‘We are paying with our lives for austerity and incompetence at the top’

The government has been accused of 'massaging the metrics' to reach its target of testing 100,000 people a day. With such an ill-informed strategy, the chaos was hardly surprising, writes Arron Merat

The health secretary’s target, belatedly announced on 2 April, of conducting 100,000 tests by 30 April always seemed like a tall order. Public health budgets had been squeezed under a decade of austerity. British virology labs had exhausted the traditional procurement channels for the chemicals they needed because other nations with established testing policies had bought up all the stock. “The target was a communications exercise,” one official at Public Health England (PHE) told me. “I think he set the target when he did to avoid bad headlines in the short term.”

In the end, Matt Hancock’s target was met – but he had to change the rules just before the deadline to include tens of thousands home tests that had been sent out but not been processed.

And on the eve of the deadline, NHS Providers said the target itself was a "red herring," acting as a PR distraction from the real issues.

I have spoken to doctors, clinical virologists and officials involved in hitting this target, who have described the logistical and procurement problems that beset their efforts.

According to decades of virology research and World Health Organisation (WHO) advice, early mass testing is indispensable to save lives during a pandemic as contagious as Covid-19. Testing allows you to determine important data such as the size of the infected population, the size of the asymptomatic population and the virus’s reproduction rate. However, testing for most of April hovered stubbornly at around 20,000 tests a day, while Germany maintained a steady average of 50,000 tests a day. During that month, Britons have been four times more likely to die from the virus than Germans. What went wrong?

People in Britain, whose government is testing around 20,000 a people a day, are four times more likely to die from the virus than Germans, whose government is testing 50,000 a day

Sixteen years ago, a virology lab in Cardiff took a phone call from a GP in rural Wales. An elderly patient was suffering from flu-like symptoms and the practice wanted to use Tamiflu, a new drug that could only prescribed if the patient tested for influenza. The doctor did not have the official kit to send off the suspected viral sample, so he simply took a swab, bagged it up and sent it to the capital.

At the Welsh central testing lab, clinical scientist Catherine Moore received the package. At that time, policy stated that samples of suspected viral infections should be transported in Virus Transport Media (VTM), a specialised solution in which cell debris from the back of someone’s throat – and any virus lurking within – is suspended and sealed.

Catherine, who is now a consultant at Public Health Wales’ Specialist Virology centre, worked up an ad-hoc process to extract enough nucleic acid from the cotton wool at the end of a stick to do a molecular test. To her surprise, she found a positive result for influenza RNA. Tamiflu was duly prescribed, and Catherine began to wonder. What was the point using VTM to transport viruses at all? They were expensive, required refrigeration, perished after six weeks and, in her estimation, had a higher risk of accidental infection. To be sure, she ran controlled tests with infected dry swabs and infected VTM and found the cotton wool at the end of a stick gave more accurate results.

“From then we started looking at how we could implement that much wider,” Catherine told me. She puts what she sees as an unnecessary use of VTM down to a mix of dogma and institutional inertia and refutes concerns that her method increases the chance of degradation of the viral genome. “People just get stuck in their ways, don’t they?” Catherine contends VTM is just a hangover from the days when viral infected cells needed to be kept alive during transportation to labs. Even 16 years ago, she explained, advances in molecular science meant that viruses no longer needed to be kept viable (or infectious) to test for their genes. Catherine’s thrifty dismissal of VTM products is now Welsh health policy.

For a crucial two-month window after China’s lockdown, in response to the spread of Covid-19, the British government resisted pressure to test its population – even frontline NHS staff. Between late January and early March, the government cleaved to a theory of herd immunity. On 5 March Boris Johnson – who is recuperating after being infected with Covid-19 – sat on the This Morning sofa. “One of the theories,” he told Phillip Schofield and Holly Willoughby, “is perhaps you could take it on the chin, take it all in one go, and allow the disease, as it were, to move through the population.”

On 9 March, the day Rome instituted a national lockdown the British government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, said the elderly could go to church and stated that public events could go ahead. “You can’t and shouldn’t” stop interaction between people, he said. Exactly two weeks later, on 23 March, once it became clear this strategy would overwhelm the NHS, the prime minister changed tack, instituting a lockdown and setting ambitious targets to test NHS frontline staff and people with symptoms.

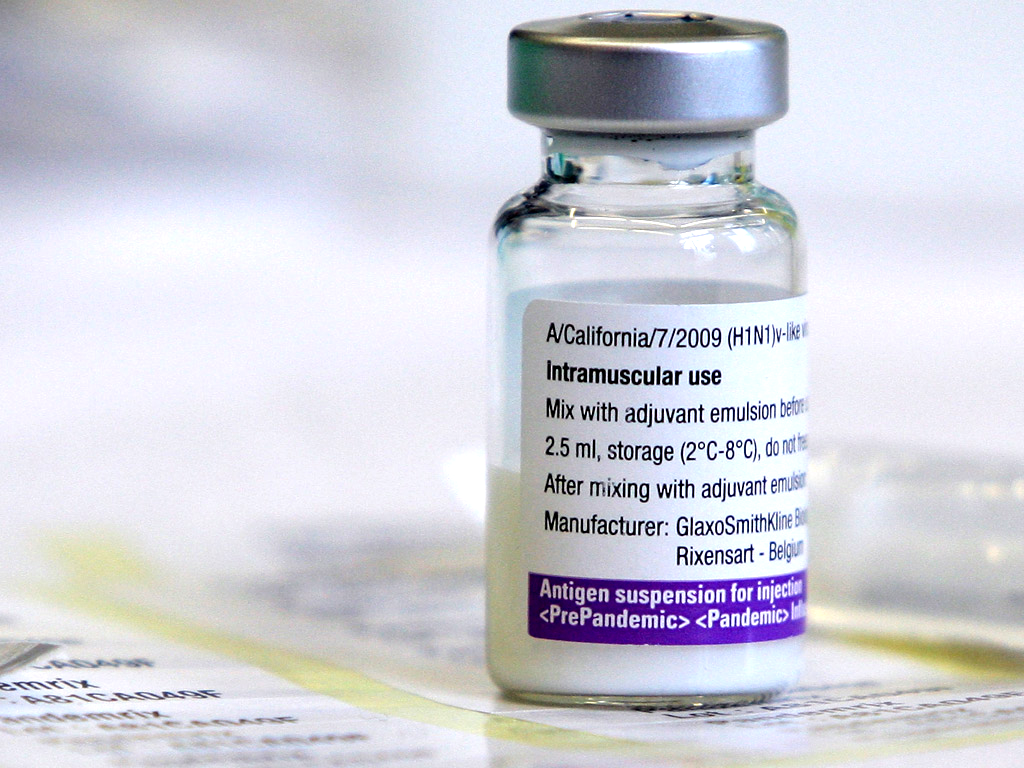

On 2 April, Matt Hancock, the health secretary, belatedly sketched out a testing strategy, which would bring in hospitals, occupational health clinics, research institutes and universities. The problem for the institutions tasked with running these tests was that almost all of the world’s commercial stock of reagents required to run them had already been bought up. Chemical giants such as Hologic, Qiagen and Roche, which provide the bulk of Britain’s reagents, could not make them anywhere near fast enough.

People tend to just follow the protocols. ‘Oh well, this is the machine, you buy in these chemical kits and the machine gives us the result.’ They often don’t understand the chemistry

Most of Britain’s virology labs are bound to these firms by managed service contracts. They supply Britain with diagnostic kit and chemicals, in effect creating a dependence now exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Francis Crick Institute, Britain’s leading biomedical research centre, was a major player in rolling out testing for several hospital trusts and occupational health departments in and around London, the worst affected area of the country. Dr Rupert Beale, the group leader of Crick’s Cell Biology of Infection Laboratory, found this dependence on “proprietary rubbish” early on in the outbreak an impediment to scaling-up testing.

“Some people quite high up dropped the ball early on,” he said. Beale describes the weeks early on in the crisis where the British public health system failed to adapt its business-as-usual approach to get what it needed. “You need a plan A but also a plan B and C. The Plan A we got was based on proprietary reagents. It was not thought through.”

Beale described “an inertia” at an operational level. “There was an awful lot of ‘Oh, you can’t possibly’, and perfection, ludicrous perfection,” Beale told me. “People tend to just follow the protocols. ‘Oh well, this is the machine, you buy in these chemical kits and the machine gives us the result.’ They often don’t understand the chemistry.”

Wales gave Beale an answer to the question of how to wean one of London’s biggest testing pipelines – run by partnership between the Crick, local NHS trusts and University College Hospital – off proprietary reagents. He read Dr Moore’s paper on her dry swab protocol and instituted the principle into Crick’s London testing pipeline, which has a capacity of between 2,000 tests per day – 3,000 at a push. No need for proprietary reagents or swabs to transport samples from across the Greater London area.

There was also the problem of what to do with Britain’s last multi-format proprietary swabs. “We needed to set up one pipeline. Multiple pipelines for each of the company’s swabs would have been a disaster,” Beale said. Here, PHW also provided a solution. The Crick was receiving hospital samples in different formats, mostly in VTMs and from different companies. Dr Moore suggested simply depositing the incoming swabs, dry or VTM, into a home-made guanidinium solution with soap.

“It worked first time,” said Beale. On Thursday, the Crick made public its own protocols, including the dry swab method and on Friday the Department of Health released a call for “novel solutions to help deliver 100,000 coronavirus tests a day by the end of April,” citing the dray swab test as one of four priorities.

Austerity and incompetence at the top means that we were just not prepared for this

“All of this basically requires carbon nitrogen and oxygen. So, if you’ve got that, and you’ve got a lab you can make anything you want,” Beale said. “It’s just that people are so used to using made up prepared kits. It’s like saying we’ve run out of macaroni cheese, because we don’t have macaroni cheese ready meals, when you have both macaroni and cheese. We’ve forgotten how to cook for ourselves”.

Over the past three weeks, said Beale, problems of Britain’s attempts to increase testing capacity have been ironed out. Institutions are doing more of their own chemistry and big companies such as AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline repurposed equipment and their capacity climbed. Unfortunately, the government faced a new problem. Now that capacity was moving in the right direction, logistical problems meant that half of it was going unused. Swab samples were simply not arriving at labs anywhere near fast enough to test them.

Sir Patrick Vallance, the government’s chief scientific adviser, admitted in mid-April that Britain had failed to increase testing “as fast as it needs to scale”.

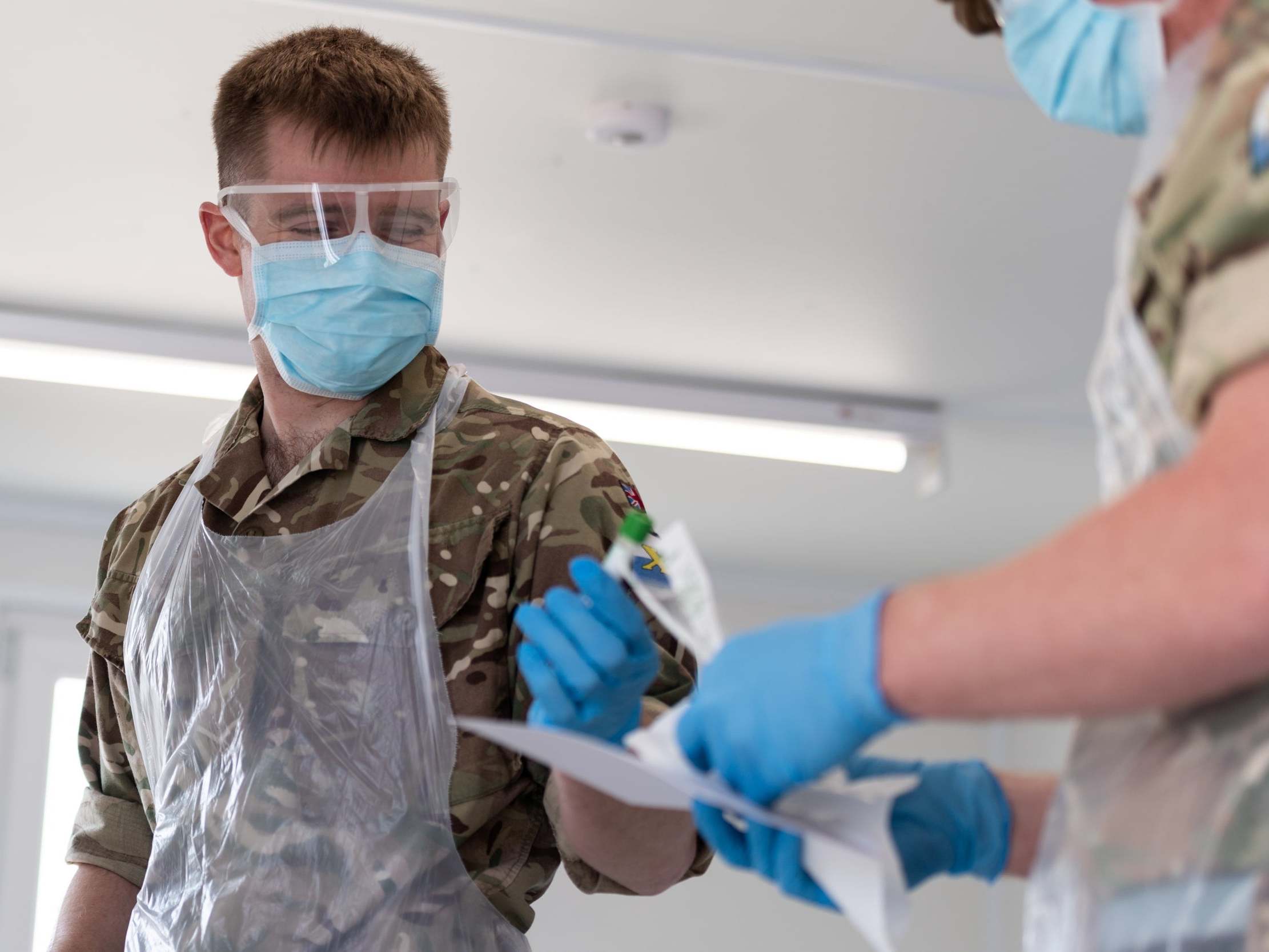

Scientists pulled in to analyse dry swab samples simply don’t have enough work to do. Over the weekend a laboratory technician anonymously wrote about the reality of the system’s unused human capacity. “Our shifts were meant to be excruciating, 12-hour marathons. In reality, they are rather more like laid-back morning jogs,” the scientist wrote. Dozens of academics and laboratory personnel from all over the UK languish in a hotel with nothing to do.”

The official I spoke to at PHE, which answers directly to the Heath Secretary, told me on 14 April that the government was on course to miss its target “by a wide margin”. “The management of the testing hubs leaves a lot to be desired,” the PHE offical explained. “Austerity and incompetence at the top means that we were just not prepared for this.”

The PHE official said that the government’s strategy is to centralise testing around 29 regional drive-in test centres across the country, where symptomatic key workers are swabbed. “The problem is with the rapid centralisation,” he explained. “A lot of this could be done at home,” he explained. “All you need is to put a dry swab down the back of the throat, package it up and send it directly to the labs. The logistics of setting up hubs is inherently prone to teething problems and we simply don’t have the time for that.”

East London is served by an Ikea store and facilities set up at the O2 Arena in Greenwich and Stansted airport. I spoke to two doctors displaying Covid-like symptoms who were told by PHE to report to the O2 Arena to be swabbed and tested. On arrival they were told they were not on the list and left without being tested. Days later Hancock appeared to blame NHS staff themselves for the government’s failures. “Staff haven’t wanted to come forward,” he said. “Frankly, the number of NHS staff coming forward wasn’t as high as expected.”

The government’s strategy has failed on its own terms and has imperilled public health in Britain. Reports have emerged that Johnson’s administration ignored scientific consensus to test early. Minister’s mantra that “At all times we have been consistently guided by scientific advice to protect lives” appears to be an alibi for its failure to exercise good judgement on the basis of the scientific briefings it received.

Scientific advice on something as complex as how to protect a population of tens of millions of people against a pandemic unprecedented in at least a century, will vary. What is however not in dispute is that the course the government chose to chart, or chose not to chart, has led us to a place of lesser safety.

How we arrived here, however, is not only a story of specific botched decisions over the past few months. The explanation is simpler. Our unhappy destination is at least equally the result of a decade rate of slowing growth in funding settlements between the Treasury and the NHS, which has created a widened gap between budgets and the demands of a growing and ageing population. Pandemic planning has been only one of the casualties of austerity. It is no exaggeration to say that many of us are now paying with our lives.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments