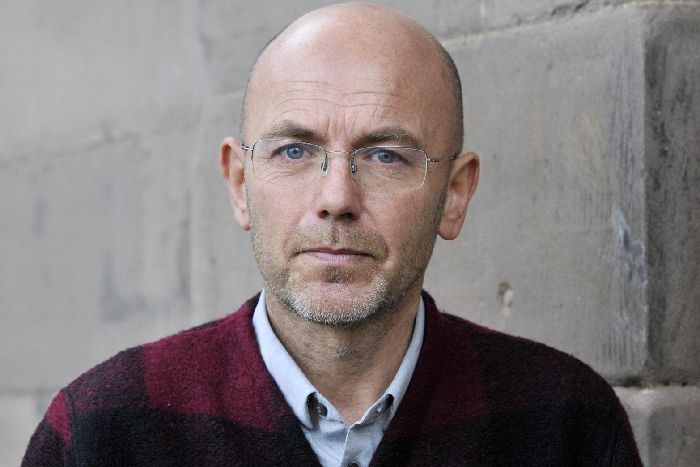

‘They’ll design almost anything’: Wayne Hemingway on how his working-class DIY roots helped him in fashion

Award-winning designer Wayne Hemingway speaks to Andy Martin about finding redemption with Red or Dead

Have you ever had anyone tell you: “You’ll never amount to anything in life”? Don’t worry about it. Wayne Hemingway’s harsh and short-tenured stepdad told him exactly that after a poor school report. His attitude was, “I’m going to prove him wrong!” Which worked out well, considering he – in collaboration with his wife Gerardine – set up Red or Dead and Hemingway Design.

His father was Billy Two Rivers (his real name), a professional wrestler and a Mohawk chief. His mum worked for the Post Office by day and was a croupier by night, but “her whole life revolved around fashion and music”. His grandad was a miner in Grimethorpe Colliery and his grandma was a cleaner. Says Hemingway: “You can’t get more working-class than that.” When he was growing up, his grandad would make him toys and his mother would make all their clothes. So there was a great tradition of DIY in his family.

He won a scholarship to Queen Elizabeth Grammar School in Blackburn, where he redoubled his efforts after the provocation of his stepdad. “It’s my firm belief, nobody is born with talent – but you can work for it,” says Hemingway. He compares himself with the young David Beckham who would not go to bed at night before he had kicked a ball through a tyre a hundred times.

He might have gone to Oxford or Cambridge but he chose to study at UCL. “I went to London rather than London University,” he says. He didn’t attend lectures that much.

“It was all about clubbing and dancing and music.” Hemingway had been pulling all-nighters since the age of 13. “I had total freedom,” he says. “My mum never stopped me from doing anything.” He says the average age at the clubs he used to go to in the 1970s was around 15 or 16. “Back then you didn’t need ID.”

He met his future wife Gerardine at a northern soul club, Angels in Burnley, one Wednesday night in 1981. “I spotted her amazing outfit,” he says. “I’d never seen anyone as well dressed as her.” He still has the ticket with her phone number, in her handwriting. “We were only kids,” says Hemingway. Four decades later they’re still together.

She left school aged 15 with no qualifications, determined to make it in the fashion business. He had formed a band in London, but to fund it they sold clothes in Camden and Kensington markets – some were second-hand cast-offs (aka “vintage”) and others had been run up by Gerardine on her own sewing machine. They paid £6 to rent the stall and made £80 on the first day. Soon the clothes business outstripped the music business. And Red or Dead was born.

It’s always been teamwork, says Hemingway. “I don’t think either of us would have achieved what we’ve done without the other.” Her style was “Russian peasant, rough-and-ready, with frayed edges and sackcloth”. But it was a “clubby” look, says Hemingway. He found himself doing a degree in geography and town planning, and still going out clubbing three or four nights a week, while also opening 16 outlets across London. “It seemed normal at the time. It was an adventure.”

By their mid-twenties, the Hemingways had several kids and 23 shops scattered around the country. “It still didn’t feel like a proper business. We had no training and no background in business. We were just having fun. I remember we were at a show in Paris and it felt like, wow, this is great! Who’d have thought we’d ever be in Paris? There was no chance to stop and think, we’re out of our depth!”

Red or Dead managed to combine fashion, music and political statement in a T-shirt or a pair of shoes. The Hemingways had a whole collection made in prison. They collaborated with Greenpeace. They distributed leaflets. They got involved in Rock Against Racism and protests against the Poll Tax.

“None of it was done cynically,” says Hemingway. “We were in London and we reflected the student protests. We were almost still students ourselves. We became the voice of that generation. It was the best marketing you could have, but we didn’t think of it like that. It’s not something you can manufacture.”

They are also spearheading the annual Good Business Festival, with the emphasis on ethical capitalism

Camden, in the mid-1980s, was like a microcosm of the zeitgeist. “Everything aligned,” says Hemingway. Post-punk gave way to the acid house era. Or as Hemingway neatly puts it: “The marching stopped and the mass dancing began.” Red or Dead took off and became the signature brand of the acid generation. “We were at the right place at the right time with the right attitude. But you had to have a good product too, or it wouldn’t have sold.”

They opened stores in Tokyo, Vancouver, Hong Kong and Copenhagen. There were queues outside the shops before they opened. “It’s hard to think of another fashion brand of the time that was as hot as we were,” says Hemingway. But they had no business plan. “We never did a spreadsheet. We didn’t have an overdraft. We didn’t have an accounts department. We had Doreen. And then Amrit. It was all organic and spontaneous. The demand was there and we were on a roll. And my mum managed a factory up north.”

Hemingway reckons that his wife was the tough one and more highly driven, going straight back to work within days of giving birth. “We were the first in our families to be wealthy,” he says. They sold the company in 1998 when they felt they’d had enough of the fashion industry. “There were a lot of tears. But we were still young and I felt I wanted to do something different with my life.”

Hemingway was still in his thirties. He couldn’t imagine that he would still be doing it in his fifties. “Fashion is a relentless treadmill. We have some regrets. We could have gone on. But I was increasingly getting angry with things that were happening in the world. I thought there were other things we could do.” And so Hemingway Design was born.

Hemingway wrote an article for The Independent in 1998, bidding farewell to Cool Britannia and heaping scorn on the then Blair government for only pretending to represent youth culture. He also got involved in heated debates on Newsnight. And one of the things he was angry about was the housing industry. He denounced the “Wimpeyfication” and “Barrattification” of Britain. Then one day George Wimpey phoned him up. They ended up collaborating on the Staiths South Bank project in Gateshead – affordable but stylish housing built by Wimpey with the Hemingways doing the design.

Now, garlanded with awards and doctorates and professorships, they’ll design almost anything, from carparks to tech parks to the regeneration of Scarborough harbour, and they have a separate arm, Hemingway Digital, concentrating on branding. But they are also spearheading the annual Good Business Festival, with the emphasis on ethical capitalism. Hemingway admits that the 2020 event in October was “crazily difficult, but it worked”. Its tagline is Profit Comes from Purpose. “This is the first generation to be poorer than their parents,” says Hemingway. “They demand more out of business. They demand better. We want to build something enormous, that will have the influence of Davos – but without the hypocrisy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments