How flying Red Arrows taught Justin Hughes business acumen

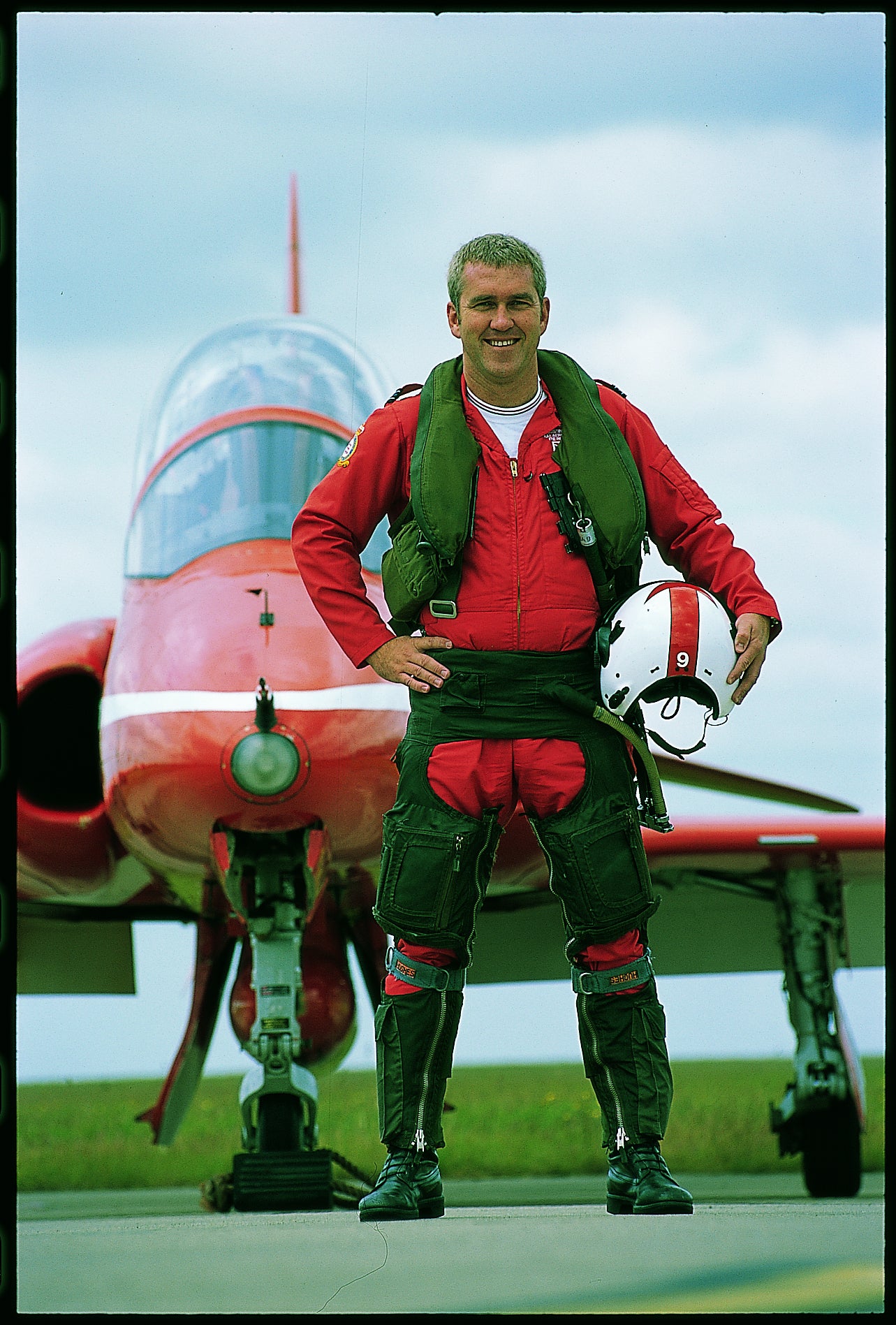

Retired Flight Lieutenant Justin Hughes sits down with Steve Boggan to share how flying Red Arrows taught him the secrets of the business world

When the scariest thing that has happened in your career is breaking a pencil at a press conference, asking Justin Hughes about his hairiest moments is a humbling experience.

“There was the time I was simulating combat against a Dutch F-16 fighter at night, in the dark, at 600mph, 1,000ft above the North Sea, and one of my engines blew up,” he says.

I gulp.

“And there was the day I was in tight formation with the Red Arrows team and we flew into dangerously dense cloud and suddenly couldn’t see each other. You can fly in formation through cloud, but this was unusually bad and I was disorientated, and so were the other pilots. I couldn’t fly up because we were underneath Gatwick’s flight path, and there were eight other Hawk jets in the team somewhere close by and I was quite keen not to crash into them.”

Blimey, I say.

“But possibly the most dangerous incident was when my brakes failed at the end of a Red Arrows display as all nine of us came in to land. I overshot the runway at some speed and was hurtling across a field. I probably should have ejected then, but at the time I somehow felt safer inside the cockpit.”

Meeting Hughes (Flight Lieutenant, ret.), 55, is like being in the presence of one of your heroes, and that can render you a little bit speechless. As an RAF Tornado F3 fighter pilot, his job was to defend UK air space and, later, as executive officer of the Red Arrows, it was to thrill, amaze and instil in Brits the proud sense that while we may not always have the best kit in the world, we will always have the best pilots.

Hughes is managing director of Mission Excellence, a company devoted to improving the performance of businesses, organisations and individuals by taking the skills he learned in the Red Arrows and RAF – skills of teamwork, meticulous planning, risk assessment, high performance in stressful situations, perfect mission execution and learning from mistakes and near-misses – and taking them from the cockpit and into the workplace.

The speed and precision just blew me away. Afterwards, the pilot asked whether I had ever applied to join the Red Arrows and I said I hadn’t

Clients who take advantage of Mission Excellence courses or workshops, or who use Hughes or other of his former fighter-pilot colleagues in-house to help turn around their failing operations, often speak gushingly about being changed for the better. You could call it inspirational teaching, but with wings.

“It took me a while after leaving the RAF to realise how many of the skills I learned there could benefit companies and organisations – and how many of these skills were lacking in so many workplaces,” says Hughes. “To me, after 12 years of training and performing in high-speed, high-risk environments, they came naturally, but sharing them with others has been a wonderful and very rewarding experience.”

Among those Hughes and his colleagues have inspired – and changed – are Nato, Microsoft, the United Nations, the Mercedes Formula One team and BP. It is an impressive portfolio.

Born in Billinge, near Wigan, to Des, a mechanical engineer, and Brenda, a school teacher, Hughes promised himself at the age of “seven or eight” that he would one day be a fighter pilot when his father took him to the Farnborough air show… and he saw the Red Arrows.

“There was absolutely no one in my family with connections to the military or aviation, but for reasons I can’t explain, I always wanted to fly – it was in my DNA,” he says. “Back in the days when you were allowed into the cockpit, whenever we went on holiday I would always be the geeky kid asking the flight crew what this button did or what that light was for.”

After leaving school, he joined the army for a year before going to Bristol University to study physics. There, during freshers’ week, he saw a stand offering the chance to sign up for the University Air Squadron, which was sponsored by the RAF.

“I thought I’d had my fill of the military after my year in the army, but if you joined up, you got free flying lessons, and I just couldn’t resist,” he says.

After taking a year to travel, Hughes joined the RAF in 1990 at the age of 23 as a general duties officer, but with his eye on becoming a fighter pilot. Three years of training followed, first on Jet Provost training aircraft, then moving on to the more advanced Hawk fighter, after which he was awarded his wings, and then went on to the frontline Tornado F3.

For six years he was stationed at RAF Leuchars in Scotland with 43 Squadron and 111 Squadron. There, he and his fellow pilots patrolled the waters around the UK as its first line of defence against any would-be aggressor.

“We trained, trained and trained for every eventuality, and we took part in exercises defending against simulated threats,” he says. “We had an expression in the RAF – ‘Train Hard and Fight Easy’.”

Hughes’ period in the service came between both Iraq wars and before UK forces were deployed in Afghanistan, so he was never called upon to fly combat missions, though he did serve in Bosnia to police the no-fly zone imposed by Nato to halt Serbian aggression, and that wasn’t without risk; Serb surface-to-air missiles shot down several Nato aircraft.

In 1997, while training in Cyprus, Hughes met the Red Arrows team, who were at RAF Akrotiri preparing for the display season. One of the pilots offered to take him up in a two-seater Hawk, the unit’s aircraft of choice, and he was amazed.

“It was eye-watering,” he says. “The speed and precision just blew me away. Afterwards, the pilot asked whether I had ever applied to join the Red Arrows and I said I hadn’t. I think to most pilots, the Red Arrows are seen as elite and aspirational, but I didn't think I could do it.”

But he was wrong. He applied and made a shortlist of nine in 1998, although he wasn’t one of three chosen. The following year, he applied again and was accepted. By the time he left the RAF in 2002, he was the team’s Executive Officer, effectively the second in command.

So, if he had to choose one facet of RAF life that most benefits his clients, what would it be?

“Debriefing,” he says. “Organisations have structures and plans and strategy, but I’ve found that they don’t practise debriefing enough. So, where there have been mistakes or shortcomings or examples of poor performance, people in those organisations don’t discuss them enough afterwards, and that means they don’t learn from them.

“If there is one thing that makes a real change when I describe it, it’s the power of learning from debriefing exercises. I explain that this is what a high-performance culture does, it learns from its mistakes, and how performance can improve from that. And when people realise that they’re not doing it right, or not doing it at all, it’s like a light coming on.”

So, if you’re in business but feel like you’re flying by the seat of your pants, perhaps give Hughes a call. He’d be happy to be your wing man.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments