‘It is very rewarding’: How two refugees are working as NHS doctors during coronavirus outbreak

‘I am very proud to get this opportunity because the UK helped me a lot,’ Dr Ahmad Alomar says

Thousands of miles from home, Syrian refugees in the UK have found themselves on the frontline of the UK’s coronavirus outbreak.

“Sometimes I feel stressed because of the fear of catching the virus or the fear of what would happen,” says Dr Hamad Hawama. “But most of the time I feel very proud.”

“It is very rewarding to pay back to the community and to be someone who can help and support others,” the Syrian national tells The Independent.

Dr Hawama, a doctor in a Southampton A&E department, is one of hundreds of doctors with refugee status registered to work in the UK.

Once a cardiology trainee in Syria, Dr Hawama says he fled the country after Isis took over his city of Deir Ezzor, travelling to Turkey before arriving in the UK in 2014.

“I worked for more than three years in Syria, but I started from scratch here because I didn’t work for more than five years when I was a refugee,” the 37-year-old foundation doctor says.

“I was doing my English exams. It was a very tough and difficult time for me. I was even homeless for a period. I used to sleep in night shelters.”

After passing his exams, he qualified as a doctor and is now working at an emergency department.

“I feel rewarded and loved now. It’s not only me, any NHS worker feels very proud they are working for the NHS. People are clapping for them and supporting them,” he tells The Independent.

“It’s a nice feeling I can now support the community and the NHS.”

Refugees must pass an English language and a clinical exam, as well as do a work placement in a hospital, in order to work as a doctor in the UK, according to the General Medical Council (GMC).

There were 313 doctors who held refugee status on the GMC’s register with a licence to practice in the UK as of the end of March, a GMC spokesperson told The Independent.

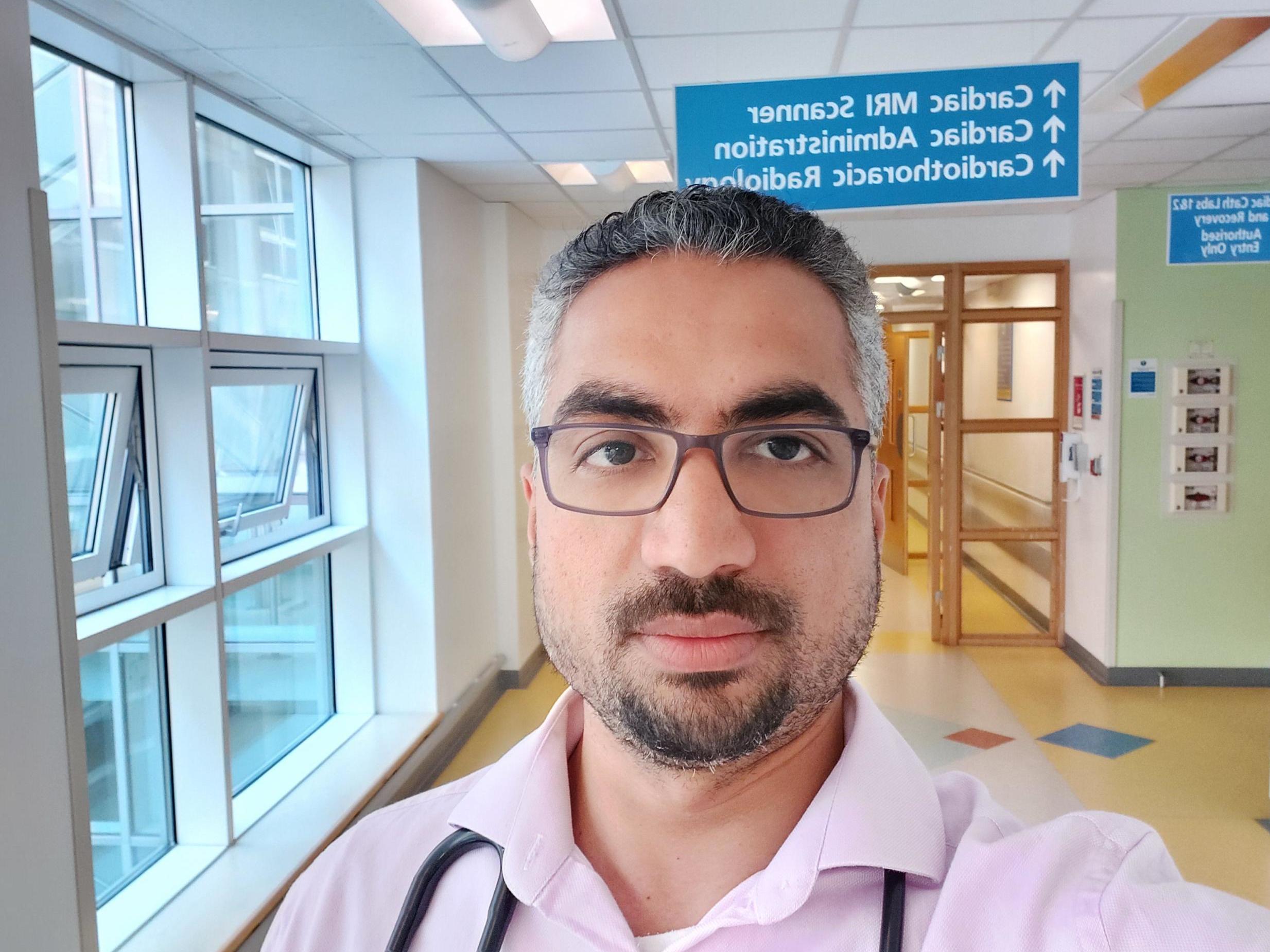

Similar to Dr Hawama, it was years before Dr Ahmad Alomar, also a Syrian national, completed all the steps to work as a doctor in the UK.

“I was working at my private clinic, then everything was destroyed and I had to flee from my country and build everything again from scratch,” the 40-year-old, originally from Hama, tells The Independent. “I didn’t practice medicine for six to seven years after I fled from my country until I started my job here.”

“The main problem was the English exam,” says Dr Alomar. “Once it was done, everything went through very quickly.”

He adds: “I’m very glad I’ve come back to my career.”

Now, Dr Alomar – who says he fled Syria after he was detained by authorities for several weeks during the civil war for treating patients in areas outside of regime control – is now working on Covid-19 wards in Oldham, Greater Manchester.

And he has offered to move to intensive care units. “I felt there might be a shortage in staff at any point so I had to tell them I’m here if they need me,” he says.

He tells The Independent it was a “great honour” to work on the NHS frontline during the coronavirus pandemic in th UK, where around 195,000 people had been infected with the virus as of Wednesday.

“I am very happy and very proud to get this opportunity. Because the UK helped me a lot at the beginning.”

Dr Alomar, who studied medicine at Aleppo university, says it was scary at the beginning when not much was known about the disease and he was worried about his family, who joined him in the UK a year after he arrived.

He says he makes sure to keep personal items away from his two children, washes his car often and changes all his clothes after returning home from the hospital.

He had to self-isolate for a time after showing symptoms of the virus, which can give carriers flu-like symptoms and can develop into pneumonia.

Meanwhile, Dr Hawama says one of the scariest things for him during the Covid-19 outbreak is not having family in the UK.

“Sometimes I feel stressed that if anything happened, I don’t have family or someone to look after me,” he says. ”At this time, if your family is not with you, you feel more stressed.”

But he says he has felt the community come together during the crisis, with people lending a helping hand to others.

“Throughout difficult times, it shows you how people come together and support each other and become closer to each other,” he says.

“I think this is a normal reaction, to look at the people who need support at the time of crisis and help that. I found that here in the UK and I found that in Syria.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments