We are not ‘at war’ with coronavirus – we are treating it as we do all illnesses

Editorial: It is misguided to think of the government’s four-stage plan as a series of defensive lines that, once breached, mean automatic disaster

The language being deployed in the current coronavirus crisis is becoming increasingly belligerent. Former chancellor George Osborne has called for the government to be placed on a “war footing”, while the prime minister has termed the NHS action plan a “battle plan”. Our foe has a foothold in every continent bar Antarctica. Though not driven by any conscious malevolent motive, coronavirus is the “enemy”.

Yet it is wrong to think of the government’s four-pronged approach as a series of defensive lines that, once breached, mean automatic disaster. The chief medical officer Chris Whitty’s announcement that officials are moving towards the second phase of their response to the outbreak should not, in other words, be cause for too much concern.

Transitioning from the “contain” to the “delay” phase is in truth matter of tactics and degree; there was always a good deal of overlap between the two. Anyone wanting to minimise their risk of infection (to coronavirus as well as colds, flu and other illnesses) will need to continue to wash their hand thoroughly, throw tissues away and be aware of the onset of symptoms in themselves or others. That will never change, and is sound hygiene in any case.

Some areas of the country and categories of people will be suffering higher infection rates than others, though Britain is too small to regard any corner as immune to the virus. That is why the reporting of geographical and daily statistics can be dangerously misleading. The switch to weekly national bulletins is welcome. Panic, too, is a danger.

The authorities are right to be contemplating the careful adoption of specific measures to delay the progress of the disease. That may mean the postponement of major sporting and cultural events, conferences and other mass gatherings. It could also mean, at the margin, that those workers who can more easily work from home should do so, and that the public might be asked to make less use of public transport and so on.

The benefits of containment and delay together are mostly to do with buying time – for the NHS to move away from its usual winter pressures into the spring and summer. Warmer, drier days will help patients get through any infection more comfortably, reducing complications and pressure on bed space. There will also be more time for the third stage of the action plan, the one that may bring the most results: research.

It is impossible to say how long it might take to develop a vaccine for this mutating virus, but the longer the outbreaks can be contained and delayed, the more time there will be for a vaccine to be developed, tested and manufactured.

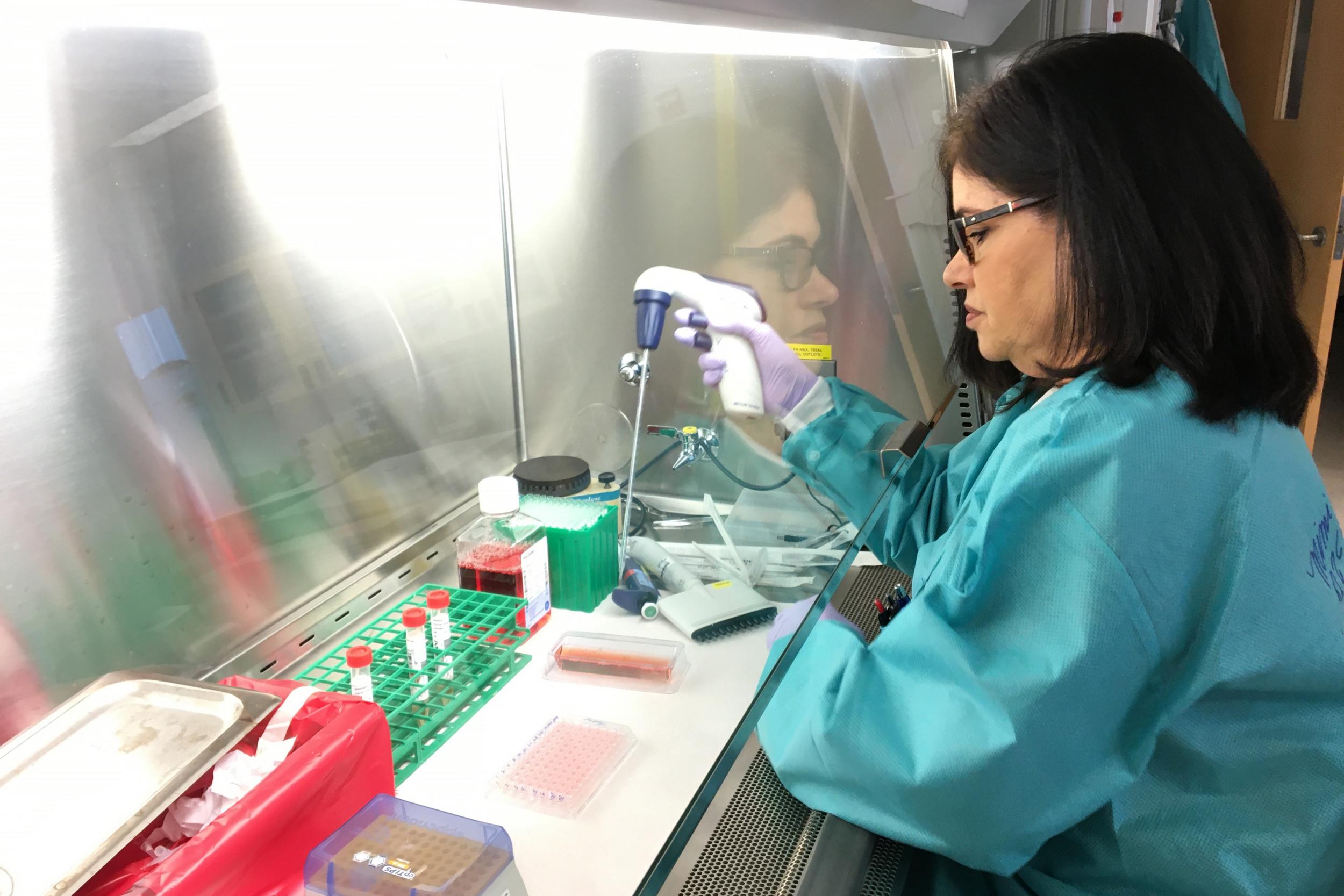

That leaves us with the fourth, unavoidable part of the plan: mitigation. This involves the best possible treatment of people with Covid-19, and supporting medical staff as they try to cope. Again, for those badly ill, extra resources will need to be found imminently, non-urgent surgery postponed and staff brought out of retirement. It might also be prudent to assist EU nationals to stay in the UK indefinitely.

If this is a “war” on a flu virus, then victory can never be declared because these viruses constantly mutate, in humans or other creatures. That does not mean that every increase in the number of cases is another step along the path to defeat. It means that modern medicine is needed to deal with it, as with every ailment. Yet the most potent weapon in the anti-coronavirus armoury looks to be the most basic: personal hygiene.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments