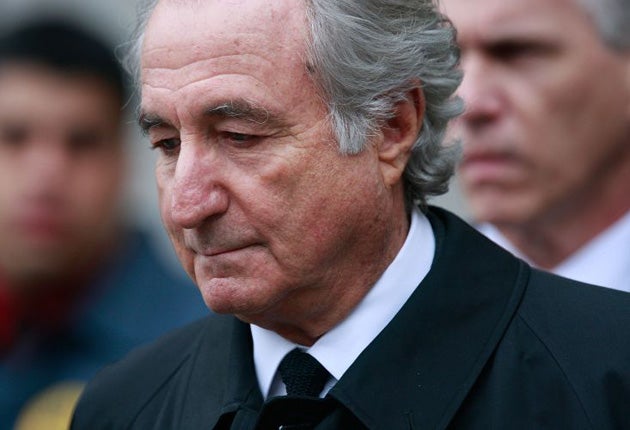

Bernie Madoff was proof that if something is too good to be true, it usually is

While we’re currently poring over Greensill’s demise, we should be looking for the next Greensills and Madoffs, firms that are of doing well but are similarly built on sand or fraud, writes Chris Blackhurst

The death of Bernie Madoff should draw to an end one of the most tarnished episodes in the recent history of finance.

Except it won’t. Madoff’s passing in a US jail where he was serving 150 years after pleading guilty in 2009 to running a giant “Ponzi” scheme – paying investors with new money coming in from clients, rather than from actual profits – serves as a sharp reminder of the failings of a system intended apparently to prevent such frauds.

Some $170bn flowed through the books of Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities, much of it via the London office, which played a pivotal role in the scam. Almost 5,000 investors lost more than $21bn. When his operation was closed down, less than $1bn remained.

Read More:

This wasn’t a crime that occurred overnight, it wasn’t a one-off event. His scheming lasted for at least two decades, possibly longer. In the end, after Lehman’s demise spooked the markets, Madoff ran out of road – he simply did not have enough new clients to turn to and new funds to access, in order to satisfy the old customers and to carry on living the lie.

Nevertheless, he’d had the most extraordinary run. Unknown and low profile outside investment, within it he was a hero – a fund manager seemingly possessed of the Midas touch, someone who could be counted on to always deliver a good, steady return.

In fact, all he did was decide how much profit he wanted to generate, then set about using historical share pricing data to construct the deceit that his firm had bought and sold at the prices necessary to produce that figure. Settlement documents were faked and client statements were rigged in order to prove the deception.

He managed it, too, by drawing potential customers in, by tapping them up, having a quiet word, letting them in on his little goldmine, making them feel privileged and chosen. They fell for the patter of well-mannered, quietly-spoken, assuring “Uncle Bernie” in their droves.

What Madoff highlighted was that so long as everything in the kingdom points upwards it’s fine. Only when the line dips are explanations required

The trickster maintained he did it by himself but that was preposterous – he had to have received assistance and plenty of it. Madoff spun his web year after year, and he was believed.

This is where the Madoff story should force many in the City, Wall Street and elsewhere, to take a long, hard look at themselves. He was living proof of the adage, often quoted on trading floors, that if something “is too good to be true it usually is”. Yet, virtually no one sought to question his consistently profitable performance.

Far from scrutinise, they fell over themselves to buy into his apparent success. The truth was that in many cases it was not their money – it belonged to their clients. Another well-worn phrase beloved of the investment community that springs to mind here is “other people’s money” or “OPM”. If it had been their hard-earned savings they were pumping in, they might have thought twice and conducted some due diligence on the apparent stock market genius. As it was, they did not care – all they did was charge fat management fees to their clients for their brilliance in picking Madoff.

When the business went down, one London fund manager I know was challenged by two UK clients as to why their money had gone into Madoff, why hadn’t checks been made? The fund manager replied that they’d moved the clients’ money along, to another investment manager, and it was that firm which had put their money with Madoff. “Don’t blame us,” they said. “Blame that firm, they were the ones who should have known.” The lack of remorse was astonishing, but all too typical. OPM, that’s what it was.

What Madoff highlighted was that so long as everything in the kingdom points upwards it’s fine. Only when the line dips are explanations required and the recourse begins.

How many times do we have to witness the same chain of events? We’re seeing it again, now with Greensill. When that finance company was doing well, everyone, in the City, government and media, could not get enough of it. Its performance turns, and bang, the whole lot implodes. While we’re currently poring over Greensill’s demise, we should be looking for the next Greensills and Madoffs, firms that are of doing well but are similarly built on sand or fraud.

In theory, we’re expected to rely on the accountants to probe the ledgers, to test the figures, to expose the foundations. Honestly, though, how often does that happen?

As for the other supposed brake, the supervisory authorities, they’re not up to the task – Madoff illustrated as much, and nothing has changed since to bolster confidence. The numbers and records they were being shown appeared sound – Madoff said so, his advisors said so, his clients even said so (they were willing him on, wishing him to succeed). What wasn’t to like?

Actually, some clients did suspect and chose to remain silent. This is another example of egregious banking behaviour cast under the spotlight by Madoff – of no one speaking out, for fear of upsetting the gravy train and afraid of being branded as someone who speaks out. The City and Wall Street, the banks, lawyers, accountants, insurers, PR advisers, the whole gamut of cheerleaders and enablers, do not appreciate those who blow the whistle. From the moment you start work in such places you are told to keep quiet, to not say anything out of turn. That means playing dumb as well. Bad news only pushes down a share price, knocks a reputation. Do you hear what I’m saying?

That was accompanied by the investment industry’s collective FOMO. The herd instinct told them to desire a part of Madoff, to join the party, be a member of the gang. To do otherwise would invite derision. “Are you serious, you turned down Bernie?”

Read More:

When he was challenged, and the interrogator could not be brushed off, Madoff told them they could keep their money. Even then, those who turned tail did not warn the rest – some did, but not enough and even then, their misgivings were largely ignored.

Madoff’s incredibly long sentence may have been intended, pour encourager. Alas, the case did not serve to encourage a systemic change in attitudes and wholesale reform. Without those, there will be more Madoffs, perhaps not with his gargantuan appetite but more, nonetheless. He may have gone but the flaws he so vividly exposed remain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments