We’ve learnt what our parents knew – that our whole world can come crashing down

We supposed we were secure and we’re not. And like the generations before us who dealt with war and the Great Depression, says Chris Blackhurst, we will emerge from this crisis less wasteful and more risk-averse

Growing up, I never understood why my parents were so cautious where money was concerned.

We never had much anyway, but even so, they were reluctant to splash out or, heaven forfend, take out big loans or run up credit card bills. They regarded my spending habits with horror. They moved house rarely, clothes were bought to last, they would get three meals out of one chicken.

I put it down to their parents’ generation. We would visit relatives’ houses, my sister and I, and sit in often drab sitting rooms, frequently with a black and white picture of a young man in uniform on the mantelpiece. He was a cousin, a son, who never came back.

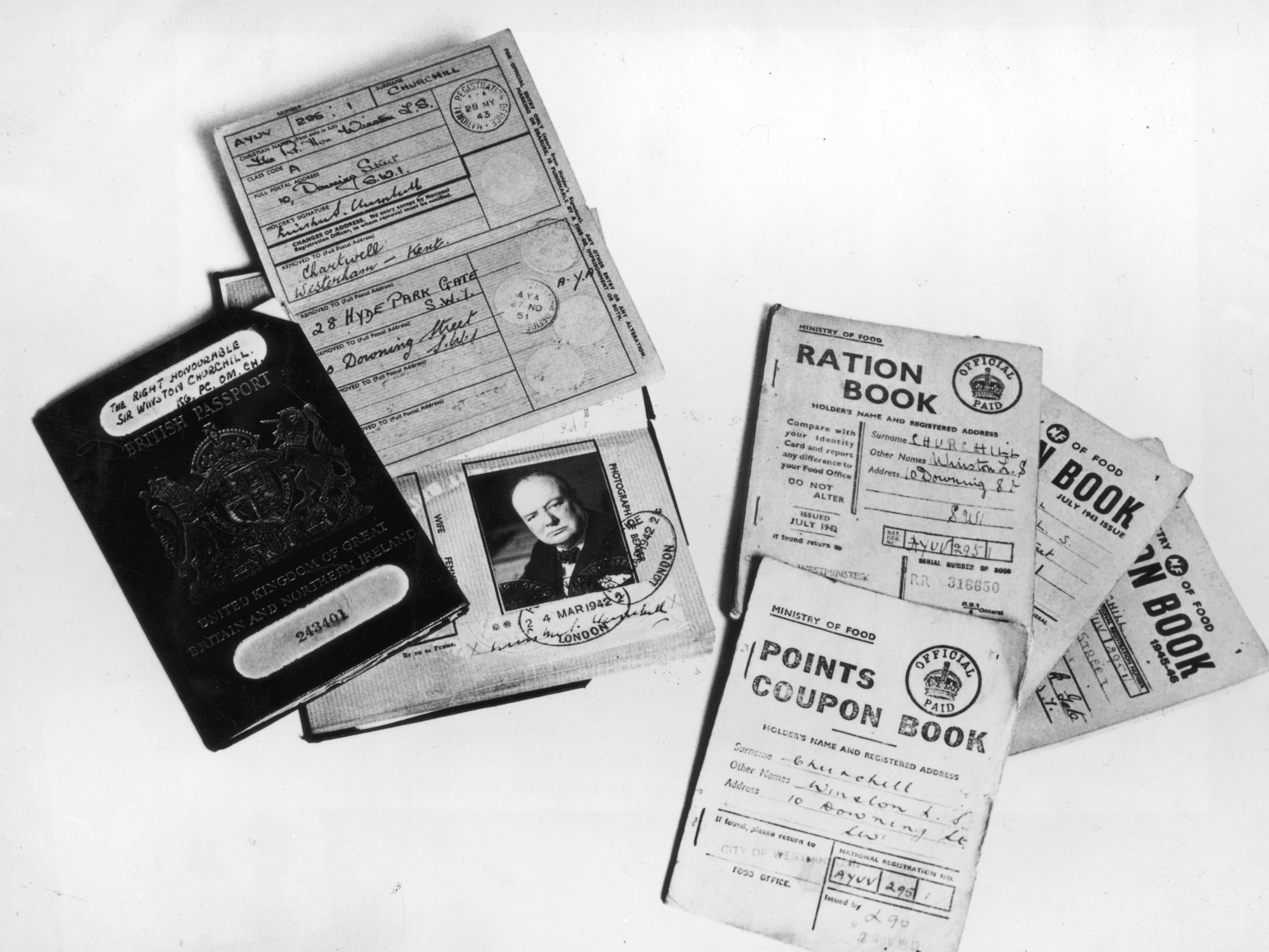

The war was to blame. They’d had it tough during those years and afterwards. Cash was tight, and there’d been rationing.

Even so, I admit, I never really questioned why they should be so conservative, especially when the banks seemed to be falling over themselves to lend. They had safe jobs as teachers. Although again, I did not really appreciate why they were so keen to work in the public sector; why, when discussions turned to career prospects, they always thought first about some aspect of the government service.

That was true as well of their regard for pensions and savings. Constantly, they cited the need to put money aside for the future.

Now I know what lay behind their hesitancy. It was the Second World War alright, and them hearing tales of the first great conflict, and the depression in between. They knew how, in one instant, the world could change, how everything could come crashing down.

We never got that. We enjoyed ourselves, partied like there was no tomorrow, amassed debts, went crazy for material must-haves. We were not aware what could happen; we were not in the least bit bothered.

There were crises, of course there were. The banking crash of 2008, the bursting of the dot.com bubble, recessions and national slowdowns and strikes. Their impact, though, was not totally scarring. Some people lost their jobs, some businesses went under. But by and large, the damage was confined to one section of society. We were taught too, to think in cycles, that markets would go down after being up, and then go back up again.

Likewise, there had been terrible occurrences – 9/11, the Asian tsunami, famines, droughts and earthquakes. But they were localised, not universal.

We supposed we were secure and we’re not. And no amount of personal wealth or possessions would have protected us. We’re all in this together and no one is immune, no economy is untouched

What we did not realise was just how quickly things could shatter, how everyone would be affected, and how the harm would be all-encompassing. We’d never had a 3 September 1939. On that day, Britain declared war on Germany. France followed suit, and the Second World War had begun.

Beforehand, people were afraid that confrontation might be coming. But they went about their ordinary lives. Then came the sonorous announcement at 11am and their world was tipped upside down.

I am not saying the battle against corona will be as long-lasting as the war. Hopefully, it will be over in short order, in a matter of months versus six years.

Nevertheless, we’ve experienced a profound shock. We’ve suddenly been made to understand that nothing is safe, nothing is guaranteed. We all know that bad stuff can happen to us as individuals, that we can be victims of crime or an accident or illness at any time or a business can go under. But this is something that affects all of us, at once.

We supposed we were secure and we’re not. And no amount of personal wealth or possessions would have protected us. We’re all in this together and no one is immune, no economy is untouched, no organisation, no enterprise is ring-fenced.

What does it mean? It means we will emerge more risk-averse, unwilling to expose ourselves financially, determined to save and to ensure that, should there be a recurrence of such an instant, all-enveloping event, we’re prepared. Against this mood, bling and celebrity appear frivolous. They always were but now they really are.

Just as 9/11 made heroes of firefighters, and wars of soldiers, our icons in 2020 are frontline health workers. It no longer feels uncool to say you want to work in healthcare, you wish to help others.

Similarly, it’s not unfashionable any more to choose a job in government, for the state, for the body charged with trying to solve a problem such as this, that aims to ensure its citizens are protected – not least because it now affords a degree of security that the thousands losing their jobs because of corona would dearly crave.

My eldest son asked my father, 88, if it was “like this in the war, Grandad?” He replied that “well, we did not have the internet, mobile phones, television, central heating, food…”

In a sense, though, the question was rightly judged. This is not dissimilar. Never again will I be critical of their preparedness, their unwillingness, despite their happiness, to shake off an underlying, nagging anxiety. When pushed they would say “you never know what might happen, you should always guard against a rainy day”. We used to mock that rainy day – where is it, when is it coming? It’s here. Our parents were not so stupid after all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments