It must have been a tough call for Dominic Cummings and Boris Johnson: should the prime minister’s most senior aide issue an apology, or something resembling one, for his breaking the rules on lockdown?

To his credit, in a way, Mr Cummings, deploying the cool logic for which he is renowned, saw no reason to express regret, contrition or make any apology because, in his view, he didn’t do anything wrong. He didn’t even try to appease an angry public with what might be called a “Tony Blair” or “Priti Patel” version – “I’m sorry if people feel that way”.

Hence the harsh headlines and growing mood of resentment. One opinion poll that registered a vote of 52 per cent for Mr Cummings to leave his job now shows that 59 per cent want him gone. Some are asking questions about whether he was as prescient about the coronavirus pandemic as he claims to be.

The furore is not dying down, and shortly Mr Johnson will face the Commons Liaison Committee, who will rightly want to know how much responsibility he takes for his nominal underling, what he knew and when, and exactly why this Svengali-like figure is judged so indispensable that he is placed above the law. The investigation of the facts by Durham Police may shed yet more light on those.

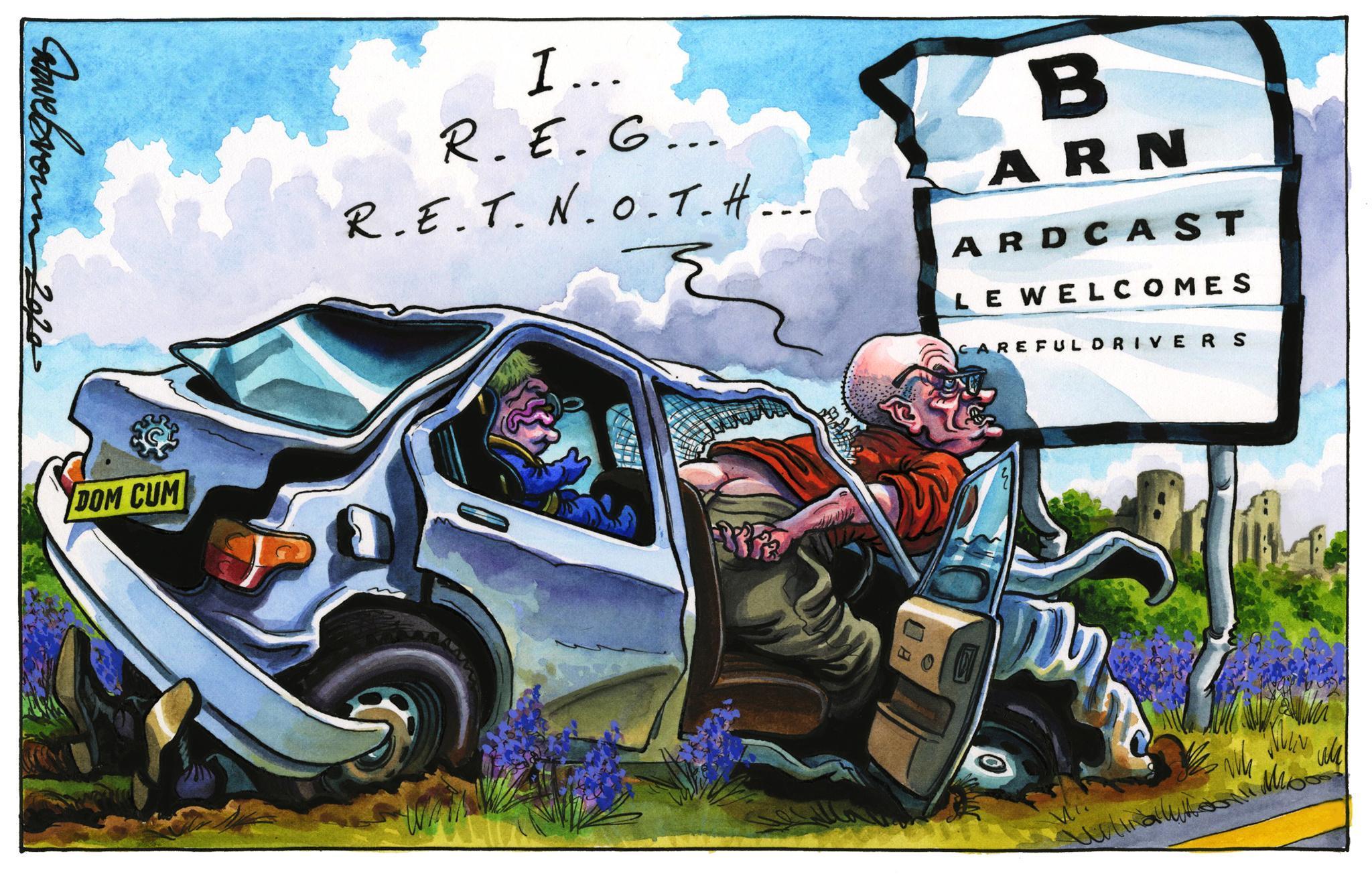

Conservative MPs are mostly unimpressed by Mr Cummings’s version of events – not least because the protests from constituents are still pouring in, and those in marginal seats may be especially concerned about any lasting resentment. Michael Gove, the man most responsible for inveigling Mr Cummings into power, made a poor show of justifying a 30-mile ride to Barnard Castle as an obvious way for someone to try to check their eyesight; he made a tall story sound sillier.

Cabinet colleagues, MPs, Tory grassroots and voters alike may wonder why they are being gaslighted in this way. They are not foolish enough to believe that Mr Cummings acted in a reasonable and legal way, and certainly not that he acted “with integrity”. Everything Mr Cummings achieved in his trip to Durham could have been accomplished if he had obeyed the rules and stayed at home in London. He risked spreading the virus in his various visits, and the “Cummings effect” is eroding the continuing official advice about social distancing and staying at home.

As the exit strategy from lockdown gathers pace, this damage to the credibility of official advice may prove catastrophic. If a second wave of infections does overwhelm the NHS in the coming weeks, then the government will not be able to offload the blame. The political consequences of a Lombardy-style collapse are unknowable.

Even now, on the best of the measurements, the UK has suffered one of the worst per capita mortality rates in the world. The level of infections and the R rate are still too high, relative to the test-and-trace infrastructure, yet the lockdown is still being eased, and the government’s credibility is now trashed, as the Sage behavioural scientists say, by Mr Cummings’s actions.

The government is running too many risks with other people’s lives: Mr Cummings is part of the problem.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments