The Iceman Cometh: What I discovered when I learnt to breathe like Wim Hof

Chronic back pain can be debilitating but something as simple as deep breathing can be life-changing. Christine Manby takes a deep breath in

Brexit did my back in. As the news broke on 28 August that Boris was going to prorogue Parliament, I felt muscles I didn’t even know I had contract with anxiety. Watching the subsequent row unfold in the news and on social media, I hunched over my laptop for much too long and when I finally stood up, wham. I was struck double by the “Hexenschuss”, the witch’s shot, as the Germans call it.

Knowing that if I sat back down, I’d never get up again, I leaned heavily against the kitchen counter to call my friend and fellow author Michael Maisey, who was due to tell me all about his experiences with the Wim Hof Method. Michael, who spent most of his teenage years in Feltham Young Offenders Institute, becoming a heroin addict and alcoholic along the way, is almost 12 years sober. The Wim Hof Method is part of the arsenal of wellness techniques he uses to stay that way.

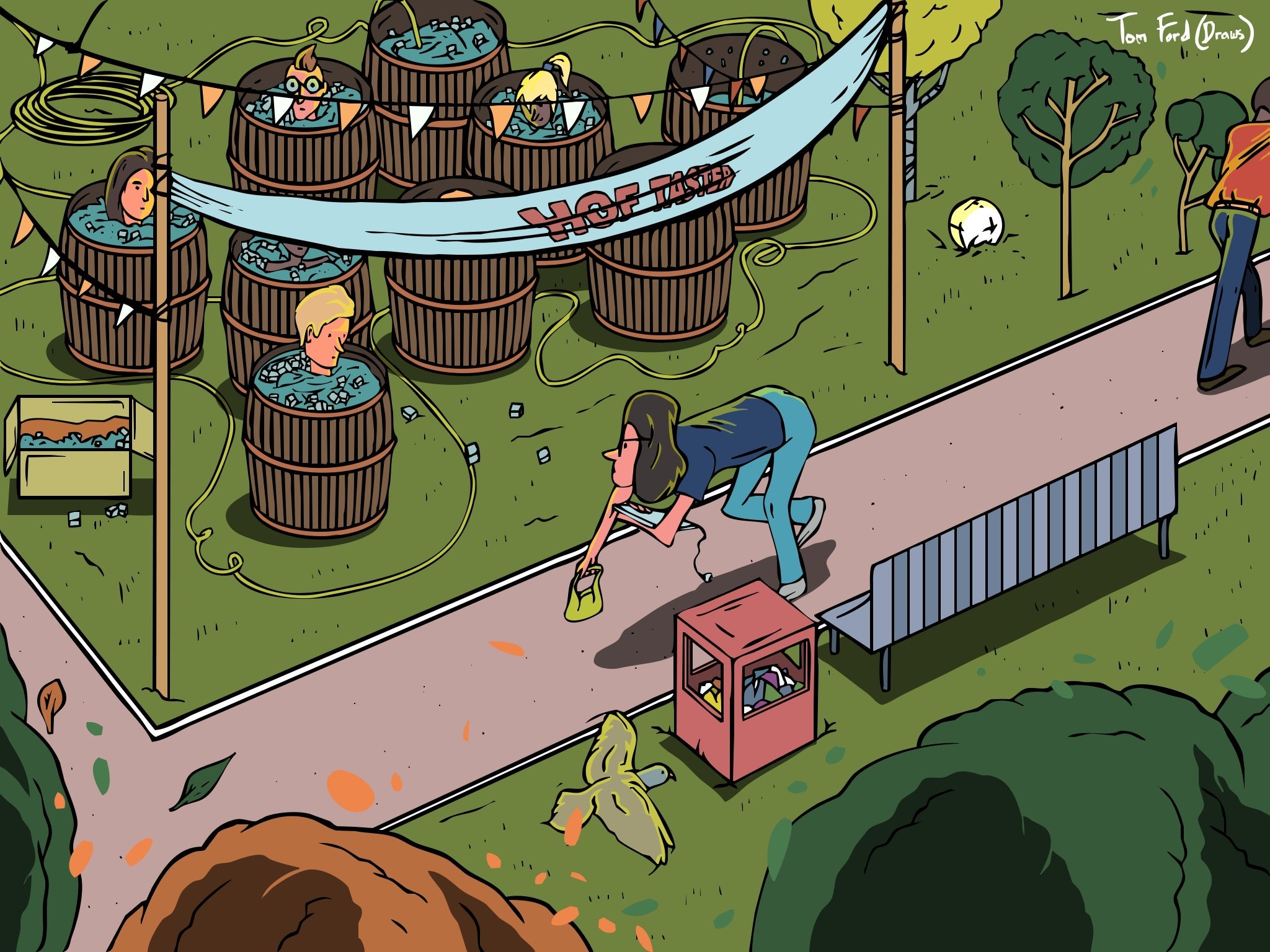

Wim Hof, also known as The Iceman, is a Dutch athlete. His nickname is apt, if unoriginal. He’s set records for sitting in ice and for swimming underneath it. In 2000, he swam 57.5 metres, setting a Guinness World Record. He still holds the world record for a barefoot half-marathon on snow. He once climbed to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro wearing only shorts. He claims that his feats of icy endurance are down to his eponymous Method, which combines breathing techniques and meditation with frequent exposure to the cold. His website is full of video clips of happy people sitting in giant ice buckets.

Watching Hof on YouTube, it’s hard to take him seriously. He’s like a spoof of a hippy with his long beard and straggly grey hair and there’s always the hint of suppressed laughter in his Austin Powers “smoke and a pancake” accent. His patent breathing technique looks to me at first glance like the hyperventilating my school friends and I would practice in an attempt to fake a faint before a French test.

As for the ice-bath stuff? The word that sprang to mind on that front was “nutter” even though just the previous evening, on a stifling 30-degree night in London, I would have paid a tenner to stick my feet in.

The claims Hof makes for his method are extraordinary. It isn’t only for improving your performance at insane sports. It can help improve the way you sleep. It can reduce stress. It can boost your immune system. In one testimonial, Matt, a Hof devotee from Devon, claims that the Method cured his Lichen Planopilaris – an autoimmune disease that affects the skin – enabling him to stop taking the prescription drugs that had left him racked with charming side-effects such as coughing up blood. Matt also credits WHM with helping him to maintain his mental health.

My friend Michael recognises Matt’s experience. He came across WHM via a documentary he found on line. Like me, Michael’s first thought was that Wim Hof must be a freak of nature but, no stranger to physical challenge himself, he decided to give the breathing technique a punt anyway. He first tried to teach himself by watching YouTube videos. Later, he attended a course taught by Wim Hof himself, where he took the dreaded ice bath. Since then, Michael has been practising the breathing technique and taking cold showers almost every day for two years and says that he hasn’t been ill in all that time. He also credits WHM with helping him to stay calm and focussed when, just as he was launching his first book, Young Offender, he learned that his father had died. “It’s like an anti-depressant for me,” he says of the breathing technique in particular.

Now Michael introduces others to the Method – including the ice bath – at the Devon-based men’s retreats he runs several times a year. Just hearing about it made me want to hyperventilate. The combination of holding one’s breath and jumping into freezing water could never seem like anything more than torture to me.

Yet, Michael persuaded me to give the breathing technique a go. He explained how it works. Put simply, you build up the concentration of oxygen in your blood by breathing in deeply – “to 100% capacity” – then letting the breath out – “but not all the way” – 30 or 40 times before you breathe out and then pause in breathing for as long as feels comfortable. Then you breathe in naturally and hold that in breath for 10 seconds before starting the whole sequence again.

It sounded… confusing. I decided to let Hof guide me through the sequence himself. Michael sent me the link to Hof’s introductory video. I joined Hof, virtually, cross-legged on the floor – getting cross-legged took some doing – and began. Belly, chest, head. We breathe with all of them apparently. I couldn’t seem to get my breath above my neck or below my belt. My back was screaming for attention. About three minutes into the video, Hof mentioned that the breathing exercise is best done on an empty stomach. I’d just had some toast and a bucket of tea. No wonder I felt weird. I gave up.

Later in the afternoon, I tried again. It was sort of by accident. I’d gone upstairs to find a book. I was still locked into a 90-degree angle by the Hexenschuss. I sat down on the floor. Then I lay down, hoping for some relief from the pain. I pulled out my phone and scrolled to the video link Michael had sent me. Wim Hof’s voice, with its hint of chuckle, started up. I decided I’d give it one more go.

“Fully in. Letting go. Not fully out but fully in…”

I breathed along with the master 30 times. After the first round, I held my breath for one minute. At the end of the second round, I managed one minute, 10 seconds. At the end of the third round, I was astonished to see that I’d managed a minute and a half. But it wasn’t just that I’d been able to improve my breath-holding by 50 per cent in the space of 10 minutes, I was certain I could feel a difference in my body. I definitely felt a tingling sensation down the back of my legs. I wasn’t sure whether it was a good thing.

Tentatively, I began to sit up, bending my knees and holding on to the back of my thighs as I rolled my upper body from the floor. Prior to the exercise, I’d been unable to get up from a prone position without first rolling on to my side. Now I could sit straight up. I tried a couple of full Pilates-style roll ups for good measure. I stood up. I leaned forward to touch my toes and didn’t get stuck there. I couldn’t believe it. My back was fine. Was it all thanks to the Hof?

Wim Hof’s Method has been put to the test by people far more rigorous than me. Over the years Hof’s made some big claims about reducing the symptoms of MS and Parkinson’s Disease and even curing cancer that certainly require close scrutiny. However, journalist Scott Carney, who set out to debunk Hof’s theories in his book What Doesn’t Kill Us, ended up becoming a devotee himself. And in 2011, the University Medical Centre St Radboud in Nijmegen ran an experiment, the results of which were published in Nature, which appeared to show that Hof and his followers were able to harness the breath to voluntarily influence the autonomic nervous system.

As I write this, I am still astonished by the effect Wim Hof’s breathing technique seems to have had on my back. When I felt it go, I was expecting the usual: days of increasing pain followed by an expensive visit to the physio. To lie down on the floor in agony and get up again after 10 minutes of heavy breathing, feeling ready if not to run a marathon over ice then at least to walk to the supermarket without wincing, felt like a blinking miracle. I’m too flabbergasted to think of anything more to say other than “try it”. Whatever’s going on, maybe taking a deep breath and holding it Wim Hof-style could make you feel better. For now though, his ice bath can wait.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments