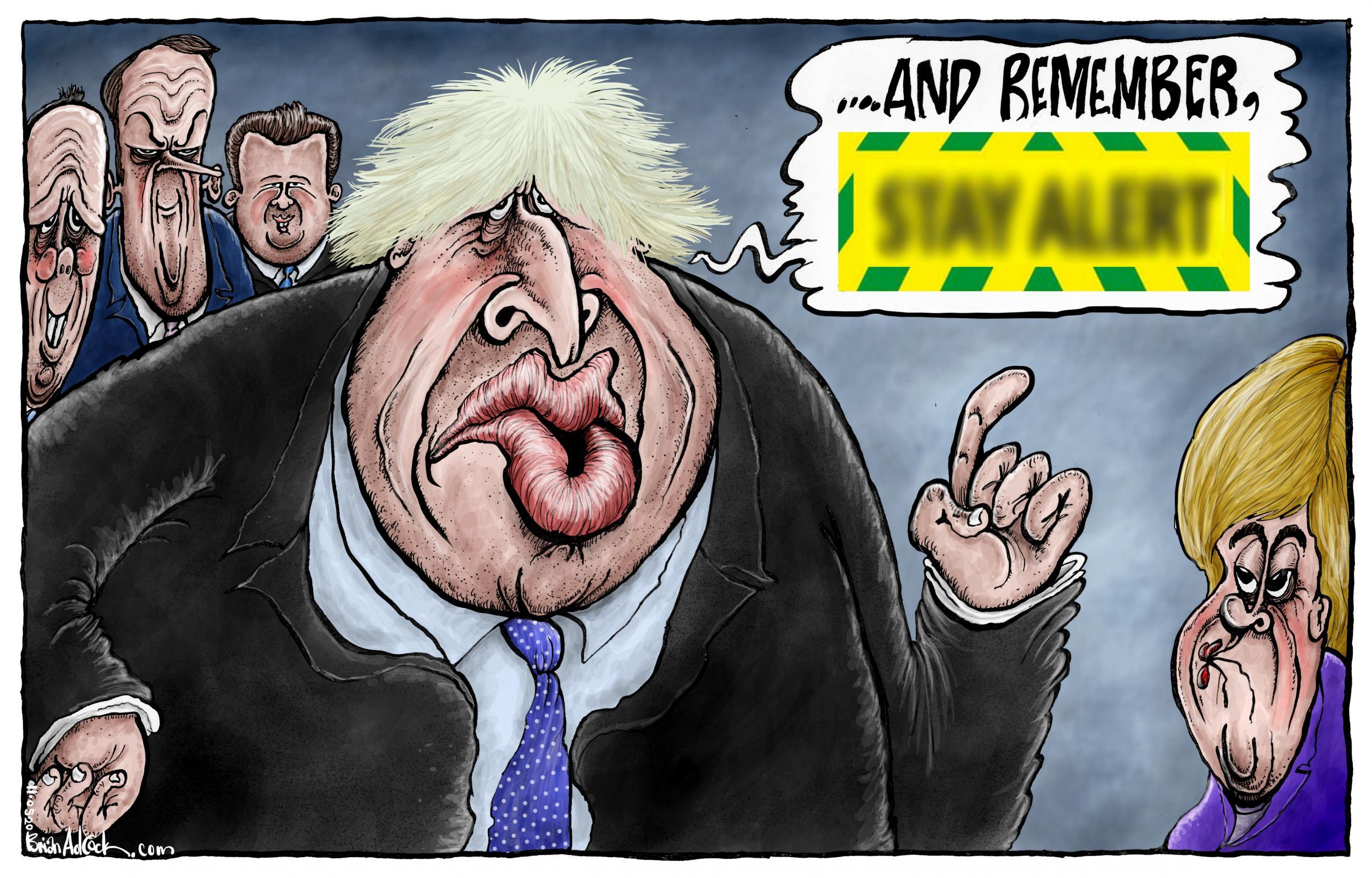

Now is not the time for mixed messages – nor for Boris Johnson striking out on his own

Editorial: If the government wants to use a new Covid-19 slogan, politicians – and more importantly the public – need to understand what the alteration means and why it has happened

From the moment the government’s new coronavirus slogan first emerged, there was criticism.

Then, on Sunday lunchtime, in a somewhat more serious intervention, it was aggressively disowned by Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon. Arlene Foster, her Northern Ireland counterpart, also said officials from the region would not be deviating from the original message. While Wales’s health minister, Vaughan Gething, tweeted there had not been a “four-nations agreement” about any change.

So just for England then, “stay home” has been replaced with “stay alert”. The second message is no longer “protect the NHS” but “control the virus”. Part three is still “save lives”.

The disagreement – with the stay-at-home regulations being controlled by each devolved government – is a highly undesirable state of affairs for life in this country.

Coronavirus has done precious little to depolarise the UK. There are millions, tens of millions even, who loathe Boris Johnson, and who will pass up no opportunity to take the most damning reading of anything the government does.

But even the most generous judges would conclude that the new messaging is poor. What does “stay alert” mean? Nicola Sturgeon was asked this very question, to which her reply was, “I don’t know.”

Tory MPs have been busily explaining how obvious it is what the new slogan means. It means, apparently, follow the rules. The communities and local government secretary, Robert Jenrick, has said that it means “stay at home as much as possible”. We have subsequently been given explanatory notes as to exactly what “stay alert” means.

But if you have to explain what a slogan means, then clearly the slogan hasn’t worked. There is a reason top advertising agencies are paid huge sums of money, often to produce little more than half a sentence.

Leaving someone with no doubt as to what’s required of them, while taking up no more than two or three seconds of their attention, is a difficult business – and the government has got it rather badly wrong.

As for “control the virus” – the entire point is that the virus is invisible. Many people have likely already had it pass through them, asymptomatically. Others have it within them currently, but will not know for some time.

In a sense, the last days have vindicated what might have been wrongly perceived as mistakes by the government several weeks ago. It does appear that the concerns of the so-called nudge unit might not have been without merit. That lockdown had to be timed right, so that people would not tire of it at the wrong moment.

And people do seem to be tiring of the lockdown, and are taking more risks with their own behaviour. But that is why it is not a time for increased ambiguity about what behaviour might be possible.

Nicola Sturgeon is regularly praised as a highly able and effective politician, which she is. But not all aspects of being a politician are entirely noble. When she said on Sunday that it was not sustainable for the leaders of the two governments to read of each other’s plans “in the pages of the newspapers”, she did not mention that, on previous occasions, she has taken it upon herself to announce UK-wide government policy hours before the prime minister has had the chance.

A politician’s primary duty is to keep their people safe, and if there is an opportunity to claim to be doing this while taking a swing at your opponents, an effective politician will certainly take it, as Ms Sturgeon has done.

Ultimately, the most significant news that has emerged in the last few days are the views of two scientists. The first was Sweden’s Anders Tegnell, who has defended the no-lockdown policy in his country, for which he bears responsibility, claiming that lockdowns will achieve very little. That, in the end, they will have to be eased, and all countries, regardless of policy, will come to have very similar fatality rates.

The second was from the virologist Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who advises the European Commission on coronavirus and almost died from it himself. “Let’s be clear,” he wrote. “Without a coronavirus vaccine, we will never be able to live normally again … and it is still not even certain that developing a Covid-19 vaccine is possible.”

Ultimately, no one has a roadmap out of this crisis, and the tweaking of government slogans is scarcely even worthy of a signpost along the way.

Until this point, however, people did at least appear to have some understanding of what they should and shouldn’t be doing, even if some chose to ignore it.

At the moment, all that is certain is uncertainty. It is hardly the time to introduce even more ambiguity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments