How Tovertafel is using games to help people with dementia

The Alzheimer’s Society estimates that 850,000 people suffer from dementia in the UK, and so Tovertafel, an interactive game, was designed specifically for individuals with cognitive impairment, writes Martin Friel

Dementia has impacted the lives of most people in the UK in some way – be that as a sufferer, or as the family or friend of a sufferer. And despite the huge amount of research and effort that has gone into trying to tackle the condition, we are no nearer to finding a cure.

The Alzheimer’s Society estimates that 850,000 people suffer from dementia in the UK, and worryingly, they believe that figure will rise to 1.6 million by 2040. This year alone, they predict that nearly 210,000 people will develop dementia – that’s one person every three minutes.

And it is statistics like that, combined with the knowledge that there is no cure, and the fact that we are living longer and longer, that makes the threat of developing dementia feel like a particularly grim lottery to be played in our dotage.

Such is the nature of the condition, robbing people of the very thing that makes them human and with no hope of recovery, that the standard approach to treatment is to manage the decline of the individual; to make their lives as comfortable and stress-free as possible as the condition progresses to its inevitable end.

Which is depressing; but out of a desire to understand how dementia sufferers experience the world, and to make that experience less grim, a business has been born. More than that, its founder is seeking to bring social engagement and even some joy to the often closed-off world in which sufferers find themselves.

Read More:

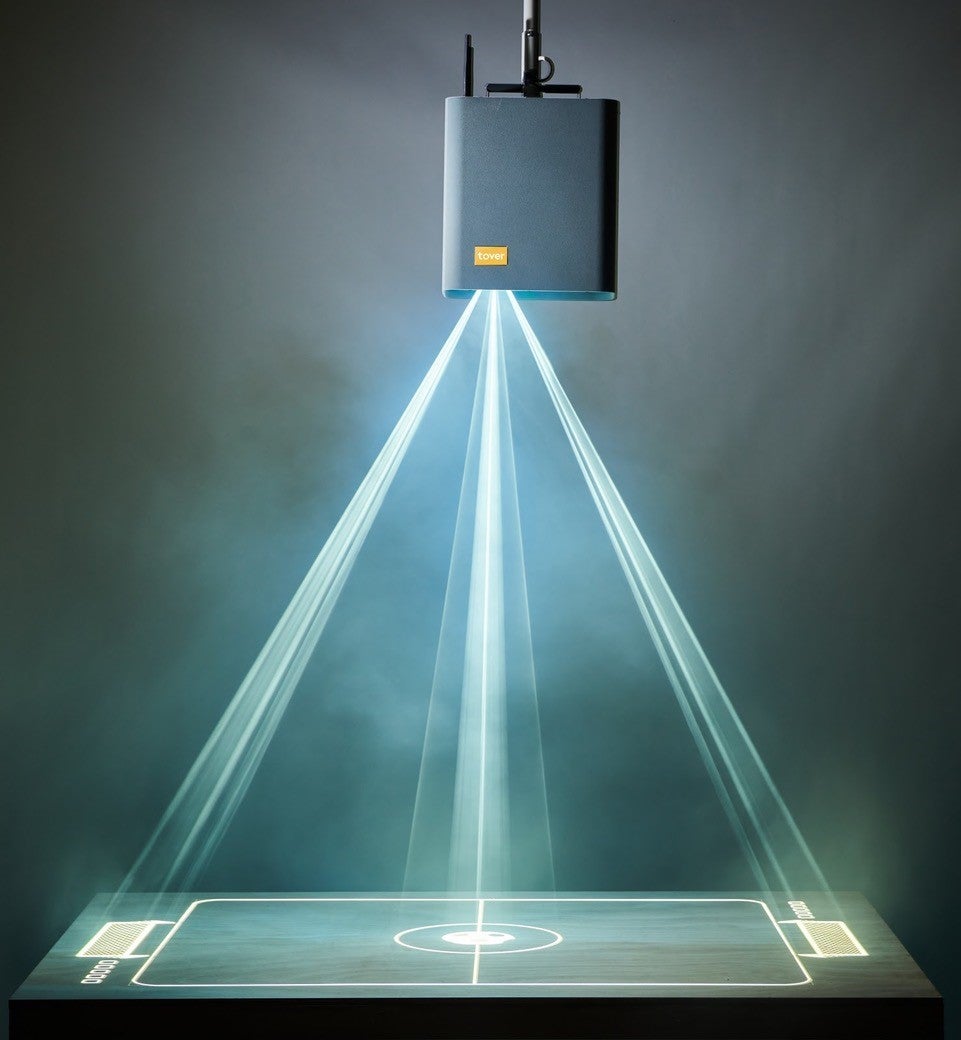

Hester Anderiesen Le Riche is the founder and CEO of Tovertafel (Dutch for ‘magic table’), an interactive game designed specifically for individuals with cognitive impairment. Essentially a light box that projects moving images on to a tabletop from a ceiling mount, Tovertafel hosts a range of interactive games that dementia patients can play individually or as part of a group.

They can use their hands to interact with a range of realistic scenarios, such as sweeping leaves, painting with colours, playing a game of marbles, or even playing with the fish and lilies found in a pond. It’s light years away from the static, restricted lives that many sufferers lead.

There are around 30 games available at the moment, covering a range of activities – all of which, crucially, are recognisable from the real world.

“It was all abstract designs to begin with, but people didn’t really engage, so we understood that the recognition [of the real world] was important,” says Le Riche.

“If you are more physically active you will be sweeping the leaves, or you can search for the ladybirds that are hiding under the leaves. If you don’t find them, that doesn’t mean you are doing it any worse,” she adds, explaining that one of the key features is that players can’t play the game incorrectly.

“In this stage of their lives, it makes a big difference, as what they are capable of surprises them – group playing, triggering memories that might start another conversation. They are so unfamiliar with that experience in this stage of their lives.”

The idea originated from Le Riche’s PhD project, which looked at how dementia sufferers experienced and interacted with the world.

“Most people that live with dementia in care homes sit still every day, and that has a bad effect on physical wellbeing and mental wellbeing. I wanted to develop something around play that would reduce apathy,” she says.

And that something is Tovertafel, which is now used in 14 countries worldwide and in 750 care homes in the UK.

“I feel strongly that we are not looking after certain groups in our society as well as we could. We have so much knowledge and resource in society, and products and tech services that enhance our lives, but there is very little used in the care of the oldest in society,” says Le Riche.

“When I designed the product, there was literally nothing else that used tech to improve their quality of life. Most products are focused on the care tasks, to make it easier – and they are amazing, but there’s more we can do to contribute to the experience of today.”

It is perhaps that approach, that starting point, that has seen Tovertafel embraced by patients and carers alike. Le Riche says that for all the trauma experienced within the care sector throughout the Covid pandemic, the last year has at least shone a light on conditions in care homes and the stress carers are under.

“The challenges have always been there,” she says, “but they became way more severe, which was heartbreaking, but it made it much more visible. Everyone knows the situation of the residents and the care workers now – their stress and fatigue.”

While the system and its games, which can be bought up-front or on a subscription basis, were initially designed with patients in mind, Le Riche found that there were positive knock-on effects for carers too. While patients are playing the game, they are occupied but safe, giving carers time to focus on other pressing tasks or even just to take a breather.

And such has been the enthusiasm for the system amongst carers, they now perform a key role in the ongoing development of the games.

“We have had several initiatives where carers would reveal their own tips [about using the system] with other carers, which gave them a sense of fulfilment too,” she says.

“We co-design everything we make – software, hardware and online training portals. We recently had a campaign where all the carers could hand in their ideas for new games, and we have an expert panel to select the ideas and bring them to life.”

Despite the growth of Tovertafel, Le Riche says that applying tech to help support the day-to-day experiences of dementia sufferers is still not seen as a core element of the care system.

“There is a trend towards more of this but it’s still in its infancy,” she says.

But there is, she believes, a certain inevitability that more and more organisations will seek to follow in Tovertafel’s footsteps.

Read More:

“The [incidence] of dementia is growing so fast that others are seeing a business model in this group because of the attention placed on it by society and governments,” she says.

“If there is a workable business model behind these kinds of products, it can only improve the sector.”

It may not be the cure that we all hope to see one day, but it is bringing back some humanity and dignity to sufferers, and perhaps reminds the rest of us that they aren’t just a shell of the human we used to know.

The joy, the curiosity and the need to engage is still in there – we, as a society, just need to focus our attention on helping to bring it back out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments