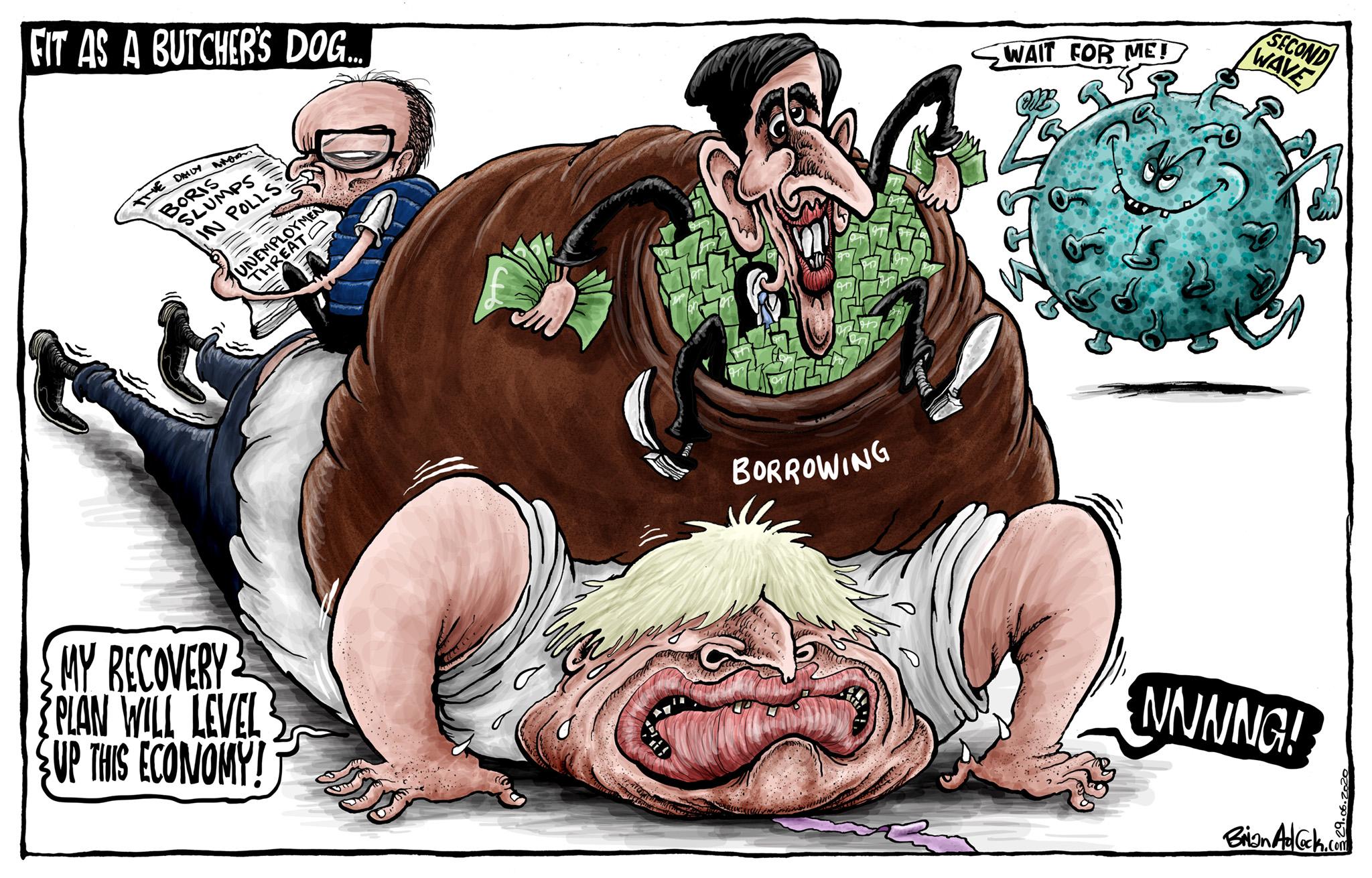

How to pay for this crisis? Boris Johnson’s answer to the question is to just plough on, as so often with the tricky stuff. This time, though, he may be right to do so.

In a speech later this week, we are told, he will pledge not to return to austerity and will launch “Project Speed”, a great ramping up, as they say, in infrastructure spending. Priti Patel has confirmed there will be no retreat on the “levelling up” agenda. The modernisation and construction of hospitals, schools, roads and prisons will be stepped up. Broadband will be upgraded. The government will keep the economy afloat as it recovers from its shocks.

It is an ambitious plan, though a relapse into a second national lockdown may overtake it.

Although entirely unplanned, this Conservative government’s economic response to the Covid-19 crisis in fact represents a huge extension of the progressive principle of social insurance. Instead of those families and businesses hit hardest by the lockdown being left to fend for themselves and take the consequences of their bad luck, the nation has “put our arms around” the people in trouble.

Even though some of the assistance has been conditional and in the form of “bounce back” loans, and some people have missed out, it is the same socialistic principle that underpins the National Health Service. Without it, the economic collapse would have been even more precipitous, and even more costly to the nation as a whole in lost output and mass unemployment. Morally, but also financially, the unprecedented range of measures provided by the Treasury and the Bank of England has been the right thing to do.

Still, it means a bigger state, and it will all need to be paid for some time, somehow. Part of the funding will come in the repayment of the recent loans to business, though some will need to be written off; the infrastructure investment should more or less finance itself via higher future productivity.

An increasing proportion of the borrowing has had to be funded by the Bank of England creating new money, rather than from investors lending to the government. This has caused little alarm at the moment, with inflation subdued, but is not an infinite resource. The cost of servicing the debt is also currently minimal, given globally low interest rates. Again that may not pertain forever. The state has to allow itself some contingency to avoid the moment when it runs out of credit but has to deal, say, with some future banking crisis.

Fortunately, that danger still seems distant. The British national debt now represents about 100 per cent of GDP, against less than half that proportion before the financial crisis, which was followed by a decade of mostly futile austerity and now the coronavirus pandemic. Yet the national debt was two and a half times larger at the end of the Second World War than it stands today, and it gradually declined to a low point of about a fifth of GDP in 1991.

The traditional way the British eroded their debt and liabilities was through a combination of domestic price inflation, devaluation of the external value of sterling and some economic growth. Thus was any formal default avoided. The future long-run challenge, then, is to avoid inflation and to boost growth and Britain’s woeful levels of productivity.

This will be made doubly difficult if the economy emerges from this crisis burdened by levels of unemployment last seen in the 1980s, as Ed Miliband now warns in his role as shadow business secretary. Brexit will also exacerbate the challenge of exporting to our largest market, the EU. Growth will be a struggle.

That is why everything has to be done to extend the support to save the economy now, to prevent another generation facing years of difficulties. There is no alternative, to recall a phrase from the past, to borrowing and spending our way out of this unique recession. In time, paying for the crisis will be the responsibility of the whole community, through progressive taxation over many decades.

For now, though, the government should worry less about paying for the crisis and more about alleviating it. It seems Mr Johnson may be grasping that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments