Populists in the 1975 European referendum paved the way for Vote Leave’s Brexit victory

In the second of our five-part series on Britain’s often reluctant role on the European stage, Sean O'Grady examines how the losers of the In/Out vote 45 years ago bequeathed some useful lessons to 2016’s Leavers

As we’ve been reminded in recent weeks, a political campaign, or at least a bad one, can make a real difference to the outcome of a national vote. Lessons for such experiences can always be learnt, though not always are. It is rare, though, for a campaign to cast as long a shadow as the 1975 referendum on whether Britain should stay in the European Union. In many ways we are living still with the distant reverberations of its impact.

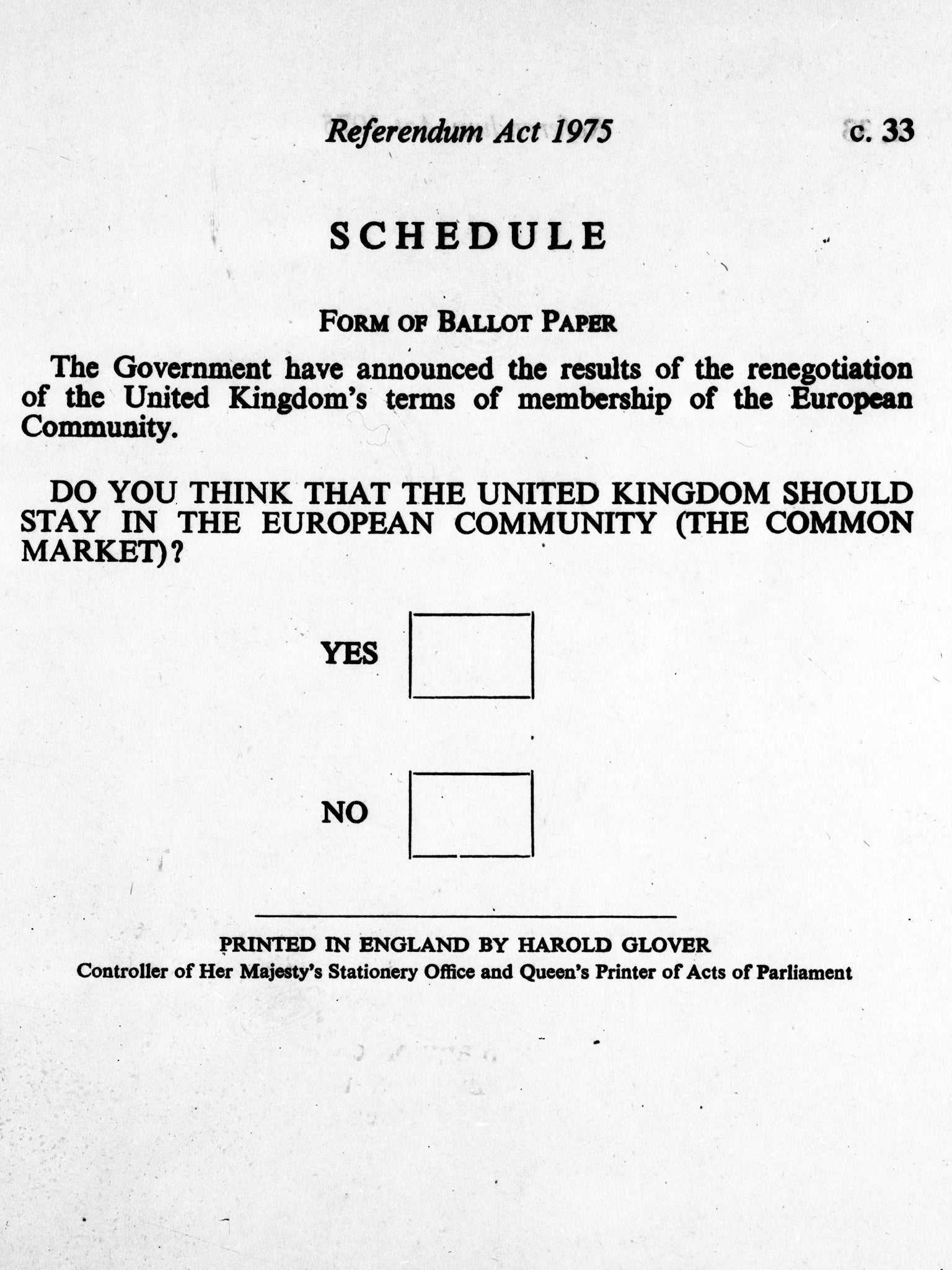

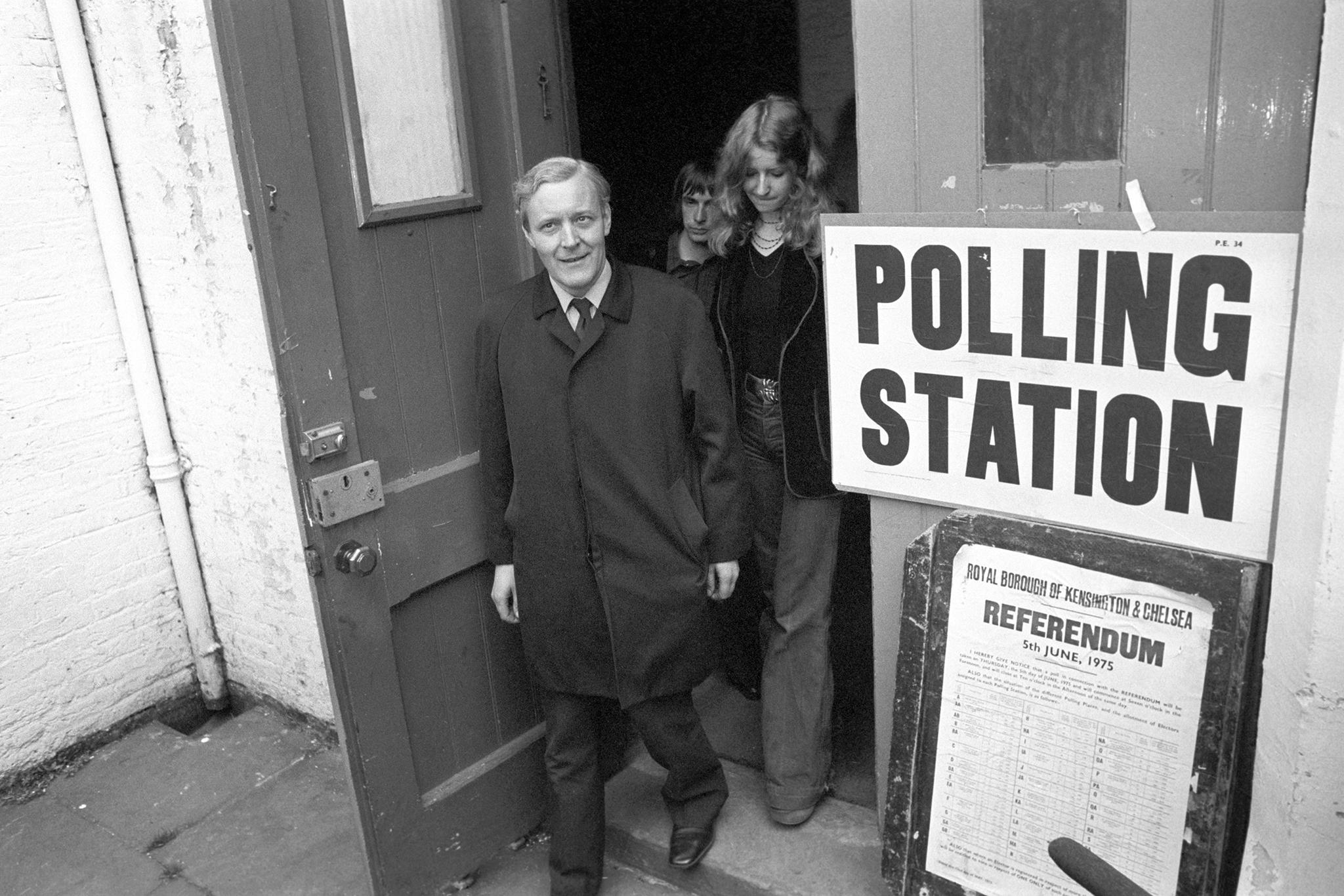

This was Britain’s first ever national referendum, and was thus a radical constitutional innovation – and, as we saw in 2016, a lasting one that sat uncomfortably with the UK’s traditions of parliamentary sovereignty. On Thursday 5 June 1975, a sunny but cool day for the time of year, some 25,903,194 (about 65 per cent of the electorate) came out to answer the following question, as set out on the ballot paper, with a Yes/No option:

“The Government has announced the results of the renegotiation of the United Kingdom’s terms of membership of the European Community.

Do you think that the United Kingdom should stay in the European Community (the Common Market)?”

When the votes were totted up, the Yes side won by about two to one. Every region or country of the UK voted to stay in, with the exception of the Shetlands and the Western Isles. The largest Yes vote was recorded in North Yorkshire, with 76.3 per cent in favour of what we would now call “remain”.

Although the verdict of the 1975 referendum stood for more than forty years, and although, looking back, it might seem obvious that the UK wasn’t about to jump out of the EU (then the European Community) after only two years of being in, at the time the success of the pro-EU campaign was against the long-term trend of public opinion. Almost every poll, for example, between 1967 and 1974 showed an element of public dissatisfaction with the European project. The 1975 referendum “should” have been one that the Out campaigners (“Leave” in 2016 terms) “should” have won. The reason why the Eurosceptics of 1975 did not and why the Leavers did win their famously narrow victory in 2016 have some striking parallels.

Indeed, it is not too much of an exaggeration to say that the lessons of 1975 were learned so well by those in charge in 2016 it helped to “get Brexit done” now.

Jason Farrell and Paul Goldsmith, for their lively account of Brexit, How to Lose a Referendum, interviewed Matthew Elliott, the chief executive of the official cross-party Vote Leave group.

As Farrell and Goldsmith explain: “Elliott recalled some research he had been doing long before the referendum, in 2012, for a speech he was due to give. He came across a cartoon that had been published on 24 March 1975 in the Evening Standard. It depicted the No campaign against EU membership from that time. People were on a march and at the front, Enoch Powell, Tony Benn and Michael Foot were under a banner reading ‘Get Britain Out’, while in the crowd of people there were placards saying National Front, Communist Party, Scottish Nationalists, Trotskyists, Anarchists, IRA, Orange Order. The tagline underneath was ‘Join the Professionals’ [an army recruiting slogan of the time]. Although it was published before the referendum, it was one of the best illustrations of why the 1975 campaign lost.

“Elliott saw the obvious message: ‘It was basically saying … they were a rag-tag bunch of people, dominated by extremists.’

“He knew that if a referendum was coming, the Out campaign would need mainstream players on board. For that, it needed an organisation that could cater for them. In his view, the worst-case scenario would be a Ukip-led purple revolution”.

And that, of course, is why Elliott and Dominic Cummings made sure that Nigel Farage was relegated to his own Leave.eu vehicle, and kept at a safe distance from Vote Leave and its more respectable public faces – Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and Gisela Stuart.

This sentiment very much echoes the thoughts of Roy Jenkins, one of the pro-Europe leaders in 1975. (He was later to become president of the European Commission, the only Briton to have held the post.) Jenkins remarked about the 1975 experience: “The people took the advice of people they were used to following.” Of course in 2016 they were less deferential and less inclined to follow the establishment, but the point about a reluctance to vote for obvious extremists still stood in 2016. A campaign led and run by Farage, Arron Banks and the other “bad boys of Brexit” might well have failed to cross the 50 per cent threshold.

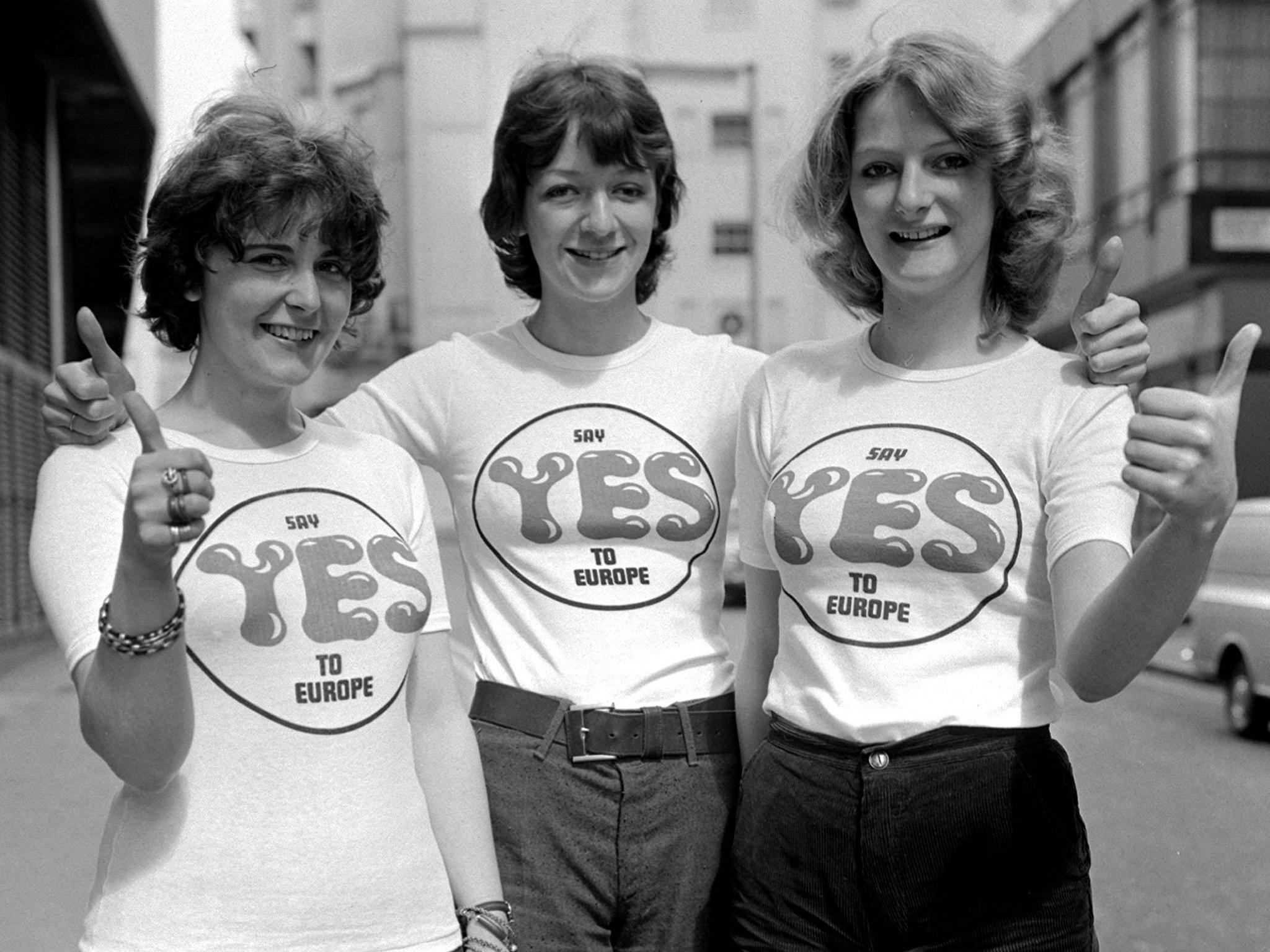

In 1975 the main party leaders – Harold Wilson, as Labour prime mister, and Margaret Thatcher, the newly elected Conservative leader, took something of a back seat in the campaigning. Instead, some of the country’s most popular political personalities – Jenkins, Shirley Williams, Jeremy Thorpe (the Liberal leader, before his downfall) and Willie Whitelaw all made the running, and ran a coordinated effort with some clear messages backed by strong research and a feel for public opinion.

Economic arguments were deployed, on broad principles, but not, as in the later “Project Fear”, excessively and with spurious detail. A mere 30 years after the end of the Second World War (a shorter time than the 1975 referendum is from us today) the notion of the European Community as a way of keeping the peace in Europe had a powerful resonance. The In campaign also made sure to “target” its ads for audiences in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland respectively, and had attractive messages for all classes. On the whole those who worked together across parties on the campaign enjoyed themselves.

In contrast, the Out campaign was a shambles, because of the bitter differences (away from Europe) that divided them. Enoch Powell, for example, used to sit through committee meetings in uncharacteristic “strange silence” as one witness put it; Tony Benn, a fine orator and energetic grassroots campaigner, failed to turn up to a single meeting. (Benn had previously, at the 1970 election, accused Powell in these terms: “The flag of racialism which has been hoisted in Wolverhampton is beginning to look like the one that fluttered 25 years ago over Dachau and Belsen.”)

Many Out campaigners refused to appear on platforms with one another, and their messaging was confused. They were also very short of money, compared to the pro-Europe gang. “Bennery” was regarded as an eccentric and lethal cocktail of mixed-up socialist economics and pacifism; “Powellism” was seen as a nationalistic, sovereignty obsessed, nakedly racist attempt to reverse the multicultural society and turn British subjects who happened to have brown skins into marginalised second-class citizens, unprotected against unfair discrimination. Both doctrines had their adherents, and both of these charismatic men had their fans; but they were not seen as mainstream or taken seriously by the bulk of the electorate. Polls showed them both to be extraordinarily unpopular figures, who toxified the Out cause. The only one who outdid them was the DUP leader Ian Paisley, who described the Common Market as the “Kingdom of the anti-Christ”.

This is no time for Britain to be leaving a Christmas club, let alone the Common Market

Despite the fact that they were both “on the same side”, the pro-EU campaign in 1975 also had a much better set of arguments to present than the Remainers of 2016. For a start, although both prime ministers, Wilson in 1975 and David Cameron in 2016, had been “renegotiating” Britain’s terms of membership in Europe, Wilson made a better job of spinning his. He avoided asking for treaty changes (which would be cumbersome to introduce and ratify) and admitted that he hadn’t got everything that he wanted, but sufficient to recommend a “Yes” vote. He won minor but useful concessions, and did not oversell them. Cameron was the opposite, trying to argue that his cosmetic alterations were a much bigger deal than they were, and he encountered some vicious ridicule for his efforts. The unpopularity of his government attached itself too readily to the Remain campaign, with the disliked “austerity” chancellor George Osborne in a prominent role. His Seventies predecessor Denis Healey, a Euro-agnostic, kept a lower profile for the 1975 contest.

In 2016, too, the country was less likely to be terrified by “Project Fear”. Despite some disgruntlement, stagnant wages and many areas feeling “left behind”, there was no sense of impending doom of crisis. In 1975 the background was very different.

Until the oil price shock of 1973, the then six members of the European Community – France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands – had seen decades of cracking growth in GDP and in living standards, overtaking Britain and leaving the UK to be pitied as the strike-ridden “sick man of Europe”. Inflation in the summer of 1975 hit an annual rate of 27 per cent. Prices would jump by 4 per cent in a single month alone – about two years’ worth of inflation in the 2010s. “Stagflation” was a thing – stagnant growth with near hyperinflation and record unemployment. With corporate collapses, strikes and terrorism, there was a sense that Britain was becoming “ungovernable”. Europe was not a popular cause; but it was seen as one of the few options the country had to try and repair itself. As one of the grandees of the day, Churchill’s son-in-law Christopher Soames, said: “This is no time for Britain to be leaving a Christmas club, let alone the Common Market”.

In 2016, by contrast, the European Union was seen as part of the problem rather than a part of the solution. All the images and stories that emerged from the continent in the previous few years – again, rightly or wrongly – gave the impression of a failed, chaotic, sclerotic project: pitiful refugees dying in an attempt to cross the Mediterranean and the English Channel; dangerous, squalid camps such as “the Jungle” at Calais; riots in Athens; banks collapsing; bailouts costing EU taxpayers billions; youth unemployment hitting obscene levels; the euro single currency itself close to break-up; the rise of the far right and far left even in places such as Sweden and Germany; and Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece and Ireland going bust. Europe was no longer the dynamic place it had been in the first couple of decades since the EEC’s inception in 1957.

The sovereignty debate – ‘take back control’ – was an easier one for the Leave side to win in 2016 than in 1975

The fact is that the 1975 “anti-marketeers” had the opportunity to get Britain out in what a leftist might call pre-revolutionary conditions, but they failed to capitalise on the grim economic situation, failed to tap into that emotion of national despair, failed to work together, and failed to offer a coherent alternative. The left wanted a siege economy with import controls and huge state intervention (what later re-emerged as Corbynism); the right preferred monetarism and what would come to be known as Thatcherism. Neither was particularly appealing to the average “moderate” centrist British voter of the 1970s, fed up with strife and strikes.

Nor, of course, was the 1975 Out campaign able to make much of immigration as an issue connected with the EU. The issue for Britain in the Seventies was much more one of net migration – the “brain drain” – as many gave up and moved abroad to make a life for themselves and their families. There was no equivalent of the volume for east Europeans that arrived in Britain after about 2005.

In terms of sovereignty, the pro-Europeans of 1975 also had the better of things. It was still true in those days that the UK would have a theoretical veto on any issue that clashed with its vital interests. The rules of the club were often perceived to be rigged against Britain – with higher food prices and substantial sums sent to Brussels to pay for the Common Agricultural Policy – but if a new proposal came forward that a British minister didn’t like, then they could make their displeasure known and have it amended or withdrawn (the veto was thus rarely invoked).

In 2016, after the 1986 Single European Act and the introduction for qualified majority voting, the UK could only block a measure if it formed a coalition with other like-minded countries – the likes of the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark, for example. So the sovereignty debate – “take back control” – was an easier one for the Leave side to win in 2016 than in 1975.

However what was curiously absent from the 2016 debate was any suggestion that sovereignty need not be absolute, and could be shred or “pooled” to extend British influence across the EU. Heath put it well in a TV show at the time, when he said that sovereignty wasn’t something to be hoarded in a cellar where you go down from time to time to see if it’s still there, but to be used to further widen British interests. In doing so he managed, at that time, to prevail over the Powellite view that sovereignty was a rather mystical concept embodied in the British parliament, and which no British parliament can abnegate on any permanent basis to some foreign power. The potency of that idea was to return in the 2010s.

Many at the time disliked the referendum, and, when it was over, Wilson promised that it would not be used again, though of course he could not stop it

The 1975 referendum, though, did not settle the European issue – any more than the 2016 one did. In the words of the definitive psephological study of the time, the 67.2 per cent to 32.8 per cent split was “unequivocal but it was also unenthusiastic”. Indeed, Europe was to be mostly unloved for the next four decades. By 1983 Labour was back to promising to leave Europe – without a referendum, and by the 1990s, Conservative Euroscepticism was established as a fighting force. What was more permanent was the notion of a referendum to settle major issues cutting across party lines, particular Europe.

Referendums on Britain joining the euro single currency were promised by John Major and Tony Blair before the 1997 general election, followed by a pledge for an In/Out EU referendum made by Nick Clegg for the Liberal Democrats. The Referendum Party – a Eurosceptic organisation fronted by Sir James Goldsmith – fought the 1997 election, and Ukip started to make its presence felt, with Nigel Farage the loudest voice calling for a plebiscite on EU membership. Ukip came second in the 2009 European parliament elections, and won in 2014. Each new EU treaty – Maastricht, Nice, Lisbon – prompted demands for a referendum (which did happen in other EU states). The Tories under Cameron even legislated in 2011 for a “referendum lock” on new treaty changes.

The referendum was a constitutional novelty almost entirely the work of Tony Benn. He had been arguing for it in the spirit of popular “participation” since the late 1960s, when he was, for a time, a technocratic centrist and in favour of joining Europe. It was also a device that was supposed to help keep the Labour Party united, because in those days it was the left that was more bitterly divided on Europe than the Conservatives. Through persistence, Benn managed to get the Labour Party to adopt the referendum pledge in its 1974 election manifesto, with the promise to deliver it within a year of winning power, which they did.

Many at the time disliked the referendum, and, when it was over, Wilson promised that it would not be used again, though of course he could not stop it. The referendum indeed has become much more a favourite fall-back for a politician in a tight corner, and has been used frequently since 1975, including in Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and the English regions and cities, such as for directly-elected mayors). On a national level it was wheeled out again for the 2011 referendum on electoral reform, as well as the 2016 Brexit referendum.

Despite a country heartily tired of Brexit, it is inconceivable that any attempt to get Britain back into the EU in future would be done without recourse to a referendum to signal popular approval. Contrast that with the first attempt at getting the UK into the European Community, in 1961, which was not even mentioned in the previous Conservative manifesto. Heath, in 1973, took Britain in after a series of precarious votes in the Commons, and with no popular expression of approval.

The referendum, then, is here to stay, and Britain has opted to “take back control” and rediscover the potential, and limits, of national sovereignty, including putting some stringent limits on immigration. Thus the 2016 referendum result, and its long, traumatic aftermath, might well be seen to be the final posthumous victory of Bennery and Powellism. At the peak of their powers in 1975, Benn and Powell, both in their different ways populists, lost; in 2016, when their memories were already faded, their populist ideas, at last, won. They are the godfathers of Boris Johnson.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments