Music rights deals are booming and that looks set to continue

With tours on hiatus, musicians are looking for new ways to make cash, writes James Moore

Has music’s multimillion-dollar back catalogue money-go-round started to slow?

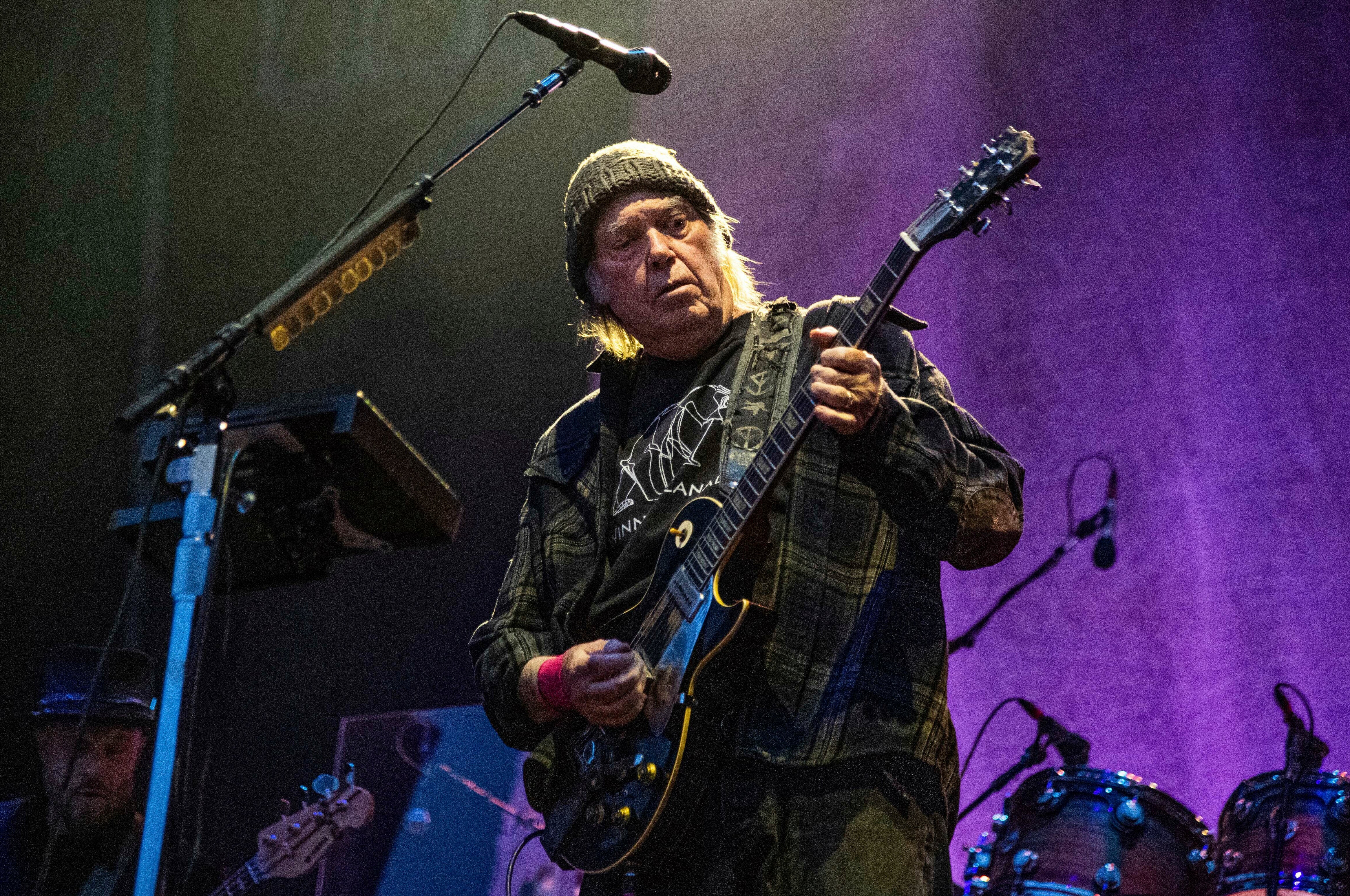

The London-listed Hipgnosis Songs Fund started the new year with a blast, spending an estimated $150m (£108m) for a 50 per cent stake in the rights to 1,180 songs written by Neil Young. Hipgnosis also struck deals with Shakira, Fleetwood Mac guitarist Lindsey Buckingham and producer Jimmy Iovine.

With money-spinning tours on hiatus, deals like these enjoyed a mini-boom in 2020.

But the fact that the man who sang, “Ain’t singin’ for Pepsi / Ain’t singin’ for Coke / I don’t sing for nobody / Makes me look like a joke,” had joined the licensing party still said something.

Given the potential revenues, you can hardly blame Young for, as Eric B and Rakim famously put it, getting “paid in full”.

Then something strange happened. Amid the blaze of publicity, the fund, set up by Elton John’s former manager Merck Mercuriadis, went to the market in search of up to £605m to fund more deals, and signalled that further capital raising would follow over the coming year.

The result was announced at 4.23pm on Friday 5 February – a time when the markets and most of the financial media have their eyes on the weekend. That is not the time you’d normally choose to announce what Hipgnosis described as a “successful fundraise”. Perhaps it was because the gross proceeds amounted to just £75m.

Could the Young deal represent a high watermark, the beginning of the end of a gold rush that has seen hit songs treated like gold or silver or oil, or any other commodity, because of the long tail of revenues they offer investors?

Maybe not. At the core of this trend is the idea that the rights to these songs have been undervalued in the light of the revenue opportunity that currently exists.

Paul Sampson, the CEO and co-founder of Lickd, has an interesting perspective on this. His business was set up to provide YouTube creators with a mechanism to legally access hit songs for use in their videos. He has been busily signing deals with labels and publishers – including Warner Music Group and Universal – which have released millions of songs for them to use for a fee.

The Universal tie-up is particularly noteworthy because of its involvement in another deal. It bought Bob Dylan’s entire catalogue of 600 songs for an estimated $300m at the end of last year.

The deal was similar to those pursued by Hipgnosis and other start-ups such as Primary Wave and Round Hill. Their aim is to sweat the assets they buy through growing the licensing revenues generated by hit songs. That Universal, a major publisher, was following these nimble, new(ish) kids on the block caught the eye.

Sampson argues that the potential revenues from licensing music online for use in user-generated content (UGC) put up on on the likes of YouTube are huge.

He points to a MIDiA Research report entitled The Rising Power Of UGC which estimated that in 2019 it contributed more than $1bn to global music revenues. The report suggested that music-related UGC revenue would total $4bn in 2020, including $2.2bn for music rights holders.

There are many other avenues that can be pursued on top of that and the more traditional ads and streaming revenues. Games, for example.

This explains the deals, as artists seek to cash in at a time when the revenues from those money-spinning tours are denied them.

The problem with the Hipgnosis cash call may have been caused by criticism directed at the fund’s perceived lack of transparency. Most of the time it hasn’t put figures on its deals, leading to questions about how it is valuing songs.

A critical note was published by Investec, comparing Hipgnosis unfavourably with Round Hill.

Get it wrong and investors in these funds will, obviously, get hurt.

On the other hand, price too low and artists could get huffy. A contract is a contract, but artists have the means to make life difficult for their business partners if they feel unfairly treated. Just look at Taylor Swift, who has been rerecording and rereleasing her albums after her label was bought by music industry mogul Scooter Braun and then sold on to an investment fund.

The row doesn’t involve the publishing rights, just the masters. But it does demonstrate a potential pitfall out there.

A partnership approach, as Hipgnosis has with Young, would seem wise when it comes to future deals.

Even if the fund’s cash call was a disappointment, there will be more deals, because in the midst of an economic crisis of historic proportions, hit songs and sweet music can still make sweet moolah. And lots of it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments