded, of course, that South Korea will face a second wave of infection. Singapore, which was also affected early and also reported a relatively low rate of both confirmed cases and deaths, appears to be girding for just such an eventuality. But Singapore, by virtue of its small area and population (5.6 million), as well as its strict regulations on personal freedoms even in normal times, has to be seen in many respects as an exception.

South Korea is another matter. Its population (51.4 million), its status as a high-income country and its democratic system – though it is a relative newcomer to both categories – all make for many more plausible parallels with European countries. And there are particular parallels with the UK. The populations are not dissimilar (the UK population is 66 million), both are highly urbanised, with dominant capitals of around nine million inhabitants, and both are on the edge of continents, wedged physically and economically between major powers – China and Japan for South Korea and the EU and the US for the UK.

For all the similarities, however, the outcomes – so far at least – of the coronavirus emergency in the two countries could not be more different. South Korea’s success in fending off the infection will surely be the subject of many post-pandemic studies, and official figures will be pored over for many years to come. But several very specific factors already seem clear. South Korea was well prepared, having drawn lessons from the Sars epidemic of 2002-03 and the smaller Mers epidemic of 2015.

It started as it meant to go on, both in disseminating public information and in organising practical measures. It ordered thousands of test kits and used them – in line with the World Health Organisation’s recommendation to “test, test, test”. It followed up by methodically tracing the contacts of those who had tested positive, using mobile phone technology and ATM transactions to track likely contacts and warn others about infection “hotspots”. Those testing positive and their contacts were quarantined, mostly in their homes.

South Korea’s test, trace and quarantine approach turned out to be so effective that the country’s hospital capacity and medical supplies – personal protective equipment, ventilators and the rest that have become such an issue in the UK – have not been stretched in the same way. The individual approach to quarantine also allowed South Korea to introduce only very localised lockdowns, while the rest of life went on. Most factories, schools and businesses have remained open.

It might be worth noting that South Korea’s approach was the one initially favoured by the UK government – or so it seemed – when the coronavirus started to arrive in the UK. Test, trace and quarantine (self-isolate) is what happened to the first known British Covid-19 patient and his contacts when he arrived back from a conference in Singapore via a skiing holiday in Italy. It was also the way the first first cruise passengers were treated after repatriation.

As cases multiplied, however, this approach was quietly abandoned. The reasons for the change have not been spelled out. But it appears to have been in part because the UK lacked testing capacity and was late in trying to obtain more, and in part because tracing in the South Korean manner may have been judged unacceptably intrusive.

So we just don’t know whether South Korea’s approach would have been effective in the UK. It might not be suited to countries the size of the United States (330 million) or Russia (145 million), where the population is also spread out over much larger areas. It rather looks as though differences in capacity and policy are why the UK and other European countries did not follow South Korea’s example.

Despite heroic efforts of improvisation on the part of the government and the national health service, neither the UK’s medical, nor its technological, capacity comes near that of either Germany or South Korea

Germany, the one country that did follow South Korea to a considerable degree – though with more of a lockdown and less digital tracking – has so far reaped similar success. In fact, it has so far recorded an even lower ratio of fatalities to confirmed cases (0.6 per cent) than South Korea (1.4 per cent) – something that can be explained perhaps by the generally younger and fitter profile of those diagnosed and differences in how the cause of death is recorded.

Germany’s experience would reinforce the argument that it is less national specifics than capacity and policy that make the difference. As the past three months have shown, despite heroic efforts of improvisation on the part of the government and the national health service, neither the UK’s medical, nor its technological, capacity comes near that of either Germany or South Korea. This is something that is already giving the UK pause for thought, as the chief medical officer, Professor Chris Whitty, conceded at a recent Downing Street briefing when he said that Germany had “got ahead in terms of its ability to do testing for the virus, and there’s a lot to learn from that”.

While the UK may indeed have lessons to learn from Germany – in the way the German health system is funded and works – there are differences that would make it hard for the UK to take Germany as a model. Its federal structure would not easily reproduce in the UK, and the British resistance to European-style insurance-based health systems will doubtless persist. More profoundly, the two countries are currently on two quite different trajectories. Germany is institutionally anchored in the European Union. The UK has left the EU and seems intent on once again making its own way in the world.

Which is why, strange though it might seem, given their location on opposite sides of the world and their very different histories and cultural heritages, South Korea could be a pertinent model for the UK, especially after Brexit – and not just in how to handle a pandemic.

For all the distance that separates the UK and South Korea, the geopolitical parallels are striking. South Korea is pressed to the east by Japan – the one-time colonial power – and to the west and the south by the looming presence of China. Much historical baggage remains from relations with both – most sensitive to this day is the still unresolved dispute over compensation for the “comfort women” – the Koreans forced to become sex slaves to Japanese soldiers during the Second World War.

Despite ups and downs, however – and relations with Japan are currently on a down – South Korea has for the most part been able to negotiate a delicate diplomatic and economic path between these two great powers, fostering stable and largely productive relations with both. There is a large South Korean presence in China, made up of both commercial interests and students. Although the atmosphere generally is more fraught, something similar applies with Japan, and in both countries Korea benefits from not being regarded as the chief rival, i.e. not being either China or Japan.

Seoul’s relations with North Korea – since 1953, when the post-Second World War partition was reinforced by the outcome of the Korean War – have been patchier and less predictable. But the hair-trigger tension at the Demilitarised Zone at Panmunjom has been defused in recent years, culminating in the meeting of their two presidents two years ago, when they crossed the symbolic few feet into each other’s land.

South Korea’s diplomatic and economic success suggests that there may be advantages to being a smaller power sandwiched between big powers

South Korea was also one of the first countries to make economic overtures to Russia as it opened up under Mikhail Gorbachev in the last years of the Soviet Union and then after the 1991 Soviet collapse. One of its earliest and most eye-catching moves was when Samsung-branded baggage trolleys arrived at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo international airport. Samsung, LG and Hyundai are now all firmly ensconced in Russia.

If Brexit Britain is to put global trade front and central, South Korea offers an example of how to separate economics from politics and how not to be dominated by the United States, despite enjoying US patronage in the early post-war years and continuing defence protection.

In all, South Korea’s increasingly adroit pursuit of its own interests as Japan ages, China rises and Russia seeks more investment for its neglected far east offers a masterclass in how a medium-sized country, positioned between giants, can manage such three-corner relationships to joint advantage.

With the UK still to work out how it will handle its post-Brexit relations with the European Union and the US, South Korea’s experience, not just regionally, but globally, is worth more than a cursory look. Is balance the key, or playing big rivals off against each other, or maybe diversifying through cultivating ties elsewhere, with the Commonwealth, say?

Whatever the UK decides – and a major review of its foreign and security policy is currently on hold because of the coronavirus – South Korea’s diplomatic and economic success suggests that there may be advantages to being a smaller power sandwiched between big powers, so long as smaller size is accompanied by flexibility and lightness of touch.

Another way in which South Korea resembles the UK – equally improbable, given the geographical and cultural distance – is in the accessibility and attractiveness of its contemporary culture: high-brow and popular alike. South Korea in some ways might be equated with the Britain of the Sixties, as it emerged from the 1950s constraints, and its designs and its rock music swept the world.

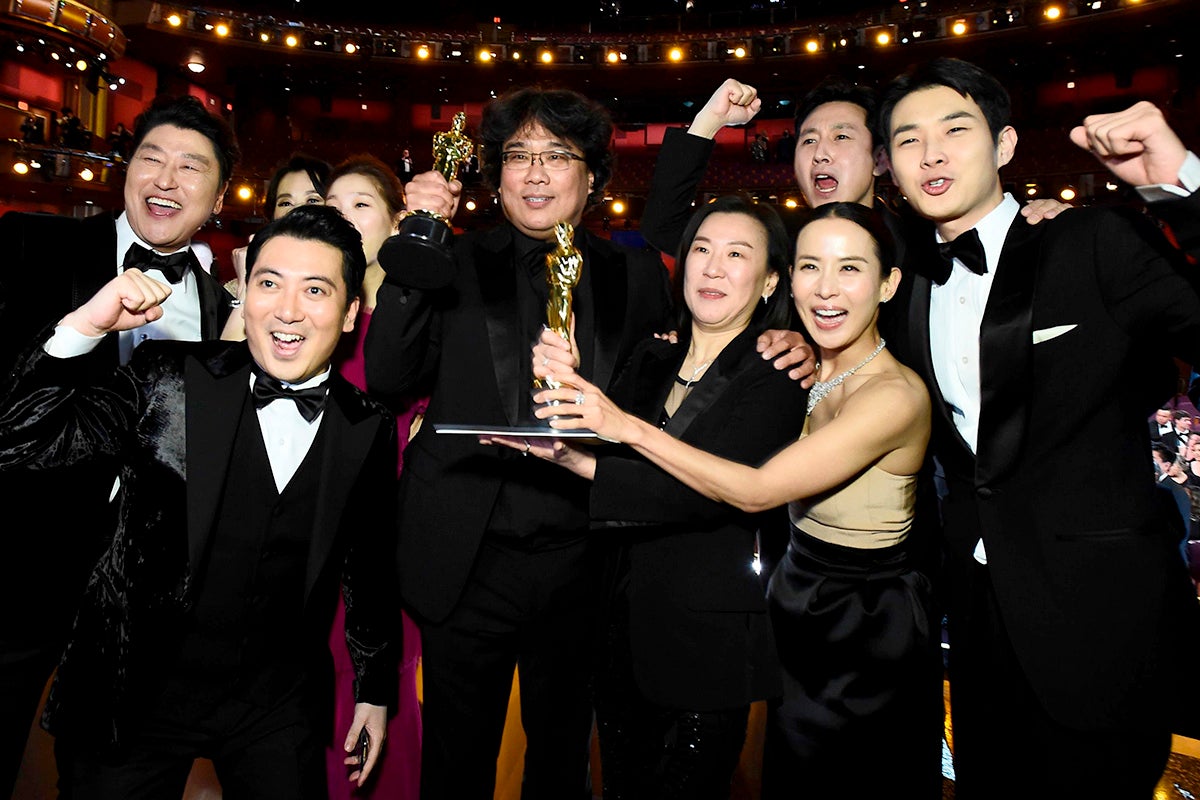

There was surprise, if not shock, in the Hollywood establishment when Parasite, by the South Korean director Boon Jong Ho, became the first foreign film to win Best Picture at the Oscars. The US president was not alone when he remarked in typical Trump fashion: “The winner is a movie from South Korea, what the hell was that all about?”

What it was “all about” was the steady rise to global eminence of South Korean culture generally. Not just cinema, but a wealth of art forms – from ceramics to painting, from pop music to literature – that has put South Korea squarely on the international map.

Not unlike the UK, from its post-Second World War Ealing comedies, to the Swinging Sixties, to Cool Britannia, South Korea seems to have unlocked the secret of a popular culture

Parasite is, in fact, a stellar example of how South Korea has been gaining an international presence out of all proportion to its size and quite at variance with the long-standing seclusion that led it to be dubbed ‘the Hermit Kingdom’. It is, said some, in the wake of the Oscars triumph, on the way to becoming a cultural superpower.

For those who have not seen it – Parasite is rooted in the extreme financial and social inequality that is a by-product of the country’s recent history and economic success. The villainous “goodies” are cellar dwellers who eke out a precarious existence from casual work and piggy-back off other people’s utilities and wi-fi. They outsmart the wealthy “baddies” – the family of a banker living in a luxurious modernist house in a plush suburb, with some black comic, and not so comic, twists. The locations – bar the house, which was just a set – have now become tourist attractions in Seoul.

What Parasite manages to do is to remain distinctively Korean and Asian, while exerting much wider appeal. There are echoes of kung-fu, graphic brutality that is at once both real and unreal, and a certain pitilessness in a storyline where almost everyone – no, make that everyone – behaves very badly. But the themes transcend their Korean setting and language, and result in a rip-roaring yarn, told with cinematic virtuosity, that speaks across cultural lines – including to western audiences still scarred by the 2007-08 financial crash.

Not unlike the UK, from its post-Second World War Ealing comedies, to the Swinging Sixties, to Cool Britannia, South Korea seems to have unlocked the secret of a popular culture that draws diverse audiences from far beyond its borders. More remarkably, it has managed this without the benefit of an international language.

The first ripples of what is now termed the “Korean Wave” were – and are still felt – in South Korea’s big neighbours, China and Japan. But the “Korean Wave” now laps at much more distant shores. Not only has it reached Europe, the UK and the US, but when I was in Cuba earlier this year, Parasite was showing in Havana.

South Korea has cracked the international literature market, too. In 2016, a South Korean author, Han Kang, won the International Booker Prize for her novel The Vegetarian. Its starting point is the 1980 crushing by the military authorities of pro-democracy protests in Gwangju, but like Parasite, it treats of much more.

Beyond literature and the film industry, it is in pop music – K-Pop – where South Korea has made its mark. Last year, BTS became the highest-paid boy-band in the world, attracting vast crowds of swooning teenagers wherever it performed and topping the UK charts last year with its album Map of the Soul.

Of course, there have been the downsides that come with extreme early success. At the tragic end of the spectrum, the pressures drove Kim Jong-hyun, a singer with the band Shinee, to suicide three years ago, at the age of just 27. At the most superficial level, K-pop star Kim Jaejoong had to apologise and cancel his bookings after claiming, in an off-colour April Fool, to be in hospital with coronavirus. All is not quite as innocent as it seems.

202.3m

Parasite’s box-office takings (dollars)

Nor as spontaneous either. As the Asia scholar Rana Mitter noted in his recent BBC radio documentary The Silent Cultural Superpower, K-Pop was the product of an industrial effort to rival Samsung and remains more or less stealthily supported by the state. This has not, however, detracted from K-Pop’s international success or the way in which it has effectively spearheaded South Korea’s new-found soft power around the world. One effect has been to spur a wider interest in South Korea among a new generation whose parents and grandparents knowledge of Korea probably extended no further than a fading awareness of the Korean war. Before the coronavirus pandemic halted most international travel, tourism to South Korea was up more than 50 per cent over five years, with more than 15 million foreign visitors in 2018.

In all, the UK and South Korea have a lot more in common than might meet the eye. In size and wealth, certainly, in their geopolitical dilemmas, in their determination to go it alone, and in the way in which they have developed and then capitalised upon a much wider cultural appeal. But there are also differences – beyond the obvious ones of history and culture – from which the UK, as it sets out on its new post-Brexit course, could perhaps find something to learn.

The first is its combination of energy, ingenuity and sense of purpose. Like the UK, South Korea, as Korea, is an old country with a venerable and singular heritage. But as an independent democracy and growing cultural powerhouse it is young. After a war that solved nothing and more than 30 chequered years of dictatorship and military rule, it became a full democracy in 1987. The military rulers, however, had used their power to create modern infrastructure and paved the way for South Korea to make the rare advance from aid recipient (in the 1950s) to aid donor (in the 1990s), avoiding the so-called middle-income trap along the way.

Whether the social solidarity currently to be seen in the UK in response to the pandemic persists after it is over – to the point where the bitter divisions over Brexit start to heal – remains in question

It is one of the most successful of the Asian economies. World Bank figures place it 12th in the world in overall GDP makes, and 31st in per capita GDP. The comparative figures for the UK are sixth and 24th – but the UK is on its way down, whereas South Korea is going up.

One reason cited for its achievements is that in the early post-war years it used US and then Japanese assistance well. As a proportion of GDP, government investment in R&D is equivalent to that of Germany and almost three times higher than in the UK. South Korea now boasts a health system – based on a universal system of state insurance with hospitals that are all privately run – that is regarded as one of the best not just in the region, but the world. Post-Brexit, the UK could do with showing some of that focus and drive.

Which leads on to the other area where the UK could usefully borrow from South Korea: the sheer competence of its government machine, regardless of who is in charge.

When I first went to South Korea a few years ago, I was struck – as many are – by its international airport, considered one of the best in the world. Even after a long-haul flight, without being able to speak or decipher a word of Korean, and instructed to take public transport to my destination in central Seoul, I found it simple to navigate. Contrast this with, say, London Heathrow, where despite being a native I have on occasion been hopelessly lost, and where baggage goes missing and computers go down. Seoul’s state-owned Incheon airport is a model of how to present an open and user-friendly face to the world.

My second epiphany was watching South Koreans present their documents. South Korea was among the first countries in the world to introduce a credit-card-sized passport/ID card with all the requisite information installed electronically. A decade ago that was an international novelty, and for many countries, the UK included, it still is. From street cleaning to utilities to its health service, South Korea is by and large a country that works.

It had the advantage, of course, of a late start. To be a pioneer, as Britain so often was – in rail transport, sewerage, a national health service and the rest – can be a liability when obsolescence sets in. This does not really explain, though, why the UK has such a poor record in initiating and completing big public projects, modernising its infrastructure, running efficient and joined-up public services, even policing its borders effectively.

In sheer competence it leaves a lot to be desired. And, as of now, it is hard to believe that any retrospective assessment of how it began to tackle the coronavirus will be much more complimentary. For all the admirable improvisation and dedication on the part of NHS staff and others, preparation appears to have been grossly inadequate, leaving the government to scramble, not always successfully, to catch up.

Competence matters, and it matters not only because it makes for more contented and cooperative citizens, but because it enhances public trust in the state – a commodity which has been sorely lacking in the UK, at least since the debacle of the Iraq war. In South Korea, there is a relatively high level of trust between rulers and the ruled, as there is in Taiwan – and, in Europe, in Germany – all countries whose approach to the coronavirus pandemic looks set to emerge well from the pandemic.

South Koreans, in particular, are judged to feel an unusually high personal stake in their country’s future – which periodically expresses itself in street protests, such as those that forced the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye in 2017. This sense of identifying with the state has been advanced by some as a reason why South Koreans, in turn, accepted some of the more intrusive precautionary measures in the current crisis, such as electronic tracking, that might be resisted elsewhere.

Whether the social solidarity currently to be seen in the UK in response to the pandemic persists after it is over – to the point where the bitter divisions over Brexit start to heal – remains in question. What this emergency has certainly done, however, is to highlight the ways in which the UK falls short of the international best – whether in the funding and capacity of its health service, its short-term approach to planning or the functioning of the state overall.

South Korea, by virtue of how much it has in common with the UK – its size and its high income status, its geopolitical dilemmas, and the flair and international appeal of its contemporary culture – could offer a template for those areas where the UK falls short: its sense of energy and purpose and the overall competence of the state. If the UK wants to make its mark in the world as a competitive, modern state post-Brexit, let alone set itself up as a model for others, it could do a lot worse than take several leaves out of South Korea’s book.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments