Fossil fuel giants make historic decision to write-down assets – but trillions still to go

Large investor groups commit to pressure other global oil companies to follow BP’s lead and write-down their bad fossil fuel assets, Ben Chu reports

Pressure is mounting on global oil companies to clean up their balance sheets to reflect a world finally acting to prevent runaway global warming in the wake of BP’s historic decision to write-down its fossil fuel assets.

The UK-headquartered oil giant took the decision to take the $17.5 bn (£14bn) accounting hit this week after judging that the future price of a barrel of oil will be considerably lower than it previously estimated.

This reflected a view from the company’s bosses that the coronavirus pandemic will accelerate the world’s transition to a low-carbon economy and that the price of oil is not returning to its pre-crisis levels.

“We’ve got a breakthrough. It totally vindicates what we’ve been saying,” said Natasha Landell-Mills of Sarasin & Partners, a UK asset manager that has been urging energy companies to recognise potential bad fossil fuel assets.

A host of asset management groups – including the $7 trillion (£5.6 trillion) investment giant BlackRock – are now urging other oil companies to follow BP’s lead in addressing their “stranded assets” – fossil fuel investments that will not pay off if the world succeeds in decarbonising energy generation in the coming decades and governments meet the 2015 Paris Agreement target of keeping planetary warming below 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels this century.

Investment companies collectively managing $40 trillion (£32 trillion) of assets have banded together in an initiative called Climate Action 100+ to pressure firms in which they invest to take serious action on climate change.

Bruce Duguid of the asset manager Federated Hermes, who co-led the initiative’s engagement with BP, said it would be applying similar pressure on other firms.

“We want to see others follow suit,” he told The Independent.

There could be many hundreds of billions of dollars of asset write-downs to come from other global oil companies in the months and years ahead as the reality of peak demand for oil becomes apparent and firms’ accounting teams are forced to respond.

If BP does it, it’s going to be hard for others to say that we won’t

Driving BP’s asset write-down was a revision in its internal future oil price forecast down from $70 (£56) a barrel to $55 (£43). That new estimate is well below the internal estimates being used by other European headquartered oil firms such as Spain’s Repsol, Italy’s Eni and France’s Total.

The US oil giants, including Exxon Mobil and Chevron, do not publish their own internal oil price forecasts used to value their assets, but analysts say there is no reason to believe they are more conservative than those of their European peers.

This implies that, if these firms were to do what BP has done, they too would need to announce vast asset write-downs.

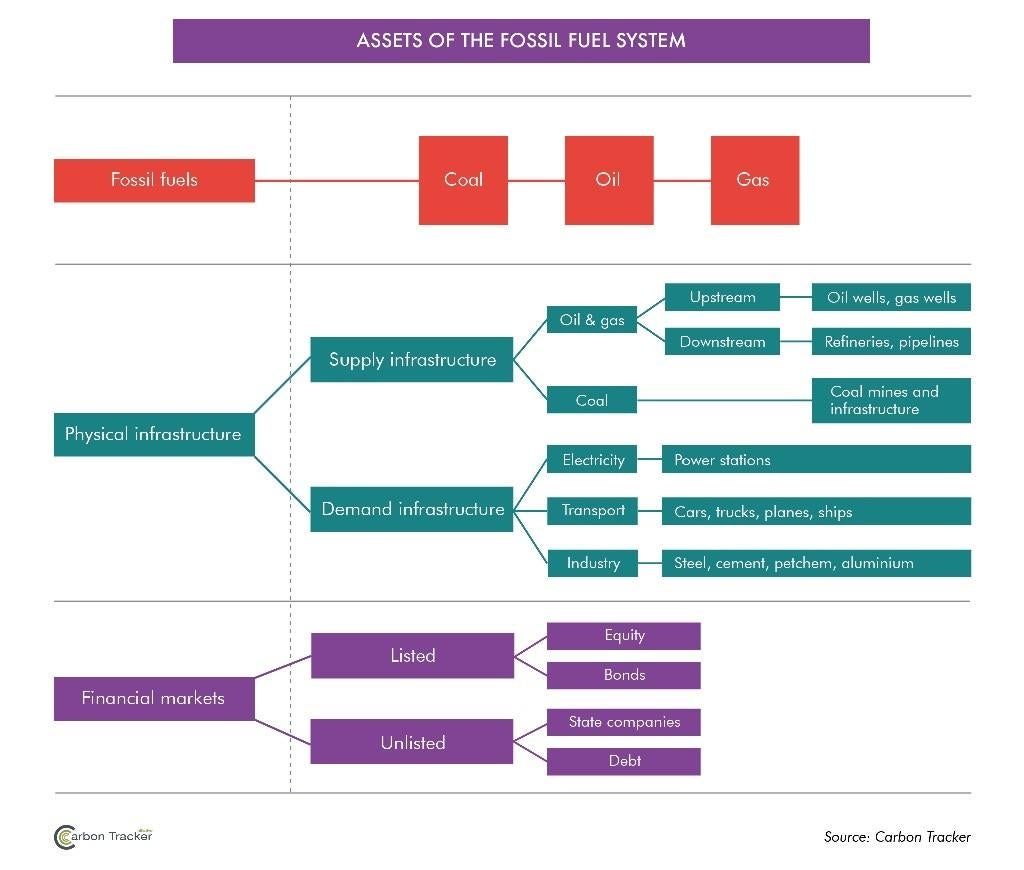

The vulnerable assets would be proven oil and gas reserves in the ground but also the industrial machinery required to extract them. Analysts put the world’s total fossil fuel wealth in the tens of trillions of dollars, with much of that held by petro-states such as Saudi Arabia and Russia.

The Carbon Tracker think tank estimates the value of fossil fuel industry supply infrastructure, such as oil wells and refineries, at another $10 trillion (£8 trillion).

$10tn

Estimated value of fossil fuel industry supply infrastructure, such as oil wells and refineries

While big oil companies such as BP have adopted the rhetoric of decarbonisation – often called “greenwashing” – in recent years their actions have told a different story, with these firms’ spending on low-carbon technologies such as wind and solar amounting for less than 1 per cent of their total investments.

Analysts say that financial pain of a coming wave of write-downs will create a powerful incentive for a genuine change in approach and a major investment shift into low-carbon projects.

“You need to move from greenwashing to strategy,” said Kingsmill Bond, an analyst at the Carbon Tracker think tank.

“If demand for oil was going to come back and it was just a question of batting off the annoying greens for a few years, greenwashing would be fine – and that’s what a lot of these guys clearly thought. But unfortunately for them, it’s a real issue.

The oil price hit a peak of $68 (£54) a barrel in January but collapsed in the subsequent months as the coronavirus pandemic plunged the world into recession, crushing industrial demand for oil. The price was pummelled further as Saudi Arabia flooded the world with additional supply after a bust-up with Russia in which the two oil-producing nations failed to agree on production cuts to support the market price.

The price of a barrel of Brent crude hit a low of $22 (£18) in April but has since recovered somewhat to $41 (£34).

Lockdowns and recessions have slashed the world economy’s demand for fossil fuels this year. Global CO2 emissions were over 5 per cent lower in the first three months of 2020 than in the same period in 2019, and the International Energy Agency (IEA) has estimated that global emissions for the full year could be 8 per cent lower than in 2019.

But the big question is what will happen to demand for fossil fuels as the world emerges from recession. BP’s chief executive, Bernard Looney, recently suggested that the shift to home working could be permanent and result in a secular fall in demand for fossil fuels for transport.

Others hope that the crisis will result in governments decarbonising faster.

“This whole Covid disaster is so significant because it means governments can have the ability to rethink the way they do things – it’s a natural break point,” said Mr Bond of Carbon Tacker.

“I am more optimistic because the coronavirus has probably brought forward the time of peak oil, so it will have a permanent effect on demand and therefore emissions,” said Mr Duguid of Federated Hermes.

“Companies are now having the foresight to build this into their assumptions and not expect a return to business as usual.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments