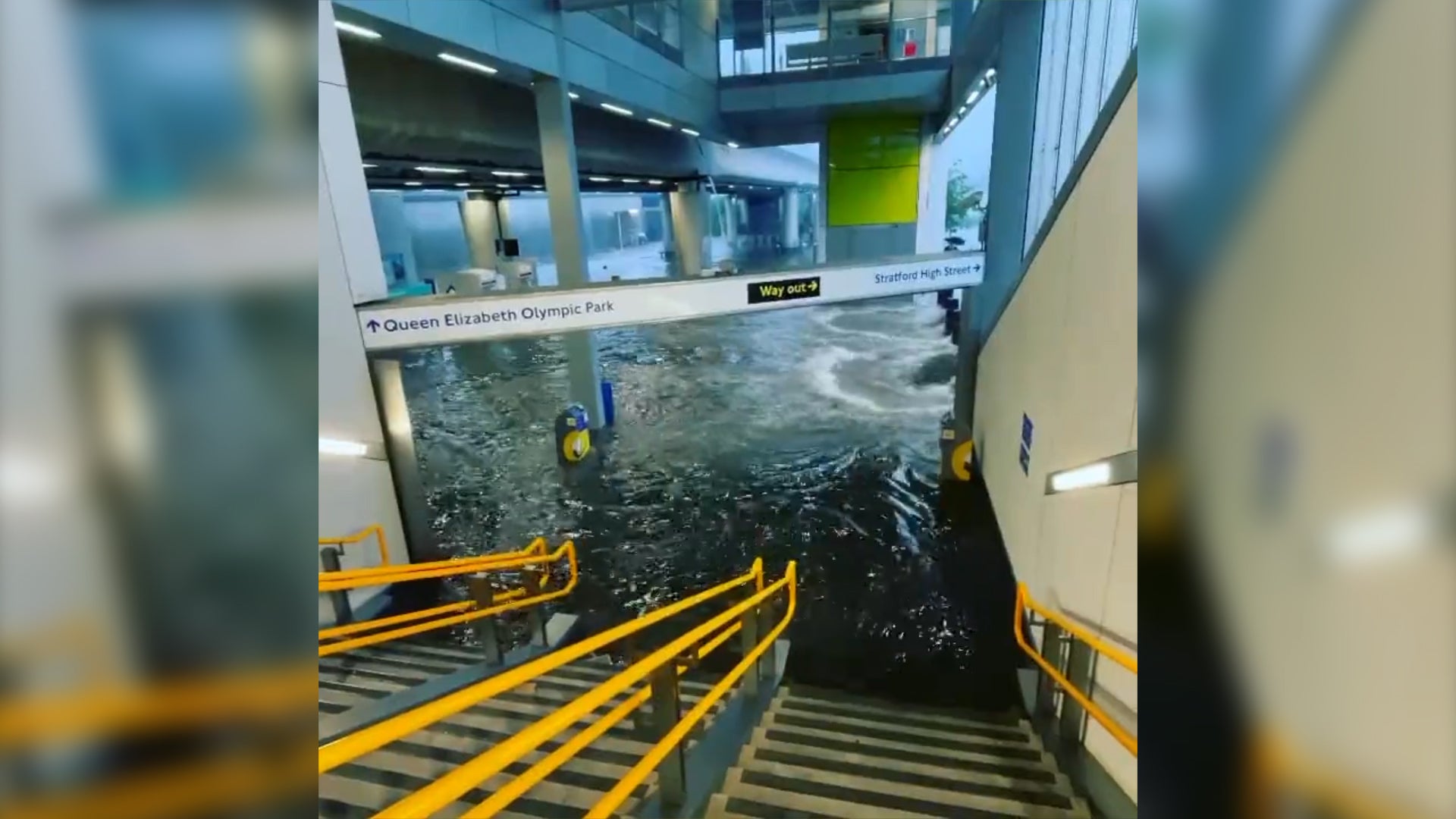

London floods again highlight economic cost of allowing the planet to burn

The government needs to find a way of stimulating more green investment. Reforming the solvency rules governing insurers could help so long as consumer protection is maintained, writes James Moore

“For the UK, the most tangible evidence [of climate change] is severe flooding.”

That’s not my view. It comes from the insurance industry, the claims side of which was having a busy day on Monday in the aftermath of the flash floods in London that closed roads and, more seriously, led to the declaration of a major incident by Barts NHS Trust after problems at two of its hospitals.

Extreme weather events such as the one the capital experienced – with more than a month’s rainfall tipping down in the space of a couple of hours – are set to become much more common the hotter the planet gets.

They emphasise the need for urgent action, not least because the economic costs we’ve so far incurred represent little more than a trailer when one considers the disaster movie that’s coming.

An entirely more welcome story, however, on that subject also emerged over the weekend. It was the announcement by Fidelity, a US fund manager that oversees $787bn (£569bn) in client assets, of plans to punish directors at more than 1,000 firms globally if they fail to address the issue.

US money managers have been climate laggards when compared with their UK and European peers, which have taken a more assertive approach – both behind the scenes and in public, with their votes and (sometimes) their investment decisions – towards the companies in which they invest.

They were far quicker to recognise that the climate crisis is bad for business. Its most obvious victims are insurers, which will inevitably be dealing with a higher incidence of claims, such as the ones now being filed in London. They are expected to increase over the next few days.

But the economic blowback from events like this, and the yet worse disasters in Germany (flooding) and the western part of North America (wildfires), happening more often will be felt across the board by multiple industries.

There are nonetheless a large number of companies that still prefer to make like the proverbial ostrich that responds to danger by sticking its head in the sand.

Some of those heads need yanking out. If that means making some high-paid company directors feel the heat, then so be it.

The same is true of those that see the problem but think they can respond to it with a little greenwashing.

But Fidelity’s move is only a step in the right direction at a time when we really ought to be running, not walking.

Another one of those could come courtesy of the British government, which is looking at reforming the Solvency 2 regulations governing the insurance industry.

The idea of a Brexit dividend is a myth. The best way of tackling the climate crisis would be to reverse leaving the EU, because the economic gains from doing so would be formidable and so would the investment that could be deployed through them.

Unfortunately, that’s a pipe dream right now. Looking at reforming some of the less attractive of the EU’s rules is small consolation. It counts as making the best of a bad job. But reforming this one could deliver a dividend if it were to facilitate the deployment of some of the industry’s vast balance sheet towards green investment.

Any such reform, which is currently being explored, would obviously need to ensure adequate consumer protection. It would also need to be structured to prevent the industry from indulging in a splurge of special dividends and share buybacks. That wouldn’t help anyone.

But there is potential there, and a lot of it. The numbers could be very large.

The final issue that this latest incidence of flooding highlights is the need for enhancing the UK’s flood resilience – a drum the Association of British Insurers has been (correctly) beating for years.

Flood Re, the state-backed reinsurer, currently provides flood cover for hundreds of thousands of at-risk homes built before 2009.

It’s due to be with us until 2039, so quite some time, but you wouldn’t want to bet against that being extended. Successive chancellors have tended to focus on the costs of improving flood defences as opposed to the value.

There is also a real danger that the government’s attempts to increase the number of new homes being built leads to backsliding on, for example, building on flood plains.

So it isn’t just fund managers and the private sector that have to take the climate crisis a lot more seriously than at present.

Nature seems intent on ramming the point home and will doubtless do so again before too long, probably with a deal more ferocity than what London experienced over the weekend.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments