Long waits and high fares: what is going on with Uber?

Company that promised to disrupt the minicab business is now beset by long wait times and higher fares after thousands of drivers left the trade during the pandemic, writes Ben Chapman

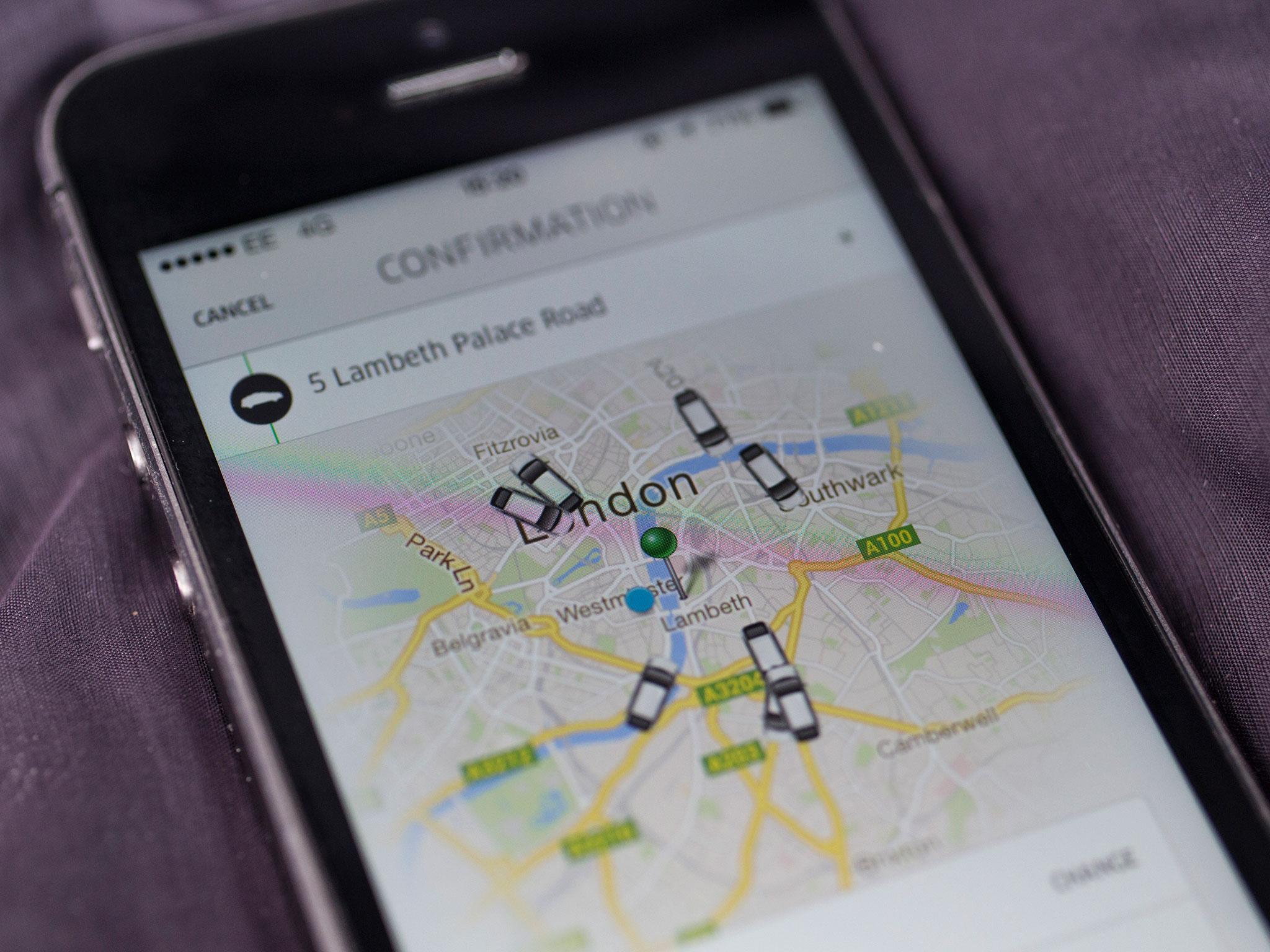

Uber once promised it would be “everyone’s private driver”, a revolutionary app that allowed passengers to hail a cab within a couple of minutes at the click of the button.

In the post-pandemic world, the dream of an affordable chauffeur service for the masses looks increasingly detached from reality.

Customers report that waiting times are much longer and fares much higher than before. Uber says this is nothing to worry about, it’s just dealing with higher demand and normal service will soon be resumed.

For its critics, the latest problems are further evidence that the Uber model is not sustainable. It cannot offer the low prices and convenience that have fuelled its rapid growth while also complying with the law and paying drivers an adequate wage.

So what exactly is going wrong for the controversial minicab app?

You might have expected that, as streets begin to hum with traffic, bars reawaken and town centres buzz again on Friday nights, we would be entering boom time for Uber – it might even turn a profit.

But the pandemic has been extremely tough on taxi and minicab drivers. Many say they were already fed up with their take-home pay being relentlessly driven down. Covid has further highlighted the insecurity and danger inherent in the job.

Driving a taxi or private hire vehicle in the UK has been the most dangerous of all professions, with a higher percentage of Covid deaths than any other. Meanwhile, earnings dried up.

The effect has been dramatic. After steadily rising in the years since apps started dominating the minicab trade, driver numbers dropped precipitously, by almost 16 per cent, between 2020 and 2021.

To put it another way: almost one in six licensed vehicles were taken off the roads in a single year. Separate figures for Uber aren’t available and the company did not respond to requests for comment.

There has understandably been a huge amount of focus on lorry drivers, but the taxi trade has seen an even sharper labour crunch.

Mehmet, an Uber driver in London, lost a close friend and fellow driver to Covid-19. Other colleagues got sick but made it through and decided to quit the business.

Some are training as lorry drivers, attracted by the reports of big bonuses, as well as the relative safety from the virus that life in the can of an 18-wheeler might provide. Others moved to delivery services such as Deliveroo and Getir or became couriers for Amazon.

Mehmet’s earnings have fallen dramatically but uncertainty is the biggest problem. “One week you might get £1,000 then the next week it’s nothing,” he says.

A Supreme Court decision ruling that Uber drivers were workers, not independent contractors, was supposed to herald a new era of security: guaranteed minimum wage, holiday pay and a pension.

But Uber has in some ways made things worse, say Mehmet and other drivers The Independent spoke to. The company introduced fixed-rate fares on some trips to replace fares calculated based on time and distance.

The move once again shifted risk from a huge multinational company on to the shoulders of its workers. A journey from Paddington Station to the East End of London might be guaranteed at £11, says Mehmet. That’s pretty enticing for a customer – a black cab might cost three times as much.

However, once Uber takes its 25 per cent (it used to take 15 per cent), the 45-minute journey pays little more than minimum wage. Then there are costs – all borne by the driver – such as insurance, maintenance, car finance and petrol, which have risen sharply while fares have fallen. If the fare is fixed, any delay during the trip is the driver’s risk.

Mehmet remains fearful of catching the virus himself but does not have the money to start his own business and, at 45, feels he is too old to retrain.

“Lorry driving, it’s a temporary shortage, you know,” he says. “Another three or four months [and] there will be more lorry drivers available everywhere.”

At that point, he believes wages will start to fall again, just as they have for Uber drivers in recent years. When he started driving minicabs in 2006, passengers were charged £1.75 per mile. Fifteen years later, the apps have decimated that. Uber charges £1.15 a mile. The drop in earnings has accelerated, he says. His earnings are down 35 per cent since before the pandemic. Other drivers cite similar falls.

Drivers report that their insurance premiums are double what they were a few years ago, while petrol has risen to a new record high. Drivers in London must also contend with the congestion charge.

As well as insecure earnings and uncertain costs, drivers must also live with the constant fear of having their licence revoked, often unfairly, says Yaseen Aslam, who leads the App Drivers and Couriers Union (ADCU).

He deals with cases “on a daily basis” where Uber has blocked a driver from using the app, and therefore cut off their earnings overnight.

In one recent case, a driver was wrongly accused of sexual harassment by a customer. After four weeks he was able to prove his innocence using CCTV footage but only after four weeks of no income.

“We do get a lot of drivers who we believe are completely innocent but it is very difficult to prove their case,” says Mr Aslam.

Other drivers have been “robo-fired” – sacked on the basis of a facial recognition algorithm used to ensure that they are at work and are not using substitutes to drive in their place.

Microsoft, which makes the software, has admitted that it is significantly less effective at recognising ethnic minority faces than white ones, but drivers have been sacked on the back of the questionable evidence. ADCU recently won a court case in the Netherlands which ruled drivers could not be terminated on the back of the algorithm’s evidence.

Uber is also being sued for discrimination in the UK by the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB) which has branded the software “racist”.

Mr Aslam says he is seeing more and more victories against Uber for unfair deduction of earnings. Now that the Supreme Court has ordered it to comply with the law and treat its drivers as workers, these cases are much easier to win.

Passengers may be unaware of all of the tribulations their drivers face, but they have had an effect on wait times and fares.

Thousands of cab drivers have left and aren’t coming back, says Mr Aslam. Those that have remained are becoming more selective about the journeys they accept.

“The bottom line is pay is unsustainable, it is much lower than it was,” he says.

“I see it from the customer’s point of view. They want it to be cheaper, but there is a human element that people are failing to see.”

Mr Aslam believes pay will need to rise 35 per cent to give drivers a decent wage and attract people back.

Uber has undoubtedly shifted people’s expectations of what they can expect from a cab service. The offer of an instant chauffeur at the touch of a button, for a price people could afford was, of course, very attractive to both customers and investors who have pumped in billions of dollars.

But, as Uber faces up to its legal responsibilities, its costs are rising and the company is still struggling to make a profit.

An unanswered question still hangs over Uber: Was its promise ever really attainable or was it all too good to be true?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments