Trump’s actions over coronavirus treatment put the whole world at risk

If countries tear up intellectual property rights in response to America’s cornering the market for a proven treatment, it could call into question future drug development. But you can hardly blame them, writes James Moore

You do sometimes wonder whether Donald Trump sits in his PJs and, after he’s finished his nightly Twitter rant, says to himself: “I wonder how I can screw up the world tomorrow.”

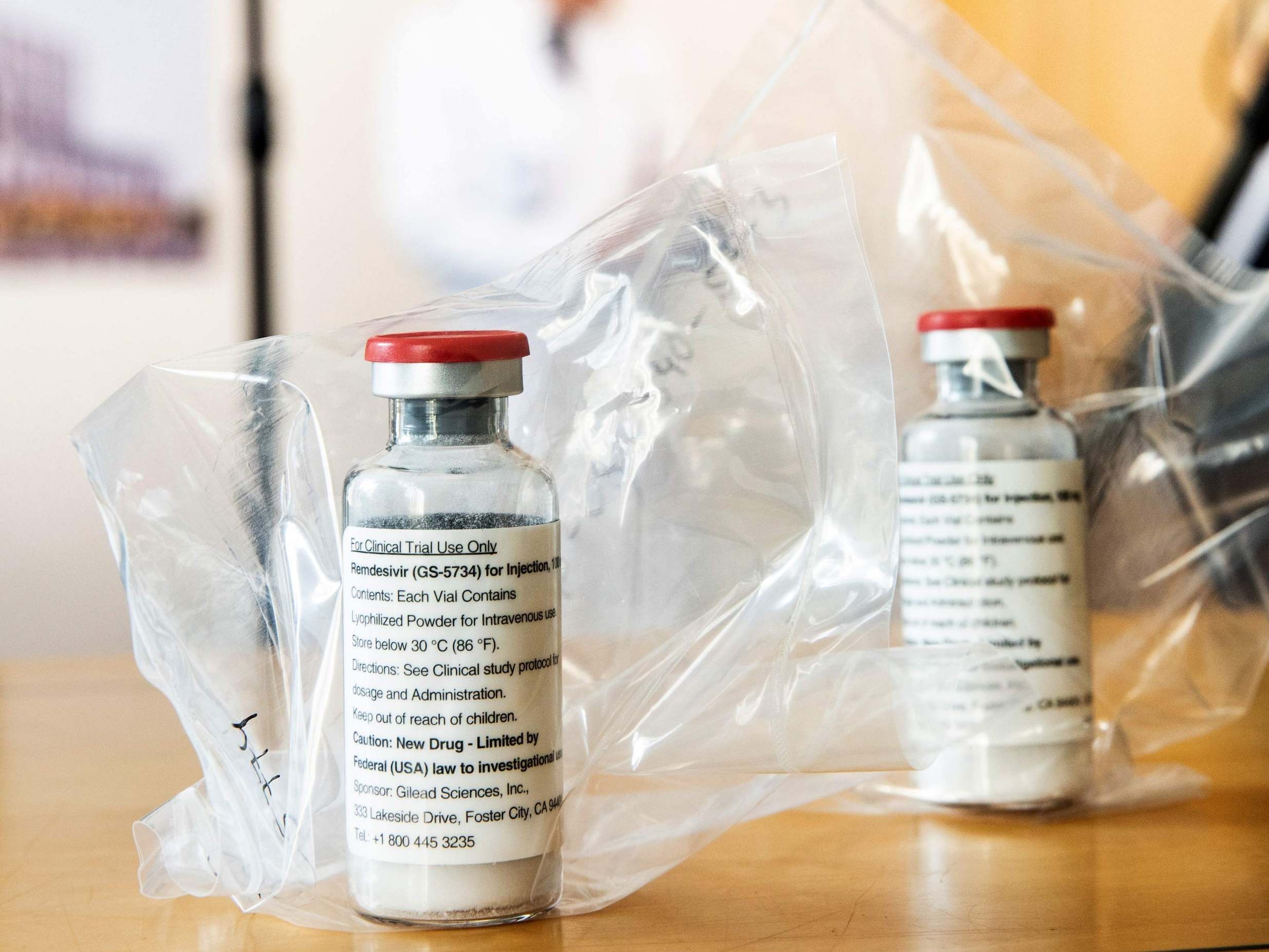

When it comes to coronavirus he’s found what the Americans would describe as “a doozy”. It has emerged that the US is gobbling up the world stock of remdesivir, a relative rarity in the pharmaceutical world in that it can have a beneficial impact on Covid-19 and is licensed for treatment. The US Department of Health and Human Services says its secured 500,000 doses, which accounts for all of July’s production and 90 per cent of August and September’s.

America First!

The drug is made by a US pharma outfit called Gilead Sciences, a name which now seems slightly unfortunate. Those who’ve watched The Handmaid’s Tale, or better still read the Margaret Atwood book from which the TV show is adapted, will be aware that Gilead is the name adopted by the rulers of an America gone bad.

Happily for we Britons, I’m told by government sources that the UK has plenty, thanks very much, and any NHS patient in need of a dose will get one. Ditto the only other drug approved in the UK, a steroid called dexamethasone (The Department of Health and Social Care has announced that is has 200,000 doses of that one).

That such supplies are available is important. Professor Neil Ferguson, from Imperial College, who is a former government advisor, has said of the pandemic that “this is far from over”. It is a message we’re hearing a lot, with good reason. The local lockdown in Leicester, in addition to the spikes recorded in other areas, speak to that.

The drug in question can shorten the recovery time in some patients by up to four days. It’s not cheap: the cost is around £2,500 for six doses, although more than 100 lower or middle income companies will be able to get hold of it at a lower price (at such time stocks become available).

The cost has nonetheless caused some controversy. The company has defended it in an open letter on its website by pointing out that the costs of four days in hospital in the US are much higher.

Here, if it is able to free up NHS beds earlier, it could be invaluable. A stockpile is thus a handy thing to have.

So hooray for us! Britain First!

As for those parts of the world that aren’t so lucky at a time when production will be sent to one place? Hard lines.

But wait, there is a way for them to potentially get around this – by tearing up the patents and doing a deal with a generic manufacturer in a part of the world where they’re not recognised.

Many governments, including ours, have the power to do that. It’s not something the pharmaceutical industry is terribly happy about.

“Compulsory licensing – the seizure of new research – is not the answer and would completely undermine the system for developing new medicines, including those for the coronavirus,” I was told by Richard Torbett, the chief executive, of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry.

Meanwhile, Thomas Cueni, director general of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, argued in the FT that “risk taking would be impossible” without the protection of intellectual property via patients.

Their points are valid.

It’s not always easy to feel much, if any, sympathy for Big Pharma.

Drug pricing has caused controversy in part because of some decidedly shabby, and sometimes out and out sharp, practice at the industry’s rougher edges.

The Competition and Markets Authority has been very busy in the area, bringing several cases and proposing heavy fines.

Critics are apt to use the word “profiteering”, and sometimes justifiably.

But the point remains that research is risky, time consuming and expensive. New treatments only emerge through companies, and investors, rolling the dice. One of the reasons they are frequently expensive is because they have to subsidise failures.

Cueni argued that it is precisely because of the protection of intellectual property that the current international, collaborative effort to find effective treatments and vaccines is possible.

Torbett pointed me to commitments that “global companies have made” to ensuring affordable pricing and fair access to treatments and vaccines for Covid-19. “We expect them to live up to this commitment,” he said.

Some are doing that, working to licence production to third parties so, for example, nations will be able to access home produced stocks if and when one of the 120 vaccine projects strikes gold.

Vaccines, of course, typically require the oft used expression “herd immunity” to be truly effective. In other words, if one emerges it needs to be given to as many people as possible globally.

So these deals are very necessary.

But then you have Trump and America and a destructive and self-defeating ideology.

By its actions, it threatens to bring the house of cards crashing down.

It is cutting off its nose to spite its, and potentially Gilead’s, face because if it refuses to play fair you can hardly blame other countries for doing what it takes for their citizens. Even if that means setting fire to patents, with potentially damaging consequences when the next pandemic emerges. And one surely will.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments